Acts of the Apostles 19

In Search of Authentic Discipleship

Works of art by Angu Walters, Norman Lewis, Pieter Coecke van Aelst the Elder and Willem de Pannemaker

Norman Lewis

Ritual, 1962, Oil on canvas, 130.2 x 161.9 cm, Private Collection; ©️ Estate of Norman Lewis; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

Ritual and Risk

Commentary by Rebecca Dean

Norman Lewis was a twentieth-century American artist and political activist. A contributor to the movement known as Abstract Expressionism, Lewis pushed the boundaries of its style, adding discernible human figures into otherwise abstract works, and drawing his political concerns into an artistic movement that aspired to locate itself above such matters (Fine 2015: 80).

While at times Lewis explicitly denied the political nature of his work, many of the paintings that he produced would seem to suggest otherwise. Their depictions of hooded figures and religious processions are redolent both of the meetings of the Ku Klux Klan and of the freedom marches of the American Civil Rights movement.

It is the ambiguity in the depiction of these gatherings that characterizes much of Lewis’s work, and Ritual is no exception to this. The group of small human figures form a crescent or bowl shape, which reviewer Daniel Gauss has likened to cupped hands (2016). There are hints of movement and flashes of bright colour, yet much is hidden in the inviting layers of deep blue. What lies at the heart of this gathering? What is its purpose? The intentions of the group are uncomfortably difficult to discern.

This painting captures something of the power, the allure, and the risk of human engagement in religious activity, and this is an important thread within the narrative of Acts. In chapter 19, we are presented with two dangers in particular: the use of the name of Jesus in an attempted exorcism—a ritual that goes wrong and leaves the exorcists wounded and humiliated (vv.13–16)—and the vulnerability of the Christian missionaries at the hands of the crowd in Ephesus. They drag Paul’s companions to the theatre, shouting and chanting in anger at the perceived slight on their goddess and their way of life (vv.28–29).

It is within this risky context that the Holy Spirit moves in Acts.

References

Gauss, Daniel. 2016. ‘Norman Lewis Retrospective, 20 December 2016’, www.meer.com [accessed 8 April 2024]

Fine, Ruth. 2015. ‘The Spiritual in the Material’, in Procession: The Art of Norman Lewis ed. by Ruth Fine (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts), pp.19–104

Designed by Pieter Coecke van Aelst the Elder, possibly woven by Willem de Pannemaker

Three Episodes in the Life of Saint Paul, from the series The Story of Saint Paul, Second third of 16th century, Tapestry, 405 x 686 cm, The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Charles Potter Kling Fund, 65.596, Photograph ©️ 2023 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Serving God or Serving Self?

Commentary by Rebecca Dean

This work was commissioned by Henry VIII in the 1530s, and is the only surviving tapestry from a set of nine designed by Flemish artist Pieter Coecke van Aelst. It is roughly twenty feet long and twelve feet high, and uses metal wrapped threads, wool, and silk within the design.

The work depicts three scenes from Paul’s ministry in Ephesus, as described in Acts 19 and 20: the laying of hands upon the disciples in Ephesus (top left), the miraculous revival of Eutychus (top right) and the burning of the magic books (centre).

The delivery of the Life of St Paul tapestries in 1538–39 coincided with the dissolution of the English monasteries. This entailed the forced sale of religious properties and land, and the destruction of monastic libraries and manuscripts, as well as the execution of non-compliant monks and nuns. The choice of subject matter for these tapestries was likely to have been highly significant. It was perhaps intended to align the events of the English Reformation with the actions of Paul in Ephesus, delivering ‘correct’ Christian teaching and overseeing the destruction of heretical or allegedly irreligious texts.

Such destruction is immediately visible within the tapestry, with the smoke from the pile of burning books dominating much of the upper section of the piece and blocking some of the human figures from full view. While the precise nature of these books and their possible magical content is debated by scholars, their monetary value is underlined within the Acts narrative (19:19).

The key point, however, is that the people of Ephesus were voluntarily choosing to destroy their own possessions, not forcibly destroying texts belonging to others, a nuance that appears to have been rather overlooked during the Reformation.

References

Cleland, Elizabeth A. H. 2014. Grand Design: Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Keener, Craig S. 2014. Acts: An Exegetical Commentary, vol 3 (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic)

Shauf, Scott. 2012. ‘Theology as History, History as Theology: Paul in Ephesus in Acts 19’, in Theology as History, History as Theology (Berlin: De Gruyter)

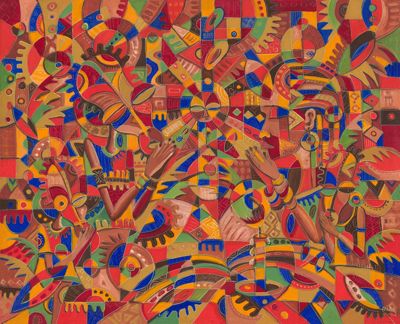

Angu Walters

The Evening Prayer II, 21st century, Oil on canvas, 100 x 78 cm, Collection of the artist; Courtesy of Angu Walters, Cameroon

A Living and Embodied Faith

Commentary by Rebecca Dean

The Evening Prayer II is an oil painting by Cameroonian artist Angu Walters. His studio is situated in the north-western city of Bamenda, which has been the location of violent civil war since 2017. While the harsh realities of this conflict have doubtless influenced him, his paintings, with their vibrant use of surrealism and caricature, tend to focus upon music, family life, and village scenes.

This focus on community—the corporate and the collective—emerges gradually from the abstract imagery of the painting. As one’s focus sharpens, the human figures become visible, with echoes of the shapes and tones of their faces and hands found throughout the rest of the work. The traditional prayer pose of the two central figures is interrupted by the single open eye of the smaller figure on the left, while the circular face in the middle, simultaneously both background and central image, radiates a halo of colours across the rest of the painting.

Are all of these faces engaged in prayer? Who or what else might be found within the shapes?

This focus on human bodies and body parts—clearly delineated and yet also interconnected—resonates with the embodied storytelling of Acts 19. Paul’s touching of the disciples with his hands brings the outpouring of the Spirit, which is in turn expressed through the tongues of the new believers (v.6). Paul’s skin somehow imparts healing power to inanimate objects (v.12), and the other itinerant Jewish exorcists are left naked after their failed attempt to cast out a demon (v.16). Sight, hearing, and touch feature in the words of Demetrius the silversmith (v.26) and as the chapter unfolds, we see not just individual bodies but the ‘citizen body’ in action (Brown 1992: 84–85).

This artwork can help to remind us that the story of Acts is one that is rooted in authentic human experiences of the living God.

References

Brown, Peter. 1992. Power and Persuasion in Late Antiquity: Towards a Christian Empire (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press)

Walters, Angu. ‘About Cameroon African Artist Angu Walters’, available at https://www.artcameroon.com/about-angu-walters/ [accessed 8 April 2024]

Norman Lewis :

Ritual, 1962 , Oil on canvas

Designed by Pieter Coecke van Aelst the Elder, possibly woven by Willem de Pannemaker :

Three Episodes in the Life of Saint Paul, from the series The Story of Saint Paul, Second third of 16th century , Tapestry

Angu Walters :

The Evening Prayer II, 21st century , Oil on canvas

‘Jesus I Know and Paul I Know. But Who Are You?’

Comparative commentary by Rebecca Dean

Acts 19 recounts Paul’s missionary adventures in and around Ephesus. A series of short, self-contained stories are linked together throughout this chapter. They are geographically connected, but they also share some common themes—chiefly, perhaps, that of authentic discipleship.

The section begins with Paul’s discovery of a group of twelve disciples who have only heard part of the Christian story: they have taken on board John the Baptist’s call to repentance but have not yet received the life-changing gift of the Holy Spirit. A little later, we read about seven exorcists who also think they have understood the Christian message and who attempt to use the name of Jesus to cast out an evil spirit. They learn the hard way that their understanding was only partial. As Willie James Jennings writes, ‘[T]hey discerned power instead of presence and did not sense the ecology of touch and relationship that moved in and through Paul and these disciples’ (2017: 186).

The embodied, relational faith depicted in the Acts of the Apostles can be easy to overlook, but it is this idea that is highlighted in Angu Walters’ painting The Evening Prayer II. This lively image also captures something of the dynamism of Acts 19. The chapter is set in the bustling city of Ephesus, famous for its temple dedicated to the goddess Artemis (the Roman goddess Diana), which was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. The temple functioned as a financial centre where people could obtain loans and deposit money, with its priests functioning as protectors of this wealth (Brinks 2009: 782). Worship, wealth, and social affiliations are deeply entangled within such spaces, and authentic religious devotion must be carefully discerned. However, authentic faith is not confined to ‘set apart’ spaces, as can be seen from Paul’s relocation from the synagogue to a public lecture hall belonging to the interestingly named Tyrannus (‘tyrant’) (Acts 19:9). The Christian God is at work, right in the midst of things.

The final third of Acts 19 is focused upon the discord between the Christian missionaries, led by Paul the tentmaker (see Acts 18:3), and the Ephesian devotees of Artemis, headed up by Demetrius the silversmith. Here are two artisans, both utilizing their skills in the service of their religion. Yet Demetrius is presented as being primarily concerned with the protection of his own income (19:25), while Paul’s generous and selfless service of the living God is underscored (vv.21, 30).

Consideration of the Pieter Coecke van Aelst tapestry foregrounds these questions of motive. While the vibrancy of this object makes an interesting contrast with the usually ‘polite’ and ‘tame’ biblical tapestries of the era (Alberge 2018), it is its possible symbolism within the context of the English Reformation that has generated the most discussion. The events of this period raise serious questions about censorship, religious freedom, and the use and abuse of religious authority, and as such the tapestry represents a challenging lens through which the biblical passage can be re-examined.

With its assertion of the superiority of Christianity over the religion of the Ephesian natives and its apparent celebration of the politically and historically complex act of book burning, this chapter does not always make comfortable reading. This discomfort may be compounded further by the mention of items of clothing that heal the sick (vv.12–13) and of evil spirits and exorcism attempts (vv.13–16). There is much in this account that may seem strange to many contemporary readers.

This sense of discomfort and uncertainty is profoundly captured in the painting by Norman Lewis. His depictions of ritual and procession have often confounded interpreters because of the ambiguity and even ambivalence that can be found within them. Art historian Ann Gibson suggests that such ambiguity should not be seen as a problem but rather as a ‘purposeful theme’ and a ‘strategy’ in Lewis’s negotiation of complex layers of meaning (1998: 41).

These are sentiments that may also serve as a helpful guide to readers of Acts. If we are able to sit with the questions and the emotions that this chapter generates, we may find a portrayal of authentic discipleship that is far richer and more nuanced than many interpreters have allowed.

References

Alberge, Dalya. 2018. ‘Lost Henry VIII Tapestry Rediscovered in Spain to Go on Display for First Time, 22 September 2018, www.telegraph.co.uk

Brinks, C. L. 2009. ‘“Great Is Artemis of the Ephesians”: Acts 19:23–41 in Light of Goddess Worship in Ephesus’, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 71.4: 776–94

Gibson, Ann Eden. 1998. ‘Diaspora and Ritual: Norman Lewis’s Civil Rights Paintings’, Third Text 13.45: 29–44

Jennings, Willie James. 2017. Acts: A Theological Commentary on the Bible (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press)

Commentaries by Rebecca Dean