Leviticus 24

Shelomith Bat Dibri: Making A Woman’s Legacy

Barbara Hepworth

Mother and Child, 1934, Cumberland alabaster on marble base, 23 x 45.5 x 18.9 cm, Tate; Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1993, T06676, ©️ Bowness; Image: ©️ Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

The (Im)Possibility of Separation

Commentary by Xiao Situ

With its undulating contours and natural materials, Barbara Hepworth’s semi-abstract sculpture suggests bones or other organic matter. Knowing its title, Mother and Child, however, may lead the viewer to decipher the work as more specifically human. Called Mother and Child, the work resembles a woman lying on her side with her right elbow anchored on the marble base and her knees bent upwards. She reaches out her left arm to cradle a baby on her lap. We can view the central hole in the composition not only as the negative space beneath the mother’s raised arm, but also the space within her body from which the infant emerged and which it has now outgrown. (Gale and Stephens 1999: 48).

Other aspects of the sculpture also hint at the parent–child relationship. While Mother and Child may at first appear to be a single alabaster mass resting on a plinth, it is actually composed of two separate pieces of stone: the larger horizontal body of the mother, and the smaller flatter body of the baby. It would, in principle, be possible for both the mother and child to exist independently and be displayed as two separate works. Exhibited alone, we might consider the woman’s pose as one of relaxation rather than caregiving. Without the stabilizing surround of the mother stone, however, the baby pebble must be laid flat on a horizontal surface, suggesting vulnerability and an earlier stage of infancy.

The story of Shelomith bat Dibri and her son raises comparable questions about the possibility of independence and autonomy between a mother–child pair. The inclusion of Shelomith’s name in Leviticus (a book about purity rules and ritual regulations) is based upon her maternal relationship to a man convicted of misconduct. Without her guilt by association, Shelomith might never have been included in the text at all. At the same time, the man’s misdeed might never have been written down were it not for his mother’s Israelite lineage. He is half-Egyptian, so it is his mother’s background that qualifies him to live among the Israelites.

The inclusion of Shelomith and her son in Leviticus is based on their inextricable tie to each other’s identities and actions. While the circumstances that led them to be written down in Israel’s history is cast as negative, the mere presence of these two figures in the book nevertheless preserves their memory in the heart of the Torah.

References

Gale, Matthew, and Chris Stephens. 1999. Barbara Hepworth: Works in the Tate Gallery Collection and the Barbara Hepworth Museum St Ives (London: Tate Gallery)

Julia Rooney

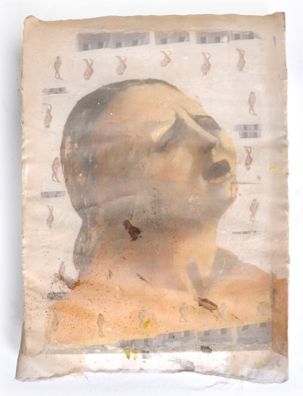

Eve Alone, 2017, Oil pant and photo collage on plaster, with chiffon overlay, 33.02 x 43.18 cm, Collection of artist ?; ©️ Julia Rooney; Image courtesy Julia Rooney and Yale Divinity School

She, Herself

Commentary by Xiao Situ

In Eve Alone, Julia Rooney reproduces the face of Eve from Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, a Renaissance fresco in the Brancacci Chapel of Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence. Rooney’s version leaves out Adam, the angel, and the landscape. Instead, the work is all about Eve, featuring her face painted on a rectangle of plaster. Tiny images of Eve’s body are scattered along the perimeter, interspersed by architectural elements that evoke the moulding above the gate of Eden in Masaccio’s fresco. The addition of a layer of translucent fabric visually softens the hardness of the plaster and adds an aura of mystery and delicacy to Eve’s face.

Taken out of context, some might interpret Eve’s facial expression not exclusively as despair, but perhaps as ecstasy. In Rooney’s own words, Eve Alone ‘is a meditation on the multivalence of Eve’ (Rooney 2018). The work ruminates on Eve’s complexity as an individual apart from the context of God, Adam, the Fall, and the Expulsion.

Although Shelomith bat Dibri is the only named woman in Leviticus and thus visible within Israel’s chronicles, she appears in the text in terms of her relationship to men. From the three verses in which her name appears (24:10–12), we can glean the following information: Shelomith was an Israelite woman. Her father was Dibri from the tribe of Dan. She bore a son with an Egyptian man. Her son got into a fight with an Israelite man in the Sinai camp, cursed God’s name, and was thus brought before Moses and put into custody.

In Leviticus as well as in canonical rabbinical texts, Shelomith is known primarily as the mother of an accused and imprisoned man. The fullness of her life story—the multivalence of her character and experiences—are reduced to an offence linked to her son. In contemporary colloquial speech, Shelomith might be talked about as ‘that woman’ whose son did ‘that thing’ (Gafney 2017: 127). As with Rooney’s Eve Alone, it requires the imagination of artists, scholars, and readers to create spaces for Shelomith to be explored as a complex woman whose life may have been more than the selective circumstances narrated in the Scriptures.

References

Rooney, Julia. 2018. ‘Eve Alone and Portalscreen: Artist’s Statement’, available at https://divinity.yale.edu/news/eve-alone-and-portalscreen [Accessed 18 August 2022]

Gafney, Wilda C. 2017. Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press)

Unknown artist

Emmett Till and his mother, Mamie Till Bradley, c.1950, Photograph, NAACP Records, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; 24.00.00, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Visual Materials from the Rosa Parks Papers, https://www.loc.gov/item/2015650432/

Without / Because

Commentary by Xiao Situ

This photograph of Mamie Till-Mobley and her thirteen-year-old son Emmett Till was taken in their Chicago home at Christmas in 1954. Emmett is wearing the new clothes he has just been gifted, and his mother’s coiffed hair and translucent balloon sleeves lends an air of buoyancy to the holiday festivities. A patterned sofa and framed picture hint at the cosiness of their living room, and the strong lateral lighting adds drama to the captured scene.

Till-Mobley understood the power of images. Just nine months after this portrait was taken, she decided to attach it—alongside two other portraits of Emmett—to the inside of his casket in preparation for his funeral on 5 September 1955 at the Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ in Chicago. Earlier that August, while visiting relatives in rural Mississippi, Emmett was kidnapped, tortured, disfigured, and brutally murdered by two white men, his body left to rot in the Tallahatchie River.

Till-Mobley chose to hold a public, open-casket funeral. ‘Let the world see what I’ve seen’, she said (Till-Mobley and Benson 2003: 139). Nearly 100,000 people paid their respects to Emmett’s misshapen form. They also saw the three handsome portraits that Till-Mobley had tacked upon the lid. Through visual juxtaposition, her ‘exhibition’ made clear how racism could twist humanity into something grotesque and utterly unrecognizable.

Emmett lived for just fourteen years, yet his life and death completely reoriented his mother’s universe. Henceforth, Till-Mobley dedicated her life to social justice until her death at age 82 in 2003, recognized as a key activist in the civil rights movement. She wrote, ‘Although I have lived so much of my entire life without Emmett, I have lived my entire life because of him’ (Till-Mobley and Benson 2003: 282).

Like Till-Mobley, Shelomith bat Dibri probably didn’t seek to be of any historical significance. Certainly, she didn’t plan her legacy in Israel’s annals to be founded upon notoriety. Both mothers likely felt that the publicity they received in connection with their sons came at too high a price. While Till-Mobley was able to transform her personal pain into a higher communal purpose, Leviticus gives us no clues about how Shelomith fared. By meditating on Shelomith’s experience in light of Till-Mobley’s story, however, we can perhaps restore to Shelomith the maternal solidarity and empathy she needed.

References

Till-Mobley, Mamie, and Christopher Benson. 2003. Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime that Changed America (New York: Random House)

Barbara Hepworth :

Mother and Child, 1934 , Cumberland alabaster on marble base

Julia Rooney :

Eve Alone, 2017 , Oil pant and photo collage on plaster, with chiffon overlay

Unknown artist :

Emmett Till and his mother, Mamie Till Bradley, c.1950 , Photograph

Mothers and Sons

Comparative commentary by Xiao Situ

Although it was the son who cursed God’s name and engaged in a fight with another man in the camp, the son remains unnamed in Leviticus 24. Instead, the son’s misconduct is tied to his mother’s name: Shelomith bat Dibri, the only named woman in Leviticus. This suggests that Shelomith, at least according to the author of Leviticus, is somehow ultimately to blame for her son’s bad behaviour.

Shelomith and her son are rendered as one-dimensional figures in Leviticus. They serve as negative examples in a book about purity and violations, about rituals and regulations. Shelomith especially seems to bear the brunt of malignment in the narrative, since it is her name—not her son’s—that is invoked in connection to his misdeeds. As with many parts of Scripture, Leviticus leaves the work of subtlety and complexity up to its readers.

These are some of the questions that arise when Leviticus 24 is considered from a feminist perspective. Was Shelomith’s sexual relationship with an Egyptian man—and the son that was conceived from that union—a point of controversy among the Israelites? What was Shelomith’s relationship like with her son? Why did the son end up living with his mother among the Israelites rather than his father? Was the father still in the picture? Was the son’s interethnic identity a cause of social tension within the camp, perhaps even instigating the fight that occurred between him and the other man? Did the son curse God because of the social rejection he experienced living among the Israelites? Was the son perhaps wrongfully and prejudicially punished? Is Leviticus 24 not just about the violation of blasphemy and its punishment, but also about the negative social implications of an Israelite woman’s sexual relations with an outsider?

We may never get definitive answers to these questions, but it is the empathetic speculation that matters, that can do transformative work for the legacy of Shelomith bat Dibri. The three artworks featured in this exhibition are feminist interventions in one-dimensional accounts of women in the Bible. Julia Rooney’s Eve Alone provides pictorial space for Eve (and by extension, Shelomith) to be more or other than her conventional portrayals in Scripture and visual culture.

The formal intricacies in Barbara Hepworth’s Mother and Child help us to consider the complexities of the interethnic parent–child relationship between Shelomith and her son. The physical possibility of the smaller pebble’s removal from the larger stone mass invites us to imagine how Shelomith’s life might have been different had her son been out of the picture. Would it have been one of greater ease if less history-making drama? Would she not have been mentioned in Leviticus at all?

And finally, by reading Shelomith’s sparse story alongside the fuller, richer account of Mamie Till-Mobley’s, we can recuperate some of the feelings, thoughts, and struggles Shelomith may have experienced in losing her son, especially in the context of scandal and violence. The stories of Shelomith and Till-Mobley differ in significant ways. Most notably, while there is no question that Till-Mobley’s son was murdered because of his race, Leviticus cites blasphemy as the reason for the execution of Shelomith’s son. Yet situating the two women side-by-side generates an interpretive possibility that narrows even this point of difference. A womanist perspective might consider the prospect that Shelomith’s son, too, may have been executed due to his racial difference, with the charge of blasphemy as a veiled justification. The presence of this half-Egyptian man birthed by an Israelite woman could have been met with so much intolerance within the camp that the son was intentionally provoked into a fight that would land him in trouble. By bringing the stories of these two mothers into proximity, this racial component of Shelomith’s narrative becomes clearer.

In addition to the three artworks featured in this exhibition, the Bible itself provides its own intervention in relation to the scant treatment Shelomith receives in Leviticus. We can find it in the New Testament account of Mary and Jesus: here again is a woman whose pregnancy was likely a cause of scandal, whose son engaged in questionable activities, and who ultimately had to witness her son’s punishment and execution. Considered alongside this higher-profile story, the narrative of Shelomith and her son can be seen not simply as one about dishonourable behaviour and its subsequent punishment, but as a foreshadowing of the archetypal mother–son relationship within Christianity.

References

Gafney, Wilda C. 2017. Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press)

Commentaries by Xiao Situ