Psalm 42–43

Thirsting for God

Katsushika Hokusai

Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura; The Great Wave), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei), c.1830–32, Polychrome woodblock print; ink and colour on paper, 257 x 379 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929, JP1847, www.metmuseum.org

Under the Wave: A Boundary-Crossing Icon

Commentary by Ellen F. Davis

Almost certainly the Buddhist Katsushika Hokusai knew nothing of the Psalms. When he created this woodblock print, Christianity had been banned in Japan for two centuries. The ban remained in force (1615–1868) until after his death. Earlier poets and painters had made waves central to the national imagination—viewed as both a protection against intruders and a danger, discouraging foreign travel. Yet within a few decades, this image from the ‘closed country’ would begin to instruct the Western imagination about Japan. Over the last century at least, Hokusai’s Under the Wave has attained the status of a global icon, a boundary-crossing image capable of communicating with viewers in multiple religious traditions and cultures.

In Israelite and Japanese religious cultures, mountains and the sea are viewed as awesome in the true sense—life-giving and fearsome—and thus evocative of divinity. Although they come from the eastern and western extremes of the Asian continent, respectively, Hokusai’s image and Psalms 42–43 (originally a single psalm) share two elements of their landscapes: mountains and deep waters.

Japanese and Western viewers are likely to read the print differently from one another. For Westerners, reading left to right, the towering wave is first and foremost. Asian viewers, trained to read from the opposite direction, might focus instead on what stands ‘under the wave’ (Hokusai’s own title): Mount Fuji, the sacred volcano, both dangerous and revered.

Refocusing on Fuji as a sign of divinity may yield a better understanding of the watery paradox central to Psalm 42: the psalmist yearns for God’s presence in the midst of troubles that also seem to come from God. God’s ‘waves and billows’ threaten to overwhelm, but still ‘deep calls to deep’ (42:7 own translation), the depths of affliction to the depths of faith. God is present here. A Christian viewer might press further. The three-lobed cloud hovering over Fuji’s peak—could that be a cruciform figure with arms outstretched, a sign of divine presence to those in distress?

References

Guth, Christine. 2015. Hokusai’s Great Wave: Biography of a Global Icon (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press)

Terry, Charles S. 1959. Hokusai’s 36 Views of Mt. Fuji (Tokyo: Toto Shuppan)

Terror, Transience, Transcendence

Commentary by Ellen F. Davis

Fuji and waves are both themes central to Katsushika Hokusai’s imagination; he depicts each of them dozens of times, in states ranging from serenity to rage. Here the mammoth wave soars to its peak, an instant before it will crash down over three fishing skiffs and the men huddled within. Shown in deep perspective—an innovation borrowed from Western artists—the foaming edge simultaneously descends, like snow on the mountain peak which seems to rise out of one of the boats.

In Buddhist tradition, the enduring nature of Fuji highlights—by way of contrast—the transience of human existence; fu-ji is literally ‘no death.’ Visible from Hokusai’s home city of Edo (Tokyo), he dwells on the sacred mountain as an image of changelessness and immortality, by comparison with the ‘floating world’ of everyday reality. Yet Hokusai distinguishes himself from traditional artists by also exploring in depth daily life in Japan’s chic new capital city. Earlier artists focused on ceremony, high society, ‘pure’ nature, but this master draftsman, painter, and printmaker looks carefully at everyone: peasants and geishas, butchers and laundrywomen, victims of rape and the most recent eruption of Fuji—or (as here) fishermen pursuing their dangerous occupation.

Notably, Hokusai’s visions of Fuji were mass-produced prints—in this series alone, thirty-six images, a number signifying completeness. A single sheet sold for little more than the price of a bowl of noodles. Thus they circulated widely among tourists, townspeople of all classes, and pilgrims who came by the thousands each year to climb the sacred mountain, hoping to glimpse a reality that transcends the floating world of pleasure-seeking and pain.

Likewise, Psalms 42–43 (originally a single psalm) express a pilgrim’s longing for God’s ‘holy mountain’ (43:3), presumably Jerusalem. Wandering in distant places, literally or metaphorically, the psalmist prays that divine light and truth will lead her to the place where God’s saving presence is a palpable reality.

References

Baatsch, Henri-Alexis. 2016. Hokusai: A Life in Drawing (London: Thames & Hudson)

Lane, Richard. 1989. Hokusai: Life and Work (London: Barrie & Jenkins)

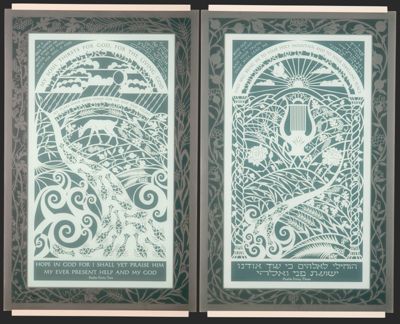

Diane Palley

Psalm 42–43, 2005, Silkscreened and sandblasted glass panels, 121.92 x 213.36 cm, Duke University Divinity School, Durham, North Carolina; © Diane Palley

From Tears to Praise

Commentary by Ellen F. Davis

‘My tears have been food for me day and night’ (Psalm 42:3)—the psalmist’s surprising image of being fed by tears inspires this visual midrash (imaginative scriptural commentary in Jewish tradition). The twin architectural panels on the once conjoined Psalms 42–43 follow designs Diane Palley originally developed in the Jewish folk-art medium of papercut.

In the first panel, fructifying rain shaped like tears falls to earth. In response, the terraced hills yield the legendary seven fruits of the land of Israel: figs, grapes, dates, pomegranates, olives, wheat, and barley. Adapting that biblical and Jewish tradition for a Christian worship space, Palley frames this panel with the growth cycles of wheat and grapes, the elements of the Eucharist.

The figure of the deer is highlighted by converging lines, where the ridge of hills meets the billowing waters. Head down, it approaches a stream filled with eighteen fish, representing the most important prayer of the synagogue, the Shmoneh Esrei (‘eighteen’), which praises God in a lengthy series of blessings. In this context the fish symbol is deliberately ambiguous; for Christian worshippers it may recall the acrostic of one of the earliest Greek affirmations of faith: ICHTHYS: Iēsous Christos, Theou Yios, Sōtēr (Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour).

Following the fish down the turbulent stream, the eye moves to the strong affirmation of hope in God that is the psalm’s refrain (Psalm 42:5, 11; 43:5). In the second panel, three fish—a reference to the Trinity—swim in a now-calm stream through the fertile land. The visual movement is upward, to David’s harp (symbolizing praise), which is framed by wheat and grapes, blooming roses (a transcultural symbol of divine love), a crown, and the rising sun: ‘They will bring me to your holy mountain…’ (43:3). Praise persisting through tribulation leads to life in abundance. Hence the composition is framed by the growth cycle of the many-seeded pomegranate, a biblical symbol for God’s gift of life (and, for Christians, of resurrection).

Healing Desire

Commentary by Ellen F. Davis

Oh send out thy light and thy truth; let them lead me, let them bring me to thy holy hill, and to thy dwelling! (Psalm 43:3)

The great Hasidic rabbi and mystic, Reb Nachman of Bratslav (1772–1810), famously taught that Psalm 42 is one of ten psalms that promote spiritual healing. Diane Palley’s panels imply Reb Nachman’s insight that right desire is itself the greatest source of healing from the chronic depression and dissatisfaction that stem from alienation from God.

The psalmist’s repeated counsel to her own soul—‘Hope in God…’—appears, in English and Hebrew, at the base of each panel. That positioning suggests that the determination to keep hoping in God is foundational for the spiritual life. Even in the midst of the greatest distress, healing begins with the conviction that I will again have reason to offer genuine praise to God.

Hope is concentrated in the figure of the thirsty, persistent deer, the creature that through the centuries has often appeared in Jewish poetry, both secular and religious, as a figure for Israel in its beauty and vulnerability. From our viewer’s perspective, we can be assured that the deer’s desire will soon be satisfied. The brook is close at hand, and both the abundance of fish and the rich plant-life on the banks attest to the health of its waters.

Water, food, light—these images in both the psalm and Palley’s rendering of it evoke the prayer of another psalmist-pilgrim to God’s holy mountain: ‘With you is the fountain of life; in your light, we see light’ (Psalm 36:9 own translation).

References

Band, Debra. 2007. I Will Wake the Dawn: Illuminated Psalms (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society)

Unknown artist

The Tree of Life (Apse Mosaic of San Clemente), c.1130, Mosaic, Basilica of San Clemente al Laterano, Rome; Scala / Art Resource, NY

A Picture of Salvation

Commentary by Ellen F. Davis

The thirsty deer of Psalm 42 stands at the foot of the cross in the Apse Mosaic, the crown jewel of the twelfth-century church of San Clemente in Rome. In fact, three deer constitute the foundation of the glowing composition, which offers a condensed visual account of all salvation history and the work of the three Persons of the Trinity.

At the bottom, two deer slake their thirst from the four rivers that flow from Eden (Genesis 2:10). Just above, one deer, encircled by a red serpent, drinks from a great body of water. Is this the primeval deep (Genesis 1)? Or the river of the water of life (Revelation 22:1)? The image may recall an ancient belief that deer eat venomous snakes, neutralizing their poison with copious quantities of water. Psalm 42 figured prominently in baptismal liturgies, and medieval viewers would have recognized in the scene allusions to the soul’s thirst for God’s grace and deliverance from deadly sin through the sacrament.

Above the lone deer spreads an acanthus plant. Greeks associated its thorny, aromatic leaves with victory over suffering, and Christians with resurrection; in John’s Gospel (19:2), the soldiers plait a crown of akanthos for Jesus. Here the cross rises from the plant and stretches nearly the height of the apse, to where a divine hand reaches down to crown him with a victory wreath. The cross is surrounded by thorns and studded with twelve doves, symbolizing the apostles in their innocence (Matthew 10:16).

The gold background that fills the apse represents the divine glory that fills the world through the discrete actions of the Triune God: the original creation (Eden), Jesus’s victory on the cross, and the renewal of creation through the Spirit of the crucified and risen Christ.

References

Oakeshott, Walter. 1967. The Mosaics of Rome: From the Third to the Fourteenth Centuries (London: Thames & Hudson)

The Second Tree of Life

Commentary by Ellen F. Davis

‘Send out your light and your truth; they will lead me’, the psalmist prays (Psalm 43:3 own translation). In stone, glass, and gold, this mosaic seems also to achieve a ‘sending out’, disclosing the distinctive beauty of each of God’s creatures.

Ancient Christian legend maintained that the cross erected on Golgotha stood in the very same spot on earth where God had once planted the tree of life. The Apse Mosaic develops the full theological potential of that legend.

On either side of the cross the acanthus plant, watered by the streams of Paradise, extends its tendrils. ‘We liken the church of Christ to this vine’, begins the Latin inscription at the bottom of the apse. Fifty spiralling vines fill the entire space, even dwarfing the cross. The number fifty recalls the church receiving the Spirit on Pentecost, fifty days after Passover and the Resurrection, and further the Jubilee, the fiftieth year, a year of liberation for the oppressed that Jesus proclaimed (Luke 4:18–19). Each of the tendrils bursts into flower or fruit at its tip; this is the ever-bearing tree of Paradise (Revelation 22:2). Growing around the cross, it reveals Golgotha as the site where God’s creative and redemptive work culminates.

In a visual summary of the created order, the full spectrum of the medieval Christian world is shown nestled among the vines, with all of its members pursuing characteristic activities. Here are countless birds and winged cherubs, princes and nobles, eminent theologians with book and pen in hand, tonsured monks in the kitchen, a woman feeding chickens, women and men tending sheep and goats, a family in conversation, youths gesturing into space. The effect of variety is enhanced by the mosaicists’ technique—a medieval innovation—of working on a rough mortar surface, so the slightly uneven plane of tesserae catches light at different angles.

‘Send out your light and your truth…’ Perhaps the artists who produced this work of almost unrivalled luminosity found in that prayer a reflection of their own vocation.

References

Poeschke, Joachim. 2010. Italian Mosaics, 300–1300, trans. by Russell Stockman (New York: Abbeville Press Publishers)

Sundell, Michael G. 2007. Mosaics in the Eternal City (Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies)

Katsushika Hokusai :

Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura; The Great Wave), from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei), c.1830–32 , Polychrome woodblock print; ink and colour on paper

Diane Palley :

Psalm 42–43, 2005 , Silkscreened and sandblasted glass panels

Unknown artist :

The Tree of Life (Apse Mosaic of San Clemente), c.1130 , Mosaic

Refusing to Despair

Comparative commentary by Ellen F. Davis

All the works here were created for a wide public, not just for wealthy or sophisticated patrons of the arts. The medieval Apse Mosaic and Diane Palley’s 2005 architectural panels are permanently and prominently installed, respectively in a church and a university chapel. Long before Katsushika Hokusai’s nineteenth-century prints hung in prestigious museums, thousands of ordinary people purchased them as mementos, decorations, aids to pilgrimage. Meticulously crafted though they are, each of these works is fundamentally popular art, like the bipartite Psalm 42–43 itself. The artists have used consummate skill and the resources of three different religious traditions—Buddhism, Christianity, and (in Palley’s case) Judaism—to explore a condition basic to human experience altogether: our susceptibility to affliction both physical and spiritual. We cannot forget that we will suffer and die. However, their images point also to the source of hope, the divine reality that transcends the present moment of affliction.

The condition of human vulnerability is most explicit in Hokusai’s woodblock image print: the fishermen are in immediate danger of drowning. We will never know if they made it alive through the wave—yet in the distance stands Fuji, a reminder of another, more enduring order of existence. Hokusai was a master of realism; for that very reason he was in his own day celebrated by the masses but regarded as vulgar by the cultural elite. The ‘vulgar’ quality of Under the Wave off Kanagawa also contributes to its modern status as a global icon. It seems to speak a universal language, even if the message it conveys may differ across contexts, cultures, and centuries. That status seems unattainable for the other pieces, which each draw on multiple symbols particular to the iconography of Judaism and Christianity. Yet even so, the specificity of tradition is more inspiring than confining. Most notably, Diane Palley has deliberately created a measure of hybridity by adapting Jewish traditions to a Christian context.

These images are frank in displaying longing, danger, even the imminent threat of death, but none of them is merely desperate. Diverse though the several compositions are, they all share one stylistic feature: through careful ordering of the pictorial plane, they tacitly assert that the world we inhabit may be harsh, but it is not chaotic. Hokusai suggests as much by his innovative perspective; one of the threatened boats seems to touch Fuji (‘no-death’), even as it heads straight into the wave. Again, the Apse Mosaicist shows an emaciated, nearly naked body bleeding on a cross, yet the instrument of death stands at the very centre of the tree of life, which fills the luminous space. Similarly, Palley’s panels (one shown here) are created from images of architectural elegance that depict abundant life, even as she cites the psalmist’s words of intense longing and hope.

The beautifully ordered Hebrew poem that inspires this exhibition likewise represents the refusal to despair. This most introspective of the biblical laments shows the psalmist challenging her own despondency: ‘Why are you cast down, O my soul?’ (42:5, 11; 43:5). Lament is an inherently dynamic form of prayer; here the speaker moves, albeit fitfully, from the fear of abandonment by God to the determination to offer praise. That movement toward praise is rarely completed in any psalm. Part of the profound realism of the laments is that they generally end with praise still in the future tense: ‘I shall again praise [God]’ (Psalm 43:5) …someday.

Our psalmist is a spiritual pilgrim, on the way from affliction to praise, and so it is fitting that none of the images exhibited here is either static or idyllic. Each depicts fear, pain, danger, even as they point in their several visual languages and religious traditions to a beautiful world that gives life to all creatures, to life that finally defeats death and despair. These works are complementary expressions of an insight that is central to the biblical laments, including Jesus’s cry of dereliction from the cross: the inability to feel God’s presence in suffering is terrible, but that is not itself the cause of despair. Rather, despair overwhelms the soul that stands still; only when we stop looking for divine presence does the sense of absence become absolute, final.

Knowing God’s presence is not a fixed state of the soul. Rather, it is a movement, a restlessness generated by holy desire. That is a pilgrim’s wisdom, which these artists invite us to contemplate.

Commentaries by Ellen F. Davis