Micah 1–3

‘To the Edge of Doom’

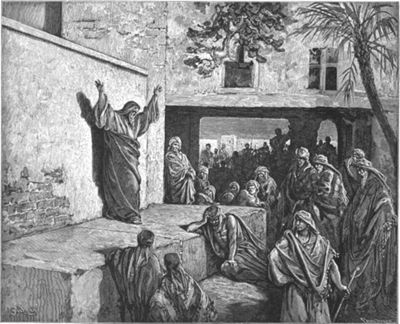

Gustave Doré

Micah Exhorting the Israelites to Repent, from Dore Bible, 1866, Engraving; Internet Archive

‘This Portentous Figure’

Commentary by Allen Dwight Callahan

This work by the French painter, illustrator, engraver, caricaturist, and lithographer Gustave Doré appears in Doré’s illustrated Bible, published in 1865. Its representation of the prophet is the visual antithesis of the silent, bedridden Micah in the medieval manuscript illumination elsewhere in this exhibition: here, Micah has forsaken the boudoir for the public square. He speaks, standing up, fully clothed, both arms extended upward, imploring the people’s attention.

This is indeed how the Bible remembers Micah being remembered in the prophet Jeremiah’s day.

And some of the elders of the land arose and said to all the assembled people, ‘Micah of Moresheth, who prophesied during the days of King Hezekiah of Judah, said to all the people of Judah: “Thus says the Lord of hosts, Zion shall be plowed as a field; Jerusalem shall become a heap of ruins, and the mountain of the house a wooded height”’.(Jeremiah 26:17–18)

Micah is a prophet against prophets. The figure of the prophet, along with that of the prince and the priest, comprise the troika of corrupt elites that Micah vehemently indicts (Micah 3:11). Like Jeremiah a generation later, Micah decried prophecy at a time when the motive of the prophet had become fatally corrupted by the profit motive.

And, like Jeremiah, Micah prophesies to mixed reviews. The audience in Doré’s engraving suggests a varied reception: some in the crowd appear to be pensive; others, anguished; yet others, annoyed. At lower right, a man attends to Micah’s rant, but his body language speaks of his ambivalence: though he glances back in the prophet’s direction, his torso is turned forward, and, in mid-stride with staff in hand, he appears to have other places to go and other things to do.

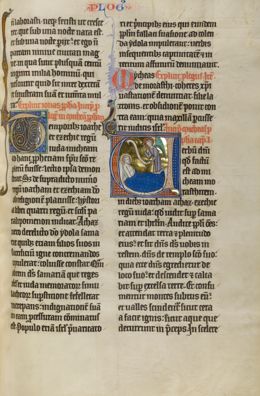

Unknown Franco-Flemish artist

Initial V: An Angel before Micah, c.1270, Tempera colours, black ink, and gold leaf on parchment, Leaf: 47 x 32.2 cm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Ms. Ludwig I 8, v2 (83.MA.57.2), fol. 183, Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program

‘When the Sun Sets, Who Doth Not Look for Night?’

Commentary by Allen Dwight Callahan

In this illumination from a magisterial thirteenth-century Vulgate Bible, the initial moment of prophetic vocation is framed by an enlarged ‘V’. It is the first letter of verbum, the first word of Micah 1:1 in the Latin translation: Verbum Domini quod factum est ad Micham Morasthiten (‘The Word of the LORD that came to Micah the Morasthite’).

The scene features a bedside revelation: apparently, the Word has come unbidden, disturbing Micah’s peace. The prophet has turned in for the evening; his posture suggests he was sleeping, or at least trying to sleep. At left, he reclines, naked to the waist, partially covered in blue bedclothes, a white sheet across his torso, his forearms buried in his blanket.

The prophet is mute: his mouth is shut. But his eyes are open. Though he is poised for slumber, Micah’s expression nevertheless shows that he is quite awake. His body is covered, but his face—the window of the mind—is wide open.

At right, a winged angel, standing and slightly bent in Micah’s direction, beckons with the upturned index finger of his right hand. In his left hand, a scroll unfurls its full length in the curved shape of an inverted ‘S’ that bisects the space between him and the prophet. The scroll is unmarked, a roll of blank vellum: not a letter is written upon it.

Though biblical prophecy has become Scripture, in the beginning it was not so: we can read the bare scroll here as signifying that revelation comes to the prophet as something unscripted. The scroll serves as the sign that prophecy ‘happens’, that revelation is not ‘content’ but event, translating into sounds and signs those flashes of divine insight that the Bible calls ‘the Word of the LORD’.

Unknown Assyrian artist

Sennacherib Watches the Capture of Lachish, 700–692 BCE, Gypsum wall panel, 251.46 x 177.80 cm, The British Museum, London; 1856,0909.14, Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

‘Doomsday with Eclipse’

Commentary by Allen Dwight Callahan

This wall relief from the South-West Palace at Nineveh, the imperial capital of the ancient Assyrians, depicts the procession of prisoners after the capture of the Judahite city of Lachish by the Assyrian army in 701 BCE. Two Assyrian soldiers, marked by their characteristic conical helmets, force several hapless Lachishite prisoners forward, some of whom are prostrating themselves before the Assyrian king, Sennacherib, at centre, flanked by two royal servants bearing feather fans.

The reliefs on these slabs originally formed a single, continuous work, measuring 2.4 metres high and 24.4 metres wide, that covered the inner walls of the royal chamber. They vividly depict Sennacherib’s victory over the fortified city. This crushing invasion of the Assyrian army is only suggested in 2 Kings 18:13–15, the Bible’s sketchy account of the event.

These monumental stone portraits of mayhem, abject humiliation, and mass destruction covered the inner walls of the imperial court, serving as the grisly, oversized decorations of an Assyrian-style royal interior that literally surrounded the monarch as he sat on his throne. The reliefs were an indoor billboard advertising the bloodlust and cruelty of Assyria’s imperial military might.

According to Micah, this very bloodlust and cruelty would soon strike Jerusalem as a divine rod of reproof to chasten Judah’s venal, greedy elites: ‘Therefore because of you [rulers of the house of Jacob and chiefs of the house of Israel], Zion shall be plowed as a field; Jerusalem shall become a heap of ruins’ (3:12).

But it wouldn’t. And it wasn’t. And it didn’t. The books of Chronicles recap Sennacherib’s threat to attack Jerusalem: but pace Micah, the city was miraculously spared the fate of Lachish, and was left, for the moment at least, in peace (2 Chronicles 32:9–11).

Gustave Doré :

Micah Exhorting the Israelites to Repent, from Dore Bible, 1866 , Engraving

Unknown Franco-Flemish artist :

Initial V: An Angel before Micah, c.1270 , Tempera colours, black ink, and gold leaf on parchment

Unknown Assyrian artist :

Sennacherib Watches the Capture of Lachish, 700–692 BCE , Gypsum wall panel

‘Warnings, and portents, and evils imminent’

Comparative commentary by Allen Dwight Callahan

The Word of the LORD that came to Micah the Morasthite…

That’s it. No mention of Micah’s father, clan, or profession. We are merely told that he is from Moresheth, a town in the Judean lowlands, the rural periphery for which Jerusalem was the urban centre. The only thing the book of Micah tells us about its namesake is that he is from the countryside. He is a peasant, a rustic. A hick.

This Morasthite hick, who appears at the source and origin of classical Hebrew prophecy, never refers to himself as writing anything, nor is he remembered as having written the oracles that now constitute the book that bears his name. Micah is imagined in the book of that accomplished litterateur, the prophet Jeremiah, as every bit the plaintive principal of Gustave Doré’s engraving—haranguing his audience, but not writing to them.

Though his words have come down to us written on a scroll, Micah expressed himself in the spoken word. His métier is that of Orpheus and Muhammad. Micah is not a writer. He is a rapper, albeit quite ‘old school’. He does not write lines: he ‘spits rhymes’, as it were.

Yet Micah the man comes to be effaced by Micah the book. It is only in the first three chapters of that book that we come close to Micah the man, depicted in the Vulgate illumination as an insomniac to whom the Word of the LORD comes in the night, delivered by a winged angel.

The Latin Vulgate has captured the force of the original Hebrew: Verbum Domini quod factum est ad Micham = Yahweh ašer hāyāh ‘el Mîkāh; literally, ‘The Word of the LORD, which happened to Micah’. The Word is uncanny, unpredictable, an event that Lloyds of London would have formally referred to as an ‘Act of God’. The prophet’s vocation is not his volition; it is not something that he has sought, but something that has sought, and found, him. It invades his privacy—that still, small voice that comes to rob him of his rest.

Prophecy, the message of the prophet, is not his own. Or at least, that disclaimer must be his claim: the prophet’s lips move, but it is God who speaks—God, that Great Ventriloquist in the Sky. As the hand puppet of the LORD, whatever the prophet says is what the LORD says (Micah 2:3; 3:5).

Later ages would remember Micah’s prophecy as both repudiated and vindicated.

Repudiated, because the books of Chronicles would claim that God answered the prayers of King Hezekiah and his court prophet, Isaiah, by restraining Sennacherib from doing to Jerusalem what he did to Lachish (2 Chronicles 32:20–22). The Chronicler thus suggests that the tardy piety of a couple of contrite elites could forestall the justice due a society that allowed its ruling class to eat its impoverished masses alive (Micah 3:3).

Vindicated, because the Babylonians, the imperial successors to the Assyrians, would ultimately wreak upon Jerusalem the catastrophe gruesomely depicted in the Lachish Relief, consigning its princes, priests, and prophets to the dustbin of history.

But the elites would exact a posthumous revenge. Micah’s oracles would come to be curated by the descendants of the very class they came into existence to condemn, and the book of Micah would thereby become an heirloom of its despised heirs.

Modern scholars argue that later revanchist redactors have interpolated the following prophecy of divine restoration— so incongruous with his outrage — into Micah’s oracles of judgement:

I will surely gather all of you, O Jacob, I will gather the survivors of Israel; I will set them together like sheep in a fold, like a flock in its pasture; it will resound with people. The one who breaks out will go up before them; they will break through and pass the gate, going out by it. Their king will pass on before them, the Lord at their head. (Micah 2:12–13)

It is those ancient, anonymous custodians of Micah’s oracles—oracles written on a long scroll, along with other oracles that he could not have spoken let alone written—who have written into Micah’s denunciations this grandiose post-exilic promise to Make Israel Great Again.

References

Cuffey, Kenneth H. 2015. The Literary Coherence of the Book of Micah: Remnant, Restoration, and Promise, LHBOTS (London: T&T Clark)

Jacobs, Mignon R. 2006. ‘Bridging the Times: Trends in Micah Studies since 1985’, Currents in Biblical Research 4.3: 293–329

Wagenaar, Jan A. 2001. Judgement and Salvation: The Composition and Redaction of Micah 2–5, Vetus Testamentum, Supplements, vol. 85 (Leiden: Brill)

Commentaries by Allen Dwight Callahan