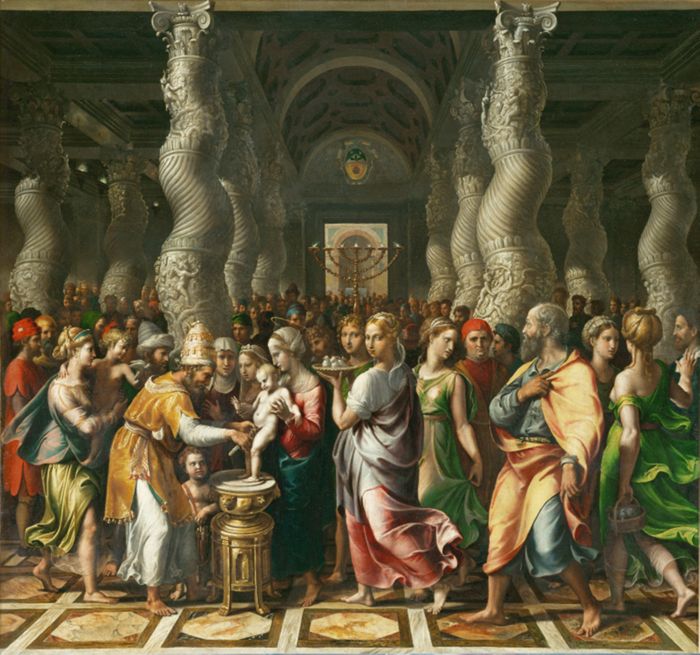

Andrea Commodi

Fall of the Rebel Angels, 1612–14, Oil on canvas, 170.69 x 182.88 cm, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence; 00123769, Scala / Art Resource, NY

Defiling Passion and Despising Authority

Commentary by Sarah C. Schaefer

Around 1616, Andrea Commodi secured a commission for the end wall fresco of the Cappella Paolina in the papal Quirinal Palace. Enraptured by the works of Michelangelo (and acquainted with the Buonarroti family), Commodi prepared a design that would rival the master’s Last Judgement. Although the fresco was ultimately abandoned, a number of studies remain, including two pen and ink drawings now in the British Museum, and this elaborate preparatory painting.

The subject Commodi chose represents both a significant connection to and also a departure from Michelangelo’s work, which itself was unorthodox. The Last Judgement incorporates both the damned and the saved (in adherence to iconographic tradition), but, importantly, the bodies of members of both groups are heroically muscular (as opposed to the emaciated forms of the damned one often finds in medieval tympana).

The fate of the angels who joined Satan’s rebellion is mentioned several times in the New Testament (see Revelation 12:7–9; Matthew 25:41; 1 Corinthians 6:3; Jude 1:6). They are only mentioned in passing here in 2 Peter 2:4. But the allusion is unusual in its lack of reference to Satan himself, as the agency of the rebel angels is generally conflated with that of their master. Although this painting represents only a fraction of the intended final work, the isolation of the angels from any narrative surrounding may perhaps be significant, seeming to have much in common with 2 Peter 2. The fallen angels maintain their heroic, idealized nude forms, much like the sinful people being dragged into the hellmouth at the lower right of Michelangelo’s fresco. The musculature of the angels’ bodies is made all the more palpable through their representation in grisaille, a painting technique that employs a monochromatic palette and enhances the sculptural qualities of the objects depicted. And, notably, Satan is not represented in this visual scheme—nor is there any divine figure doling out judgement. We are witness only to the writhing, contorted, despairing forms of those who followed the deceiver.

This underscores the consequences of succumbing to earthly desires, particularly those who, according to Peter, ‘indulge in the lust of defiling passion and despise authority’ (2 Peter 2:10).