1 Samuel 28:3–25

The Witch of Endor

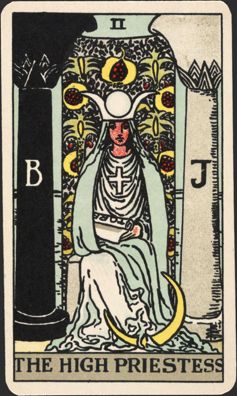

Pamela Colman Smith

High Priestess from the series of 22 Major Arcana, popularly known as the Waite pack, c.1937, Colour lithography, 12 x 7 cm, The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library Collection, Yale University Library; 2003230, Photo: The Beinecke Library / Public Domain

Keeper of Secrets

Commentary by Simone Kotva

This iconic High Priestess card depicting a robed, seated woman with a lunar crescent at her feet and the crown of Isis on her head was drawn by Pamela Colman Smith for the popular tarot deck designed by Arthur Edward Waite and first published in 1910 by Rider & Co.

Waite and Smith were both members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, an initiatory society dedicated to the study and practice of ceremonial magic, and their tarot deck is based on Golden Dawn teachings (Greer 1995: 405–10). Central to the Golden Dawn was the recovery of the divine feminine, whose allegorical form the High Priestess is supposed to embody: seated between Jachin and Boaz, the two pillars of Solomon’s Temple (1 Kings 7:21), she keeps the balance of powers; placed before the veil of pomegranates (a fruit traditionally associated with Persephone’s descent and release from the underworld), she guards the key to the mysteries of life and death (Waite [1911] 2005: 29–70).

A hugely influential piece of art created just as the women’s suffrage movement was rising to prominence, Waite–Smith’s deck and the High Priestess card in particular speak to the changing perception of women in the twentieth century (Auger 2004: 13–52). We need only compare Smith’s arresting priestess to early modern depictions of witches—with their delight in the grotesque and the degrading—to recognize an entirely new portrayal of what women’s powers might look like. And yet not entirely new. When read against 1 Samuel 28, the poise of the High Priestess in the Waite–Smith deck reminds one of the least cited but surely most remarkable among the woman of Endor’s attributes: her equanimity.

When, after the spirit of Samuel appears to Saul, the king falls to the ground in a swooning fit, the woman is the first to act, making sure he has regained his strength before returning home. The king’s illness would have given the woman the perfect opportunity to flee the scene: after all, she has been tricked into performing magic that might get her banished from the land. Instead, this ‘witch’ responds with civility and good grace, and not a trace of cackling laughter. It is not difficult to judge which image of woman’s magic she most resembles—the hag or the High Priestess.

References

Auger, Emily E. 2004. Tarot and Other Meditation Decks: History, Theory, Aesthetics, Typology (Jefferson: McFarland)

Greer, Mary. 1995. ‘Pamela Colman Smith and the Tarot’, in Women of the Golden Dawn: Rebels and Priestesses (Richmond, Vermont: Park Street Press), pp. 405–10

Waite, Arthur Edward. [1911] 2005. The Pictorial Key to the Tarot: Being Fragments of a Secret Tradition Under the Veil of Divination (Mineola: Dover)

Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen

Saul and the Witch of Endor, 1526, Oil on panel, 85.5 x 122.8 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; SK-A-668, Photo: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Wild and Untamed

Commentary by Simone Kotva

Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen’s Saul and the Witch of Endor (1526) was painted at the very beginning of the witch craze in early modern Europe, and anticipates later, lurid depictions of the woman of Endor as a fearsome hag. The early modern period saw differences between male and female magic. While the learned magic of the magus could be seen as divinely sanctioned, even respectable, woman’s magic was considered ‘wild’ and ‘untamed’, like the natural world with which women’s bodies were so often compared (Merchant 1980: 127–48).

The unruliness of women’s magic, and its relationship to the respectable art of the male magus, is at the heart of Van Oostsanen’s depiction of the woman of Endor. On the one hand, we notice several references to a well-known Renaissance grimoire of learned magic, The Key of Solomon the King. The woman is depicted in the midst of a spirit-conjuration as instructed by the Key: the grimoire requires the magus to draw a protective circle around himself while reciting psalms, lighting incense, and writing the name of God. Hence the two tapers in the woman’s hands, the circle at her feet, and her half-open mouth, poised as if to speak. Deus, ‘God’, is the last word on the page of the book from which the woman is reading (Peacock 2017: 663; Mathers and Peterson: 2016).

Yet those attributes of the learned magus which seem to elevate the woman’s status also debase her by the same stroke. In Van Oostsanen’s painting the woman transgresses gender roles in a manner clearly meant by the painter to be an occasion for ridicule rather than reverence: her bared, sagging breasts, puckered skin, and generally unlovely visage gesture at the perceived unloveliness of her work. A dark cloud and a host of strange-looking creatures descend from top right, alluding to the unruly forces of the natural world and to the direct connection women were thought to have with these powers. And the woman of Endor herself is unruly, trespassing as she does on a man’s circle of power, speaking words reserved for a male magus.

While Van Oostsanen’s woman of Endor is made to perform the respectable magic of Solomon, the fact that she is a woman means that her execution of learned magic can only ever be a performance: at bottom she remains the ‘witch’ and evildoer of the painting’s title.

References

Merchant, Carolyn. 1980. The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution (New York: HarperCollins)

Moffitt Peacock, Martha. 2017. ‘Magic in Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen’s Saul and the Witch of Endor’, in Magic and Magicians in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Time: The Occult in Pre-modern Sciences, Medicine, Literature, Religion, and Astrology, ed. by Albrecht Classen (Berlin: De Gruyter), pp. 657–80

Peterson, Joseph (ed.), and S. L. MacGregor-Mathers (trans.). [1889] 2016. The Key of Solomon the King: Clavicula Salomonis. A Magical Grimoire of Sigils and Rituals for Summoning and Mastering Spirits (Newburyport, MA: Weiser)

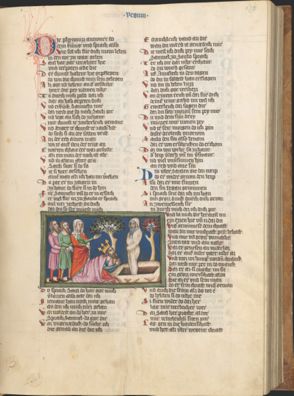

Unknown artist

Saul and the Witch of Endor, from German World Chronicle, c.1360, Illumination on vellum, 343 x 242 mm, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; MS M.769, fol. 172r, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

A Christological Witch

Commentary by Simone Kotva

In this illumination from a fourteenth-century German chronicle, the anonymous artist shows the spirit of Samuel predicting the downfall of Saul, here shown kneeling in front of Samuel’s opened tomb. The woman of Endor stands left of centre: dressed in a blue gown and red cloak, wearing a white headdress, she is depicted as a person of noble birth, respectable and refined. Confidently she gestures at the spirit of Samuel, while at her feet Saul the king bows in fear.

It is an image quite unlike the sensationalist portrayals of the woman of Endor in many Early Modern illustrations and paintings, which picture the woman as a malefic hag. But the German chronicle was composed well before the witch craze of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and in medieval illuminations like this one it is unusual to see the woman of Endor painted with negative attributes (Peacock 2017: 260–61).

This is despite the fact that the Hebrew Bible contains several prohibitions against magic. 1 Samuel 28 itself is no exception: we are told that, prior to his desire to speak with the spirit of Samuel, Saul had banished all the ‘wizards and mediums’ (v.3). Why then is there no hint of evildoing in this medieval depiction of Saul and the woman of Endor?

The answer may be found by revisiting some of the earliest Christian commentary on this passage (Copeland 2014: 308). While early modern visual interpretations connect the evildoing at Endor to the woman and her profession, many older biblical commentators tended to link the evildoing instead to Saul, the subject, in this story, of God’s anger and of Samuel’s indignation. Origen of Alexandria, for instance, was able to interpret the woman of Endor as a conduit for God’s anger at Saul rather than as an agent of evil, and to compare her to Christ rather than to a sorceress (Murphy 2010: 266; Smelik 1977).

It is this Christ-typology that explains her striking appearance in the German chronicle. Here she is dressed in red, a colour often associated with Christ, and moreover raises a body from an opened grave. Far from being a nefarious act of spirit-conjuration, this (as Origen had suggested) bears a striking resemblance to the story of the raising of Lazarus from his tomb (John 11:1–44; Peacock 2017: 661).

References

Aran Murphy, Francesca. 2010. 1 Samuel, Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible (Grand Rapids: Brazos)

Copeland, Kirsti Barrett. 2014. ‘Sorceresses and Sorcerers in Early Christian Tours of Hell’, in Daughters of Hecate: Women and Magic in the Ancient World, ed. by Kimberly B. Stratton and Dayna S. Kalleres (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp. 298–318

Peacock, Martha Moffitt. 2017. ‘Magic in Jacob Cornelisz van Oostanen’s Saul and the Witch of Endor’, in Magic and Magicians in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Time: The Occult in Pre-modern Sciences, Medicine, Literature, Religion, and Astrology, ed. by Albrecht Classen (Berlin: De Gruyter), pp. 657–80

Smelik, K.A. D. 1977. ‘The Witch of Endor: 1 Samuel 28 in Rabbinic and Christian Exegesis until AD 800’, Vigilae christianae 33: 160–79

Pamela Colman Smith :

High Priestess from the series of 22 Major Arcana, popularly known as the Waite pack, c.1937 , Colour lithography

Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen :

Saul and the Witch of Endor, 1526 , Oil on panel

Unknown artist :

Saul and the Witch of Endor, from German World Chronicle, c.1360 , Illumination on vellum

Demonic and Divine

Comparative commentary by Simone Kotva

Why these wildly divergent, even contradictory, portrayals of the woman of Endor? How can she be depicted both as a type of Christ—as in the fourteenth-century illumination from the German chronicle—and as the loathsome hag in Jacob van Oostsanen’s Saul and the Witch of Endor?

One would have thought it easy and straightforward to paint her as an evildoer, in the manner of Van Oostsanen, given that the biblical text contains so many prohibitions against magic (1 Samuel 28:3; Exodus 22:18; see Hutton 2017: 51–54). But perhaps the matter is less simple. For is not magic an ability to communicate with forces more awesome and powerful than oneself? And did not Christ do something similar when he prayed to God that Lazarus might be raised from the dead? (Smith 1978: 81–139). Christ is clear that he performs his miracles not by himself, but by the power of the Holy Spirit that acts through him from the Father (John 5:30; Acts 10:38). Well then, who is to say that the woman of Endor did not act by the power of the same spirit?

But in the ancient world spirits were many and it was not easy to know or verify that the spirit invoked by one person was the same as that prayed to by another. There were many daimones, many invisible intelligences carrying messages from gods to humans and petitions from humans to gods (Skinner 2014). To the ancient mind, the question was not whether or not the woman of Endor really did raise the spirit of Samuel, but by which spirit she raised it and whether or not Samuel’s ghost was a malefic illusion sent by an evil spirit or whether its arrival was caused by the will of God (Copeland 2014: 314). To the anonymous illuminator of the German chronicle it seemed (as it had done also to Origen) that there was something ineluctably divine about the magic of Endor.

Even in the ancient world, however, the attitude toward magic and spirits was not without the opprobrium levelled at it in later centuries. While Augustine, for instance, found it difficult to deny that the ghost of Samuel had spoken God’s truth and predicted, accurately, Saul’s downfall, he was not as ready as Origen had been to compare the woman of Endor herself to Christ. For Augustine, the woman was still to be condemned for practising sorcery and associating with evil spirits through her art (On Christian Doctrine 2.35).

Augustine’s condemnation of the woman and her magic anticipates what, in the painting of Van Oostsanen, has become a delight in the grotesque and degrading. From the onset of the witch craze in the sixteenth century, visual representations of the magic at Endor such as Van Oostsanen’s were influenced strongly by sensationalist portrayals of naked women gathering to perform magic for nefarious purposes. Van Oostsanen’s woman of Endor calls to mind Albrecht Dürer’s famous engraving of The Witch (c.1500)—and the female figures descending onto the scene at upper right are riding, like Dürer’s witch, on goats (Zika 2017).

From the early modern period onward, the possibility of representing the woman of Endor, which is to say woman’s magic, would reside in the image of the witch and of witchcraft as such. That image would not alter substantially until the emergence of the occult revival and of the modern women’s movement in the late nineteenth century. It was then that the sensationalism associated with women’s magic first began to be questioned seriously and the witch reimagined as a person of power and mystery, rather than of maleficence, more akin to a sibyl or a pagan priestess than to Dürer’s caricature of an early modern witch.

Pamela Colman Smith’s High Priestess card from the 1910 Waite–Smith Tarot deck, with its allusions to Solomon’s Temple and the mysteries of Persephone, is an example of the most popular and influential reimagining of woman’s magic along these lines. It had been prepared for, earlier in the nineteenth century, by a number of depictions—among them two striking images by Russian painters Dmitry Martynov and Nikolai Ge—which portrayed the woman of Endor as a tall figure with stately and formidable bearing. Though these images do not engage explicitly with the Christ-typology, their depictions of the woman of Endor seem to recover important aspects of a tradition of interpretation that pre-dates the witch-trials but which look forward, also, to the Neopagans and female magi of the twentieth century who have chosen to reclaim the name of ‘witch’ for their own (Starhawk 1982: 1–14).

References

Copeland, Kirsti Barrett. 2014. ‘Sorceresses and Sorcerers in Early Christian Tours of Hell’, in Daughters of Hecate: Women and Magic in the Ancient World, ed. by Kimberly B. Stratton and Dayna S. Kalleres (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp. 298–318

Hutton, Ronald. 2017. The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Peacock, Martha Moffitt. 2017. ‘Magic in Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen’s Saul and the Witch of Endor’, in Magic and Magicians in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Time: The Occult in Pre-modern Sciences, Medicine, Literature, Religion, and Astrology, ed. by Albrecht Classen (Berlin: De Gruyter), pp. 657–80

Skinner, Stephen. 2014.Techniques of Graeco-Egyptian Magic (Singapore: Golden Hoard)

Smith, Morton. 1978. Jesus the Magician (San Francisco: Harper Collins)

Starhawk (Miriam Simos). 1982. Dreaming the Dark: Magic, Sex, and Politics (Boston: Beacon Press)

Zika, Charles. 2017. ‘The Witch and Magician in European Art’, in The Oxford Illustrated History of Witchcraft & Magic, ed. by Owen Davies (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp. 134–67

Commentaries by Simone Kotva