Luke 2:21

The Circumcision of Jesus

Federico Barocci

The Circumcision, 1590, Oil on canvas, 356 x 251 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris; MI 315, Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Circumcision/Circumvention

Commentary by Itay Sapir

Federico Barocci’s work is an exemplary product of the Counter-Reformation’s precepts for effective art: his paintings are accessible, intimate, and sweetly emotional, so that Catholic teachings are mediated through them to broad audiences.

The circumcision of Christ, in the representation by the painter from Urbino, is celebrated as a family event, and the special guests—shepherds and proto-baroque flying angels—are no strangers either but belong to the family circle.

And so do we, the prospective viewers (initially in the oratory in Pesaro for which the altarpiece was created). The composition invites us to approach, and our full attention to the ritual operation is expected, ideally modelled on the concentration of those represented within the painting.

Everything is characteristically soft and fluffy in this scene: there is no architecture properly speaking, and a landscape, seen through the opening of a theatrical curtain, opens up behind what seems to be a grotto where the figures are located. The baby Jesus is veritably babylike, if slightly too self-conscious for his age, as he intently looks us in the eye. The men surrounding him are tender and careful rather than solemn and intimidating. They wear no official garb and the one seemingly responsible for the circumcision itself is unceremonially bareheaded.

Barocci ingeniously circumvents the potential seriousness, not to mention bloody painfulness, of the circumcision—which doesn’t mean that sophisticated religious concepts are not conveyed in the process. Judith W. Mann notes that on the left, ‘an acolyte gestures toward the foreskin that floats in the bowl in the table, lined up with the trussed lamb so that its symbolic association with Christ’s eventual sacrifice is made clear’ (Mann 2012: 17), and that the still life in the bottom right corner is not only a precious effet de réel but also a reference to the eucharistic meal, ‘appropriate since both body and blood are associated with the Circumcision’ (ibid 18).

References

Mann, Judith W. 2012. ‘Innovation and Inspiration: An Introduction to Federico Barocci’, in Federico Barocci. Renaissance Master of Color and Line (New Haven: Yale University Press)

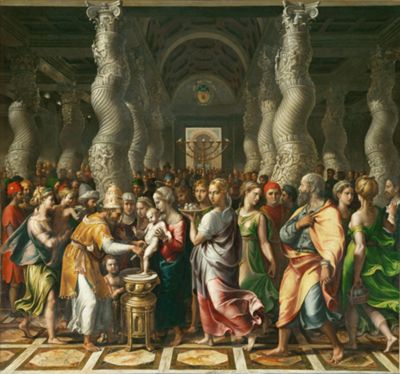

Giulio Romano

The Circumcision, 1520–24, Oil on canvas (transferred from panel), 115 x 122 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris; ancienne collection royale/de la Couronne, INV 518 ; MR 304, Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Circumcision/Circumnavigation

Commentary by Itay Sapir

Giulio Romano’s painting, while relatively small, is a typical example of the excess attributed to the generation following the High Renaissance ‘Great Masters’ (Giulio was Raphael’s most talented assistant). The classical ‘infrastructure’ is still there, competently mastered, but its economy is subtly—and sometimes blatantly—undermined. The image seems vaguely symmetrical but is, in fact, quite unbalanced; the architecture is similar in principle to classical examples, while including destabilizing elements, the most prominent of which are the twisted columns, soft and wavy where such elements should have been hard, rigid, and static (Tafuri 1989). A characteristic Renaissance interest in the ‘socialisation’ of biblical scenes—the insertion of almost any episode in a broader social context—is also here brought to an extreme.

Indeed, the composition is exceedingly crowded. The community into which circumcision and naming mark entry seems well represented. However, the event remains symbolic rather than concrete: most people present at what is depicted as the Temple (although the New Testament does not specify this is the location for Jesus’s circumcision) don’t pay attention to the momentous occasion. Giulio drowns the circumcision in an ocean of faces (mostly repetitive), graceful movements, and ornamental elements, so that the viewer must navigate a complex space in order to decipher the image. The empty space in the foreground adds a theatrical aspect without alleviating the impression of frenetic saturation.

Another aspect one could easily attribute to Giulio’s ‘Mannerist’ style is the representation of Jesus himself, replete with naturalistic details but also oddly artificial. Instead of a human newborn, we see a young child standing: sculptural, somewhat solemn, and seemingly fully conscious of the ceremony’s meaning.

This is somewhat counter-productive theologically: the representation of the circumcision, and the visibility of Christ’s genitals more generally, were important precisely for the demonstration of the baby’s fully human nature. Not surprisingly, painters of Giulio’s generation were often accused of ignoring doctrinal truth in the interest of showing off their artistic virtuosity and originality.

References

Tafuri, Manfredo. 1989. ‘Giulio Romano: linguaggio, mentalità, commitenti’, in Giulio Romano (Milan: Electa)

Andrea Mantegna

Presentation of Christ at the Temple, 1460–65, Tempera on wood, 86 x 43 cm, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence; 1890 no.910, Scala / Art Resource, NY

Circumcision/Circumference and Precision

Commentary by Itay Sapir

Andrea Mantegna’s panel—one of the earliest depictions of Christ’s circumcision as the principal subject of a work—was probably part of an ensemble containing, among other scenes, The Adoration of the Magi and The Ascension. Within the composition, the ceremony is fused with another event from Jesus’s early life, the presentation in the Temple, to which the turtledoves in Joseph’s basket traditionally refer.

The most striking aspect of the painting is its painstaking precision of detail and the sculpture-like limpidity of every form’s contour. While stylistically this is wholly in line with the artist’s usual practice, here this astonishing quality is also echoing the more unusual subject matter: Mantegna’s artistry is evidently comparable to the skill and concentrated attention needed for the delicate operation of circumcision. Indeed, the priest, who has just completed his task and recoils to examine its success, holds his knife just as a painter would his own brush when stopping to observe his progress between brushstrokes.

However, whereas the priest removes skin in an act of subtraction, the painter is a quasi-miraculous creator who adds something new to the world.

The ‘Renaissance’ character of the composition is obviously visible in its interest in the archeologically correct representation of the architecture of the space, of the reliefs (whose content—the Sacrifice of Isaac and Moses with the Tablets of the Law—is necessarily Old Testament and typological rather than pagan), and of the garments worn by his figures.

But more profoundly, Mantegna develops here another constant aspect of Quattrocento Italian art: the placing of any narrative scene within the context of society, in a community. Here, this is done minimally but efficiently through the inclusion of the three figures on the right, standing behind Mary and the Christ Child. For Leo Steinberg, the anonymous mother’s gesture, ‘averting her little boy’s face to spare him a painful sight’ (Steinberg 1996: 50–52), also has a theological import—by indicating to her son ‘Not for you’, writes Steinberg, she reminds Christian viewers that thanks to Christ’s blood—shed already at a tender age—there is no more need for them to go through that ordeal themselves.

References

Steinberg, Leo. 1996 [1983]. The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press)

Thiessen, Matthew. n.d. ‘Gentile Circumcision’, Bible Odyssey, available at https://m.bibleodyssey.org/articles/gentile-circumcision/ [accessed 15 January 2025]

Federico Barocci :

The Circumcision, 1590 , Oil on canvas

Giulio Romano :

The Circumcision, 1520–24 , Oil on canvas (transferred from panel)

Andrea Mantegna :

Presentation of Christ at the Temple, 1460–65 , Tempera on wood

Ceremony, Party, Intimacy

Comparative commentary by Itay Sapir

One could easily—and without doubt interestingly—tell the story of these three pictorial representations of Christ’s circumcision as exemplary of the artistic evolution of early modern art. In 150 years, Italian painting evolved from a severe but harmonious Renaissance aesthetic, evidently reworking classical references (Andrea Mantegna), through Mannerist horror vacui and playful artifice (Giulio Romano), all the way to proto-Baroque emotionally charged spectacle (Federico Barocci).

However, in light of the specific subject matter, implicating the integration of a newly born person into a community, it would be even more rewarding to visually trace the differences in the three historical moments’ conception of the relation between individuals and societies. The single verse these paintings translate into images includes two aspects of a newborn’s entry into collectivity: the physical marking of the circumcision, but also, less simple to visually depict, the naming of the new community member.

Moreover, the identity of the young boy adds many more layers of meaning to the ritual: as Leo Steinberg demonstrates in his groundbreaking, now classic The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion (1983), theological discussions of Jesus’s genitals, and particularly of the ceremony in which they take centre-stage, abound. The Christian approach to circumcision is an intricate combination of reverence, acceptance as a historical inevitability, rejection, and disgust, and the paintings—quite rare—depicting the scene as a principal subject had to navigate their way through all these contradictory reactions. Show and hide, repress and celebrate; artists were obliged to negotiate the delicate balance between redemption and what might have seemed to them like mutilation; bloodletting and cleansing; the spiritual and the basely physical.

These three painters represent that important double event of naming and circumcision in three different formats, each expressing its own, diverse spirit: as a solemn ceremony, as a crowded festivity, and in the guise of a warm family gathering. The setting of Mantegna’s Presentation in the Temple, also representing Christ’s circumcision, is monumental, its verticality somewhat dwarfing the figures, emphasizing how the meaning of what is being ritually done to Christ exceeds the horizons of any one individual. The Paduan painter includes a small representation of what we would now call ‘civil society’ in this otherwise minimalist representation, in order to remind us that the circumcision is not only a seal of relationship between God and an individual person, but also the business of society at large.

Giulio Romano also diminishes the protagonists’ scale, although he does so not by comparison with the surrounding architecture but by making the holy family and the priest just one group amidst a huge crowd. The humility of God’s son joining the community of mortals is thus foregrounded, counterbalancing Jesus’s appearance—quite distinct from that of an ordinary eight-day-old baby. Giulio also reminds us that the circumcision, perhaps in parallel to baptism (the Christian equivalent more familiar to his audience), is a festive event—there are gifts presented and even bodily movements reminiscent of dancing. As the only one of the three artists choosing to depict the bloody and painful circumcising act taking place, the knife concretely touching Christ’s foreskin, Giulio might have thought that the inclusion of a joyful crowd, seemingly oblivious to the reality of the act, would be reassuring for the viewers.

After the upheavals of the mid-sixteenth century—Reformation, Counter-Reformation, and wars of religion—both theological niceties and frenetic partying seemed anachronistic and far from the needs of Church authorities. Barocci responds to the new situation by inventing a mode of painting as remote from Mantegna’s serious erudition as it is from Giulio’s sophisticated, somewhat futile gracefulness: an art seeking to speak directly to the heart of the faithful. Depicting the circumcision, he evokes the event’s character as an intimate, family gathering: entry into society passes first by integration into one’s kin, even if the definition of a ‘family’ is here enlarged to include anyone feeling intimately connected to the momentous event.

And who is not concerned with that specific circumcision? According to Christianity, Jesus’s shed blood did much more than signify his own belonging to the Jewish community, more even than confirming the Jews’ covenant with their God. The cutting of the baby’s flesh inaugurated the universal redemption guaranteed by God’s incarnation. Barocci’s undeniable pictorial grace is the aesthetic manifestation of divine Grace, striking when compared to Mantegna’s sub lege (‘under the law’) atmosphere, adequate for Old Testament scenes (two of which indeed appear in the lunette reliefs above), not to mention Giulio’s almost pagan carelessness.

References

Steinberg, Leo. 1996 [1983]. The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion (Chicago: The University of Chicago)

Commentaries by Itay Sapir