Exodus 30

The Altar of Incense

Unknown Sabaen artist

Incense-burner, 2nd century BCE–1st century BCE, Limestone, 9.5 x 10 cm, The British Museum, London; 1915,0710.6, Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Incense and Presence

Commentary by Anna Gannon

This small painted limestone incense burner, measuring roughly 10 cm on each side, comes from Yemen, historically a major centre of incense production and trade. It is of a traditional type widely used from the late fifth century BCE to the first century BCE.

On its top, darkened by use, is a shallow recess for burning, and listed on its sides are Sabaic words for four aromatic substances: rnd dhb ncm qst. These terms describe specific resins, barks, roots, and plants according to their colour and ‘sweetness’. Similar burners name different substances: so far thirteen nouns have been recorded (Robin 1994: 25–30), and whilst their identification is problematic, their variety offers a glimpse into the importance of perfumes in the ancient world. Although we commonly use the word incense (‘that which is burnt’), the term is generic, and was applied to a number of aromatics, often blended together.

In Exodus 30, God gives strict directives for the composition of the sacred anointing-oil and the most holy and exclusive incense to be burnt ‘in the tent of meeting, where I shall meet you’ (v.36 NRSV). The blend specifies stacte, onycha, galbanum, and pure frankincense, ground to a powder and mixed with salt. Stacte, galbanum and frankincense are botanical resins, whilst the mysterious onycha, much debated, has recently been shown to be derived from the opercula of the shell murex, a by-product of the dye industry for purple and tekhelet (biblical blue). Yarns dyed purple and blue are prescribed in Exodus for the textiles of the Tabernacle (26:36; 27:16) and the high priest’s garments (28:5). Chemical analysis of burnt opercula shows substances essential for fixing the smell of incense and effective for purification purposes.

Thus, God delights in incense that is (in the words of the eucharistic offertory prayer) both ‘fruit of the earth’, and the ‘work of human hands’. In burning it, we offer Him thanks and praise.

But in offering this praise we must also be mindful of the ecological and social stewardship God has entrusted to us. If the ancient trade in aromatics came with an environmental and a human cost, nowadays the very survival of Boswelia sacra (the tree that yields frankincense) is under threat as its habitat suffers the impacts of frequent conflict and environmental damage.

References

Benkendorff, Kirsten. 2017. ‘Modern Science Tackles a Biblical Secret—The Mystery Ingredient in Holy Incense, 12 December 2017’, www.theconversation.com, [accessed 21 August 2019]

Robin, Christian. 1994. ‘Les plantes aromatiques que brûlaient les Sabéens’, in Parfums d’Arabie, Saba. Arts—Littérature—Histoire—Arabie méridionale 1 (Aix-en-Provence), pp. 25–30

Unknown Anglo-Saxon artist

English silver penny, Obverse: knot bust, with hand holding sprig, 720–40, Silver, 12.13 x 12.38 mm; Weight: 1.05g, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; CM.1807-2007, © Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge / Art Resource, NY

Smelling Salvation

Commentary by Anna Gannon

Amongst the most beautiful of Anglo-Saxon coins, this early-eighth-century silver penny from Kent features a bust in profile, with elaborate drapery enriched by jewel-like pellets around its neck and shoulders. At the back of the figure’s head, on the left of the composition, we see flamboyantly looped and knotted wreath-ties. Although at first sight they may resemble a pretzel, the ties cross over to make an emphatic X: the first letter of ‘Christ’ in Greek. We may choose to identify in the bust an image of Christ himself, or the initial X as a powerful invocation of His title: either way, we are made aware that there is a message to be learnt—this is a sermon in miniature.

The figure holds up in his hand a plant identifiable on the right of the composition, bringing it to his nose to inhale its fragrance. This is one of a set of coins which explore the Five Senses, juxtaposing our concrete earthly experience—in this case, the plant’s fragrance—with what transcends our sensory perception and leads to closer relationship with God. The gesture of the figure raising the plant embodies the words of Psalm 141:2: ‘Let my prayer be counted as incense before you, and the lifting up of my hands as an evening sacrifice’ (NRSV).

In addition to rejoicing in God’s creation by celebrating the delight of heady scents, and the healing virtues of some plants, we are here encouraged to meditate on incense as the smell which is truly pleasing to God, and on how God chose to indicate His presence through its fragrance. God meets us through the most ‘basic’ of our senses, the one which (science teaches) travels directly to our most primitive brain centres, in charge of emotions and memories. Fittingly, incense was one of the gifts offered by the Magi, thus underscoring what Bede describes as ‘the humbleness of Christ’s Incarnation’ (Homily 1.19 After Epiphany).

The coin also recalls the collection of Atonement Money (Exodus 30:11–16)—the half shekel for the Sanctuary paid by each adult Israelite to remind them of how God had saved them from bondage in Egypt and brought them back to the Promised Land. In recalling ‘the ransom given for [their] lives’ (v.16), they could reflect on the literal meaning of redemption: their ‘buying back’ by God.

References

Gannon, Anna. 2006. ‘The Five Senses and Anglo-Saxon Coinage’, in Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History, 13, ed. by Sarah Semple (Oxford: Oxbow Books), pp. 97–104

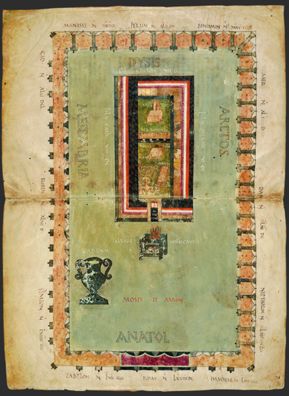

Unknown English artist

The Tabernacle of Moses, from the Codex Amiatinus , Before 716, Illumination on parchment, 500 x 335 mm, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence; MS Amiatino 1, fol. 2v–3r, By permission of the Ministry of Culture

Remaking the Tabernacle

Commentary by Anna Gannon

This double-page ‘map’ of the Tabernacle is found right at the start of the Codex Amiatinus (fols 2v–3), the oldest surviving Latin Bible in one volume. It was written before 716 CE at the Northumbrian twin monasteries of Monkwearmouth–Jarrow. Each of the 1030 leaves measures 50 x 34 cm, and the Codex is 18 cm thick.

The illumination closely follows the blueprint God gave in Exodus: we see a portable tent-like structure, with its framework of acacia wood, housed within a courtyard enclosed by a draped colonnade (Exodus 26; 27:9).

Exodus 30 tells us that within this precinct, and in front of the Tabernacle’s entrance, were to be a large bronze laver for ablutions, and an altar for burnt offerings. Inside the Tabernacle, the sanctuary housed the seven-branched candelabra, the table of showbread, and, before the curtain veiling the Ark of the Covenant, the golden altar of incense.

The recreation of these details in the Codex’s illumination is in many respects very precise—except when it comes to the proportions of the altar of incense. In God’s instruction to Moses, that altar’s height was to be twice the length of its sides (v.2), yet the dimensions in this illumination are akin to those of common near-eastern incense burners—and include a label mentioning an alternative ‘learned’ word for incense, ‘thym(iama)’. Perhaps one of these burners had travelled to Northumbria, together with the incense that we know the monks possessed and used (Farmer 1965: 203). Similarly, the menorah and the curvaceous laver echo actual known models. The monks may have encountered them among the luxury goods imported to adorn their monasteries—Bede tells of ‘countless valuable gifts’ brought back by Benedict for his communities on his fifth journey to Rome (Farmer 1965: 194).

These objects made tangible connections with far-away lands and with the history of salvation.

References

Farmer, D. H. (ed.). 1965. The Age of Bede (London: Penguin)

‘That I may dwell among them’

Commentary by Anna Gannon

The Tabernacle of Moses signified God’s presence amongst His chosen people, sensed through the smell of burning incense. The striking visual images and guiding inscriptions in the early-eighth-century Codex Amiatinus, made in Northumbria, would have enabled the Anglo-Saxon monks then (as they allow us now) to make a virtual pilgrimage to experience worship at that biblical place of God’s presence.

But in making their imaginative journey to Moses’s Tabernacle, the monks could at the same time recognize that the Tabernacle had come to them. Now God’s Word was to be found dwelling within their magnificent Codex, crafted as laboriously and carefully as the Israelites did the Tent of Meeting.

It too would soon be ‘wandering’: it was destined for Rome, as a pledge of the unity of the universal catholic and apostolic Church (O’Reilly 2009). But while it was in their midst, we may imagine them giving thanks for the providential unfolding of salvation that had allowed Christianity to spread to their shores—in the words of the Codex’s dedication, to ‘the furthest boundaries of the Angli’.

References

O’Reilly, Jennifer. 2009. ‘‘All that Peter Stands For’: The Romanitas of the Codex Amiatinus Reconsidered’, in Anglo-Saxon/Irish Relations Before the Vikings, ed. by James Graham-Campbell and Michael Ryan (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Unknown Sabaen artist :

Incense-burner, 2nd century BCE–1st century BCE , Limestone

Unknown Anglo-Saxon artist :

English silver penny, Obverse: knot bust, with hand holding sprig, 720–40 , Silver

Unknown English artist :

The Tabernacle of Moses, from the Codex Amiatinus , Before 716 , Illumination on parchment

Let my Prayer be Counted as Incense

Comparative commentary by Anna Gannon

In the eighth-century text, the Lives of the Abbots of Wearmouth and Jarrow, the Northumbrian Benedictine monk, the Venerable Bede (672/3–735) tells us how in 716 Abbot Ceolfrid made a fateful journey to Rome to present the Codex Amiatinus ‘to the body of the venerable Peter ... head of the Church’ (f.1v; see O’Reilly 2009, Farmer 1965). Before setting off he kindled incense and prayed at the altar before giving his brethren a kiss of peace, ‘thurible in hand’: a pious ritual before his last farewell, as a supplication of divine comfort to his tearful community, and as a linkage to shared ancient worship customs.

The Codex Amiatinus is one of three complete Latin Bibles made in Northumbria: one for each of the twin monasteries, and one intended as a gift to the Pope in Rome—the only one to have survived intact, though ‘hijacked’ to a monastery in the Apennines, as Ceolfrid died en route. It is extraordinary not only in its dimensions (it weighs 34 kg!), but as one of the major Anglo-Saxon intellectual achievements. Its text preserves the most faithful edition of St Jerome’s new Latin translation of the Bible, and the artistic and calligraphic standards are such that until the end of the nineteenth century the Codex was believed to have been sixth-century Italian work.

Bede himself was most probably one of the contributors to the Codex. Some years later, he wrote a commentary on the Tabernacle based on the book of Exodus (24:12–30:31), discussing it allegorically and didactically. There we find a clue for the labelling ‘ALTAR THYM’ in the illumination: it is the abbreviated Greek term for incense (incensum sive thymiama). Incense, Bede tells us, represents prayer, to be offered morning and evening, whilst the Altar of Incense, placed in front of the curtain in the Sanctuary, is seen to signify Christ himself—‘the Word was made flesh and dwelt amongst us’ (John 1:14)—as mediator between God and humankind. This is a pointer to why in the Codex illumination the golden Altar is positioned centrally within the Tabernacle.

Much of the language of the Bible is concerned with imagery derived from nature, and with the fragrances that permeate the Holy Land. Plants symbolize life, growth, abundance, regeneration, and are the subject of many parables. Aromatics such as hyssop were prescribed for cultic purposes and personal cleanliness, while incense is mentioned 170 times. The humble incense burner from Yemen reminds us of the widespread use of aromatic substances in sacrificial practices, but also of their economic importance, and of the complex networks of commerce and cultural contacts that spices engendered.

Incense seems to have been particularly special to Bede: on his deathbed, he distributed his ‘treasures’ amongst his close friends: incense and peppercorns, aromatic tokens from the Holy Land. To him, their smell would have conjured the sacred landscape of the hallowed places about which he so often wrote—a prefiguration of Paradise.

In Anglo-Saxon medicine and belief, knowledge of the virtues and healing powers of native plants was steeped in ancient tradition; in art, however, vegetation motifs were a later, sophisticated import from the Mediterranean world, allusive to Christian ideas and culture.

The coin examined is a case in point: it is roughly contemporary with the Codex Amiatinus and just as innovative and intellectually ambitious. Its imagery, above and beyond the primary impression of pure sensory delight in the sweet scent of a plant, emphasizes the religious importance of the sense of smell as a gateway to human–divine relationship and invites an expansion of our olfactory imagination. It alerts us to the fact that, as with incense, we are in truth smelling salvation. It is one of a thematically interconnected group of five coins. Each illustrates one of the bodily senses and the way it opens access to the experience of God, and each offers a meditation on the transubstantiation of sensory material into the sacred immaterial.

Through burning, incense changes its materiality, becoming a fragrant smoke travelling heavenward to God. Likewise, it transforms our longing into prayers, bringing them to His presence. Through incense, believers’ olfactory experiences and practices are elevated to a sacred sphere transcending time and space, and spanning the practices of different faiths.

References

Ashbrook Harvey, Susan. 2006. Scenting Salvation. Ancient Christianity and the Olfactory Imagination (Berkeley: University of California Press)

Farmer, D. H. (ed.). 1965. The Age of Bede (London: Penguin)

Holder, Arthur G. (trans.). 1994. Bede: On the Tabernacle, Translated Texts for Historians, 18 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press)

Marsden, Richard. 2011. ‘Amiatinus in Italy: The Afterlife of an Anglo-Saxon Book’, in Anglo-Saxon England and the Continent, ed. by Hans Sauer Joanna Story (Tempe, Arizona: ACMRS), pp. 217–43

O’Reilly, Jennifer. 2009. ‘‘All that Peter Stands For’: The Romanitas of the Codex Amiatinus Reconsidered’, in Anglo-Saxon/Irish Relations Before the Vikings, ed. by James Graham-Campbell and Michael Ryan (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Commentaries by Anna Gannon