1 Corinthians 2

Divine Incognito

Graham Sutherland

The Crucifixion, 1946, Oil paint on board, 275 x 262 cm, St Matthew's Church, Northampton; Courtesy St Matthew's Church, Northampton

Knowing Nothing

Commentary by Clementine Kane

The Apostle Paul, eschewing the powerful rhetorical modes of his day, reiterates his simple, shocking message: Jesus Christ, crucified, is the way of life.

The starkness and simplicity of Paul’s message is reflected in Graham Sutherland’s spare crucifixion. Inspired by long meditation on Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, Sutherland’s Christ is a sharply drawn modern interpretation (Newton 1966: 282). The geometric abstraction describes his suffering; the measured lines constrict his body. Set against a deep blue background, the absence of any other figures or reference suggests an atemporal quality to this event. Outside of a particular time, it can speak to all times.

Despite the extreme angles of his arms, Christ’s body does not sag under its own weight but is suspended between heaven and earth. His body is still and collected, his arms stretched out for the love of the world. Yet, the intensity of his experience is marked in his clenched face and the spearhead of his sharply drawn ribcage, which seems to emphasize the agony of each breath.

But this is a meditation not on suffering but on suffering with—compassion—that marks the intersection of the human and the divine in the Christian tradition. Paul, being confirmed to his Lord, also embodies compassion:

And I was with you in weakness and in much fear and trembling. (v.3; emphasis added)

Paul does what leaders are so often unable to do and admits his own weakness, his fear, and his reliance on something greater than himself.

As a Roman Catholic convert in twentieth-century England, Sutherland was confronted with the severe realities of the Second World War and was no stranger to the struggles of the Christian faith. The convergence of brutal suffering and spiritual struggle seems also to be a defining feature of Grünewald’s grim work in its inspiration of Sutherland’s painting. It was only in deep contemplation of the Isenheim figure that Sutherland could alchemize the fear and suffering of his generation into a crucifix for the twentieth century—as, perhaps, for any time in need of a God who ‘suffers with’.

References

Davies, Hugh and Horton Davies. 1978. Sacred Art in a Secular Century (Collegeville: Liturgical Press)

Kistemaker, Simon J. 1993. Exposition of the First Epistle to the Corinthians (Grand Rapids: Baker Books)

Newton, Eric and William Neil. 1966. 2000 Years of Christian Art (New York: Harper & Row)

Unknown artist

Sophia, Wisdom of God, c.1625, Tempera and gold on panel, 61 x 65 cm, The Museum of Russian Icons, Clinton, MA; Icon Museum and Study Center, Clinton, Massachusetts USA

A Spirit of Wisdom

Commentary by Clementine Kane

The Apostle Paul longs for his community to be spiritually mature and filled with the wisdom of God. This wisdom is both revealed by the Spirit of God and an inherent part of God, a relatedness that is evoked in the icon of Sophia, the Wisdom of God.

Sophia (Greek: ‘wisdom’) is neither an angel nor a saint, but rather the personification of an attribute of God. This icon, of the Novgorod ‘Angel of the Lord’ type, dates from the sixteenth century (Fiene 1989: 457). The figure of Wisdom is enthroned, winged, and crimson hued. On either side, forming a deësis, Mary holds the Christ Child and John the Baptist presents a scroll. Christ Pantocrator (Ruler of All) presides over the figure of Wisdom and above him angels unfurl the banner of the starry cosmos beneath an empty throne, an apophatic representation of God the Father.

The question of who or what ‘Sophia’ is has elicited varying answers throughout Christian history. Often Sophia is identified with the preincarnate Christ, the divine Logos ‘[through whom] all things were made’ (John 1:3). The Russian Orthodox theologian Sergei Bulgakov suggests that the figure of Sophia represents something deeper, the very oneness of God in which the three persons are united (Bulgakov 2008: 107). Another view, espoused by early Church Fathers such as Irenaeus of Lyons (c.130–202 CE) and Theophilus of Antioch (died c.183 CE) held that Sophia was a manifestation of the Holy Spirit.

The icon of Sophia, the Wisdom of God, does not clearly correspond to any of these three interpretations, but makes an enigmatic contribution to the body of art, literature, and philosophy around the figure of Sophia. The Spirit of Wisdom is complex: intimately a part of God who ‘searches everything, even the depths of God’ (1 Corinthians 2:10), and yet also the gift of God to his children.

Though the core of Paul’s message is simple, his ensuing teachings expand in complexity and require spiritual maturity to apprehend. In like manner, this icon yields a constellation of meanings, speaking differently to different viewers who must use wisdom to interpret it.

References

Bulgakov, Sergius. 1993. Sophia, The Wisdom of God: An Outline of Sophiology (Hudson: Lindisfarne Press)

______. 2008. The Lamb of God. (Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans)

Fiene, Donald. 1989. ‘What is the Appearance of Divine Sophia?’, Slavic Review, 48.3: 449–76

Florensky, Pavel. 1997. The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: An Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Schipflinger, Thomas. 1998. Sophia-Maria: A Holistic Vision of Creation (York Beach: Samuel Weiser)

Unknown artist

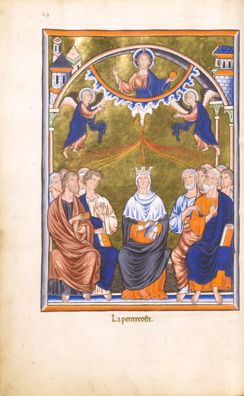

Pentecost, from the Ingeborg Psalter (Psalterium Ingeburgae reginae), c.1193, Parchment, 300 x 200 mm, Bibliothèque du château, Musée Condé, Chantilly; Ms 9/1695 f.32v, Image courtesy of Bibliothèque numérique de l'IRHT

The Mind of Christ

Commentary by Clementine Kane

An image of the Spirit descending at Pentecost articulates in concrete terms the more abstract ideas of 1 Corinthians 2. In this page from an illustrated thirteenth-century psalter, we see the disciples assembled around Mary as the Spirit descends. The book was produced in France for Ingeborg, the Danish wife of the French king Phillip II (Deuchler 1970: 57). In this version, Mary is rendered as a crowned medieval noblewoman, perhaps modelled on Ingeborg herself.

The disciples, subtly individualized, respond with gestures rather than facial expressions to the event unfolding above and through them. Crimson streaks flow to each head from the throat of a haloed dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit. The dove itself bears a cruciform halo as if to underscore the connection between God the Son and God the Spirit.

Christ presides over the bestowal of the Spirit—the gift of his ongoing presence to believers. The figure of Christ is situated both within the architectural space of the room and beyond it, as delineated by an orange crescent and undulating blue emanations. He is the source of the gifts given by the Holy Spirit, although his image is a surprisingly rare inclusion in the imagery of Pentecost.

In the final verses of this chapter, Paul unites the two themes he has introduced—the startling simplicity of his message and the need for mature spiritual wisdom granted by God. To receive the gifts of the Spirit of God is to acquire the ‘mind of Christ’ (1 Corinthians 2:16). For Paul, each person needs the indwelling of the Spirit to understand the things of God; without this infusion, Jesus’s death is ‘a stumbling block’ and ‘folly’ (1:23).

The moment of Pentecost pictured in this manuscript is the moment of the bestowal of the ‘mind of Christ’. Although the figures are rendered in a way that reflects the context of the work’s patroness, the golden background sets this scene apart from any particular time and space, perhaps emphasizing the availability of this spiritual transformation both to the first followers of Christ and the viewers of the manuscript.

References

Deuchler, Florens. 1970. ‘The Artists of the Ingeborg Psalter’, Gesta, 9.2: 57–58

Commentaries by Clementine Kane