Matthew 26:47–56; Mark 14:43–52; Luke 22:47–53; John 18:1–11

The Betrayal of Christ

Anthony van Dyck

The Betrayal of Christ, c.1618–20, Oil on canvas, 265.6 x 221.6 cm, Bristol Museum & Art Gallery; Accepted by Her Majesty's Government 'in lieu in situ' of estate duty tax and allocated to Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, 1984, K5177, Bridgeman Images

‘Judas, must you betray me with a kiss?’

Commentary by Angeliki Lymberopoulou

Anthony van Dyck painted this subject three times (the other two are in Minneapolis and in Madrid). Here, the artist has placed Christ slightly off-centre, to the right, allowing Judas to have centre stage.

Judas approaches his master from the left of the composition and clutches Christ’s right hand with his own. The disciple gingerly leans towards Christ to deliver his kiss, while Christ tilts his head towards him to receive it. Christ and Judas stand still in contrast to the surrounding mob’s agitated commotion.

Despite being placed off-centre, Christ remains the first figure that captures the viewer’s eye: he is the only one visible in full, frontal view—a frontal view, typically reserved for the figure of Christ in the iconography of this scene—and has a red mantle wrapped around His left arm, a direct reference to the colour of blood, which he will shed for the salvation of the world. At the same time, Judas is but a yellow ‘mass’, seen from behind; only his wild hair and bushy beard are discernible.

The mob around them is closing in, waiting impatiently for the signal of the kiss to arrest Christ. Just behind Christ, two raised hands holding a piece of rope are visible with the implied intention of placing it around Christ’s neck. The crowd here is formed of people holding spears and lanterns. Neither soldiers nor the figure of Peter cutting off Malchus’s ear are present in this version—possibly because this is the smallest of the three versions of the subject Van Dyck painted (and thus, there was limited space). However, a closer look reveals a sheathed sword at the lower left corner, which could be a visual reference to either or both.

Van Dyck cleverly ‘spills’ the agitation of the gathering into the background: instead of a landscape the artist explores darkness and light, the black colour behind Christ reflecting the ‘darkness’ of the act unfolding before our eyes.

References

Gowing, Laurence. (ed.). 1995. A Bibliographical Dictionary of Artists (Windmill Books Andromeda International)

Russell, Peter. 2019. Anthony Van Dyck, Masters of Art (Hastings: Delphi Classics), (the Bristol ‘Betrayal’ is reproduced wrongly here, showing Christ to the left)

René Magritte

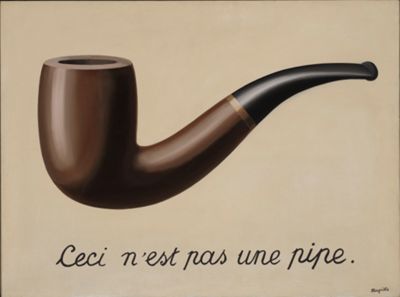

The Treachery of Images (This is Not a Pipe), 1929, Oil on canvas, 60.33 x 81.12 x 2.54 cm, Los Angeles County Museum; Purchased with funds provided by the Mr. and Mrs. William Preston Harrison Collection, 78.7, © C. Herscovici / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo: Digital Image © 2020 Museum Associates / LACMA. Licensed by Art Resource, NY

Fake News?

Commentary by Angeliki Lymberopoulou

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BCE) in his work on the five senses ranks sight as the most important/dominant of all of them; this is also echoed in Souda, the tenth-century lexicon of Byzantine culture.

René Magritte's work challenges our ‘leading’ sense. While right before our eyes we plainly have a curvaceous, two-coloured pipe—its front section brown, its back section black, with a circle in gold separating the two colours—its caption informs us authoritatively that this is not a pipe. What deceives us here: our eyes or the creator of the image (via his painted inscription)? If sight is the ‘top’ sense, how could we possibly disregard what it delivers to us and instead follow someone else’s instructions on what we are supposed to (not) be seeing?

‘The famous pipe,’ wrote Magritte (Torczyner 1977: 71); ‘[h]ow people reproached me for it!’:

And yet, could you stuff my pipe? No, it’s just a representation, is it not? So if I had written on my picture ‘This is a pipe’, I’d have been lying.

Perhaps his statement brings a sigh of relief, because our eyes have not betrayed us, so long as we accept the rules of 'representation'. By engaging us in semantics, in word play, it is to these rules of representation that the artist invites his viewers to attend.

Our anxiety about the image is not entirely dispelled, however. This is not a real pipe, but rather a visual reproduction of one. Certainly, since our brain is capable of registering the difference between the two (i.e. nobody in their right mind would try to smoke the image of a pipe), it can be a pipe for us after all. Even Magritte himself refers to [his] ‘pipe’ (‘could you stuff my pipe?’)—he does not qualify it as ‘the representation of my pipe’. Yet the core of images is treacherous—while telling us the truth they also lie to us.

How might we compare the 'treachery' we witness in this painting with Judas’s act? The disciple uses a kiss—normally indicative of affection and endearment—to betray Jesus. In other words, it is a display that undermines what it seems to represent. We are left mentally to supply the words: 'this is not a kiss'.

References

Barron, Stephanie, et al. 2006. Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art / Ludion)

Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2018. ‘Sight and the Byzantine Icon’, Equinoxonline 2.1: 46–67

Torczyner, Harry. 1977. Magritte, Ideas and Images, trans. by E. Miller (New York: Harry N. Abrams)

Wear, Delese, and Joseph Zarconi. 2010. ‘The Treachery of Images: How René Magritte Informs Medical Education’, Journal of General Internal Medicine 26.4: 437–39

Unknown Byzantine artist

The Betrayal of Christ, 1439–40, Mural, Church of the Archangel Michael, North Wall, Kamiliana (Kissamos), Chania, Crete; Photo: Angeliki Lymberopoulou

Kiss and Tell

Commentary by Angeliki Lymberopoulou

The Betrayal forms part of the iconographic cycle of the Life of Christ in the programmes of monumental Byzantine decoration. The present scene is located on the island of Crete, in the eastern Mediterranean, which at the time of its creation was under Venetian domination (1211–1669 CE), a rule which proved beneficial for the erection of Orthodox churches especially in its rural parts.

The two main protagonists, Christ and Judas, are placed in the centre of the scene. Judas approaches Christ from the left, his great haste visually communicated by the wide stride he takes to reach his master. He puts his right hand on Christ’s left shoulder and is about to kiss him. Christ tilts his head towards his betrayer, to facilitate the kiss's delivery. He is standing in the middle of the scene, holding a closed scroll in his left hand and is blessing with his right hand. Christ’s serenity reflects the fact that earlier in the garden of Gethsemane he accepted his imminent fate.

Judas and Christ are surrounded by soldiers, following the narrative of John (18:3) who mentions that the disciple was accompanied by Roman soldiers with weapons and lights against the dark. The artist has depicted the soldiers dressed in a contemporary Western armour, with which he would have been more familiar, and this has the added effect of bringing the scene into the artist’s present.

They all hold spears and the soldier standing first on the right carries a flaming torch. The soldier standing directly behind Christ, also to the right, places both his hands on Christ, which signifies His arrest (Matthew 26:50; Mark 14:46). At the lower right, Saint Peter has pinned Malchus—the High Priest’s servant—to the ground and has placed his knife on the servant’s ear, while the latter tries to prevent its inevitable cutting off with his left hand.

Despite its paramount importance in Christ’s life cycle, the scene exudes a ‘calmness’ further reflected in the muted brown tones of its palette. And just as calmness precedes a storm, this treacherous Betrayal is the introductory act to Christ’s forthcoming Passion.

References

Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2006. The Church of the Archangel Michael at Kavalariana: Art and Society on Fourteenth-Century Venetian-dominated Crete (London: Pindar Press), pp. 71–75

Anthony van Dyck :

The Betrayal of Christ, c.1618–20 , Oil on canvas

René Magritte :

The Treachery of Images (This is Not a Pipe), 1929 , Oil on canvas

Unknown Byzantine artist :

The Betrayal of Christ, 1439–40 , Mural

The Betrayal

Comparative commentary by Angeliki Lymberopoulou

The Betrayal of Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane is a pivotal moment that marks the beginning of His Passion. Not surprisingly, it is narrated by all four Evangelists: Matthew 26:47–56; Mark 14:43–52; Luke 22:47–53; John 18:1–11. John is the only Evangelist who does not explicitly mention Judas’s kiss; the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) refer to this incident which became the main focus of the visualization of the episode, as both examples here, by the anonymous Byzantine artist and Anthony van Dyck, demonstrate.

Another important detail in the iconographic development of the scene is the representation of St Peter cutting off Malchus’s ear. While all four Evangelists refer to this episode, only John (18:10–11) mentions the two participants by name. Meanwhile Luke adds his own detail, describing how Christ healed Malchus after Peter’s assault (Luke 22:51). This act reflects the importance of forgiveness in the Christian faith, and while the incident is not explicitly depicted, in Byzantine art it is implied by Christ’s blessing gesture in the general direction of the high priest’s servant.

As for the people present at Christ’s Betrayal, depictions of the scene typically include either a crowd (Matthew 26:47; Mark 14:43), or a crowd with priests and generals (soldiers) (Luke 22:52), or soldiers (John 18:3), or a combination of these. At the same time, representations of the Betrayal seem invariably to gloss over the detail of a naked man running wrapped in a sheet, as mentioned in Mark 14:51–52.

The undisputed focus of this particular iconographic narrative is the treacherous kiss delivered by Judas, an act that has become synonymous with the concept of ‘betrayal’ itself. Arguably, Judas is probably the most hated figure in Christianity: Dante Alighieri in his Inferno placed him in the worst and deepest ninth circle of hell. Byzantine art depicts Judas in the arms of Satan burning in hell, while in certain parts of modern Greece it is customary to burn in the streets an effigy of Judas on Good Friday evening—probably echoing the eternal flames of the underworld in which he is imagined to reside.

While Judas’s act is morally condemnable, it should be noted that his Betrayal marks the beginning of Christ’s Passion—in short without Judas’s Betrayal there is no salvation. This is a notion that the Greek author Nikolaos Kazantzakis explored in his book The Last Temptation of Christ, written in 1955 (which was turned into a film by the director Martin Scorsese in 1988). And, just as in Van Dyck’s painting, Andrew Lloyd Weber and Tim Rice in their famous 1970 rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar (for which they produced the music and lyrics respectively) place Judas in the centre of the action by putting him in charge of the narrative. The possibility should, perhaps, be considered that Judas earned a place in hell not because he betrayed Christ, but because he did not repent—he did not ask for forgiveness and instead committed suicide, regarded by the Church for much of its history as an inexcusable sin.

Equally, the ‘treachery’ of René Magritte’s pipe encourages pause for consideration and alternative thinking, albeit in a different arena that explores the relation between visuality and semantics. A representation of a pipe is not an ‘actual’ pipe—but is it really wrong to call it a pipe without further qualifications? To complicate things even further, the Byzantines believed that all representations of saints and saintly events reproduced an original work made from real life and hence channelled devotion to the real saints and/or feasts. It is true that, as Magritte claims, the image of a pipe does not and cannot function as the actual object itself (i.e. it cannot be used for smoking). But in a hypothetical universe where actual pipes had (for inexplicable reasons) become extinct, their representation would then be the closest to the real object one could get.

Magritte’s painting does not distort the image of a pipe and, probably, it is where its treachery lies: we are sure of what we see but we are told it is not true. By revisiting the evidence, we comprehend that by qualifying the nature of the treachery we can understand it, accept it, and reconcile with it. Perhaps in a similar manner a faithful person can eventually understand and be reconciled to Judas’s Betrayal, since it leads to salvation.

Viewed this way, not even treachery is safe from betrayal. Betrayal itself is betrayed by something even greater in the story of salvation.

References

Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2020. ‘Hell on Crete’, in Hell in the Byzantine World. A History of Art and Religion in Venetian Crete and in the Eastern Mediterranean, vol. 1: Essays, ed. by Angeliki Lymberopoulou (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 137–40

Commentaries by Angeliki Lymberopoulou