Hosea 14

Gardened By God

Hans Wertinger

Summer, c.1525, Oil on panel, 23.2 x 39.5 cm, The National Gallery, London; Bought, 1997, NG6568, © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

Rendering the Fruit

Commentary by Elena Greer

Hans Wertinger uses confident, curling brushstrokes to imbue this rustic scene with the vibrancy of nature at the height of summer. The trunk of a sinuous tree reaches energetically beyond the confines of the picture’s fictive frame. A shepherd takes advantage of its shade to shear his sheep—the only moment of calm in this animated painting. Men waist-high in grasses vigorously scythe them for hay. A woman with a tray of fruit on her head makes her way out of the picture to market.

Wertinger uses the broad arc of a wide river to lead our eye to the range of mountains in the background and beyond as it continues its journey through the valley, curving round the conifer-studded slopes.

Pinpointing the birth of landscape painting in its own right is not straightforward but Wertinger’s images and those of his German contemporaries such as Albrecht Altdorfer (shortly before 1480–1538) began to make landscapes an increasingly dominant feature of their religious and subject paintings. In this image, landscape is the vehicle of the subject: summer itself.

Wertinger’s image derives from the illuminations of individual months and seasons found in medieval Books of Hours, which regulated Christian worship daily, monthly, and annually. These so-called ‘Labours of the Month’ charted the manual work associated with each month and/or season. Interleaved with the ordained devotions of the Christian year, religious worship and the cycles of nature were inextricably linked. Accompanied by depictions of autumn, winter, and spring, images like this often decorated domestic interiors—for example, in friezes running around the upper part of a room.

The relationship between the figures and the land they cultivate according to its internal rhythm of birth, fruition, and decay is key to this picture’s meaning. The landscape is not simply an abstractly beautiful scene, but it is—as in Hosea—a depiction of the people’s connection to nature, and to God. Hosea’s language is evocative of a lush Mediterranean garden replete with lilies (14:5), olives (v.6), and cypresses (v.8).

Images like Wertinger’s ventured into a secular sphere but they contained a moral meaning: God’s abundance dictated the course of the seasons and the livelihood and pleasure of every member of society. Hosea references the fruits of the communal effort of the harvest—both those that are basic (like grain—translated ‘garden’ in the RSV) and those that are festive (like wine (v.7)).

Olafur Eliasson

Ice Watch, 2014, 12 blocks of glacial ice, Installation view: Place du Panthéon, Paris, 2015, variable; © 2014 Olafur Eliasson, Photo: Martin Argyroglo, Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles

Melting Before Our Eyes

Commentary by Elena Greer

Twelve blocks of arctic ice ranged in a circle like giant opalescent gems studding the face of a giant clock or watch appear overnight in the centre of European cities.

The artist, Olafur Eliasson, observed the reaction of passers-by to these unexpected visitors. Initially puzzled or confused—perhaps intimidated—most people were drawn towards the gleaming slabs. First, a tentative touch would cause them to flinch as though they had touched a hot stove; the first shock was just how painfully cold the ice was. Getting closer, some placed an ear to the ice, close enough to hear a gentle fizzing sound.

The ice slabs were in fact blocks of frozen glacial snow compacted over millennia, and that sound was pressure bursting millions of tiny bubbles within, releasing air that had been preserved for 15,000 years. This air, some visitors discovered, had a particular scent. The blocks were tasted too, children and adults compelled to lick the glassy surfaces.

Some people, once fully-acquainted with these alien visitors to the metropolis, wrapped their arms around them, a gesture perhaps expressing love, gratitude, or even grief, and one which, as the warmth of the body met the icy block, would cause it to melt more rapidly than before.

Like John Ruskin, whose work is elsewhere in this exhibition, Eliasson is encouraging a direct personal engagement with nature—including (from his twenty-first-century perspective) its decline.

Climate change and its impact on the arctic ice sheets is well-known but largely abstract to most people. The knowledge that Eliasson was attempting to develop with this installation was relational and experiential, not intellectual. Experiential knowledge, like that Hosea is encouraging the Israelites to acknowledge, is, according to the behavioural scientists with whom Eliasson collaborated, essential to provoking action, which is by turn essential for reducing the impact of climate change. The action called for by Hosea and Eliasson in their respective contexts requires a turn away from the perilous enticements of contemporary life.

For Hosea, such enticements alienate us from God. In Eliasson’s work one might see God present within the ice—its ancient air and water symbolizing eternity—yet this ice is visibly melting before our eyes.

John Ruskin

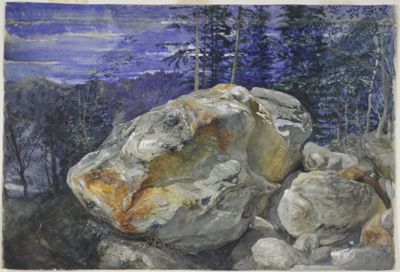

Fragment of the Alps, c.1854–56, Water colour and gouache over pencil on paper, 335 x 493 mm, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard Art Museums; Gift of Samuel Sachs, Bridgeman Images

The Divinity is in the Detail

Commentary by Elena Greer

For John Ruskin (1819–1900), as for the prophet Hosea, God revealed himself in nature, the confirmation of his creative agency.

One of the first exercises put to students in Ruskin’s The Elements of Drawing (1857) was to draw a pebble from the garden. For Ruskin—writer, educator, artist, and social critic—the study of the humblest of nature’s forms would encourage a love and intimacy with it; as he noted, ‘a stone, when it is examined, will be found a mountain in miniature’ (1874: 6.38). Therefore, when faced with the vast, majestic grandeur of the Alps—his most beloved of landscapes—the attention lavished on this single boulder was typical.

Ruskin taught—and practised—an intense scrutiny of the subject of any artwork, with all its subtle gradations of colour and light. It was translated onto paper by the minute application of the finest brushstrokes of body colour (watercolour made opaque through mixing with white). Here he has mapped the colours and patterns of the rock, its craggy edges and bulbous forms, and the effect of light and shade on its textured and rusty surface created through the oxidation of iron within.

The first four verses of Hosea 14 are a call to repentance; the Israelites are reminded of why God has turned away from them. They have made alliances with Assyria and worshipped foreign idols (v.3). Yet, unlike local fertility gods, the God of Israel is the source of the fruitfulness of the whole earth.

Hosea stresses the constancy of God’s sustaining provision—‘I am like an evergreen cypress, from me comes your fruit’ (v.8)—and provides Israel with the text for its repentance: ‘we will say no more, “Our God,” to the work of our hands’ (v.3).

This honest reflection marries with Ruskin’s attitude to looking at nature. It must be done with a purity of heart and without idolization of one’s own ‘artistry’. He warned his readers: ‘you will never love art until you love what it mirrors better’ (1872: 45).

Art, created by humans, is artifice unless it has a spiritual foundation: the perception of nature as the manifestation of the divine. Ruskin’s call for a deep personal relationship with nature reflects Hosea’s exhortations to the Israelites to perceive God in their land and lives.

References

Ruskin, John. 1843–60. Modern Painters, 34 vols (New York: J. Wiley and Sons).

———. 1857. The Elements of Drawing in Three Letters to Beginners (London: Smith, Elder & Co)

———. 1872. The Eagle’s Nest: ten lectures on the relation of natural science to art, given before the University of Oxford in Lent term, The Works of John Ruskin, vol.4 (London: Smith, Elder & Co)

———. 1874. Frondes Agrestes: Readings in Modern Painters (London: George Allen)

Hans Wertinger :

Summer, c.1525 , Oil on panel

Olafur Eliasson :

Ice Watch, 2014 , 12 blocks of glacial ice, Installation view: Place du Panthéon, Paris, 2015

John Ruskin :

Fragment of the Alps, c.1854–56 , Water colour and gouache over pencil on paper

A Feast of the Senses

Comparative commentary by Elena Greer

The catastrophe of exile to Assyria met Hosea’s fellow Israelites when the northern kingdom fell in 722 BCE. As Hosea predicted, political alliances did not save them (14:3). Nonetheless, here in chapter 14, Hosea offers the errant Israelites the promise of divine redemption.

In poetic language, Hosea paints a picture of a renewed relationship with God. This harmonious idyll is nurtured by his freely-given love; God is the dew that will make Israel blossom like a lily (v.5); Israel’s security under God’s protection will be akin to the solid anchor of the roots of the poplar (v.6). The verses offer a multi-sensory foretaste of a renewed covenant; the distinctive fragrance of the majestic cedar of Lebanon will envelop the returned sinners and the olive’s silver leaves will shimmer as a splendid echo of God’s grace (vv.5–7).

Fertility will return to the land, once the Israelites can again cultivate their own soil, for it is from God, not from humanly-made idols, that fruitfulness comes (v.8). Return to God will yield grain, wine, and fresh young shoots (vv.6–7): satisfaction, refreshment, and hope.

Hosea’s words reveal a tantalizing prospect of beauty and fertility up ahead: paradise regained. But this promise also signals a return to normality—a return to trust in the cycle of the seasons that bring labour to fruition, to the security offered by the predictability of nature’s course, which is itself a manifestation of God’s creative power and love.

Hans Wertinger’s vision of summer—a fledgling ‘landscape painting’ in the context of the history of Western art—is not just an aesthetic vision of nature, but an exposition of humanity’s experiential relationship with the land; the livelihoods and lifestyles of each figure are uniquely bound to the cyclical time dictated by nature, not human beings. As part of a cycle celebrating the seasons, this peaceful vision has a moral quality that expresses the intimate relationship between (on the one hand) everyday human life, pleasure, and prosperity, and (on the other) the non-human natural world. The rhythm of peoples’ lives is here dictated by the rhythms of the earth.

Such an image would surely have resonated with John Ruskin, who was critical of post-industrialized society’s prioritization of individual gain over collective and collaborative agendas and initiatives, as well as a detachment from nature. In his writings he railed, like Hosea, against social injustice and firmly denied the belief that unchecked commercial enterprise could ultimately benefit humankind. In his art criticism and teaching, and in his own artistic practice, Ruskin advocated a return to nature—not just its depiction but, more importantly, its true perception. Ruskin, like Hosea, saw God in nature, advising his students to ‘go to nature in all singleness of heart, and walk with her laboriously and trustingly ... believing all things to be right and good, and rejoicing always in the truth’ (1843–60: 13.624).

The physical world for Ruskin was more than a subject for paintings; it was God’s creation. He despised images that prettified or abstracted nature into a stylized vision because these were not truthful perceptions. Rather, he argued, they placed the work of man and his ego in the way of the truth, just as the Israelites had preferred Baal worship and political alliances to a trust in the Lord.

An experiential relationship with nature is Olafur Eliasson’s primary motivation in his installation. By installing blocks of frozen arctic snow in central city locations, he creates a solid tangible encounter to occupy the space of merely abstract knowledge (information about the melting of icecaps, for example, acquired only from news reports). By offering these blocks to be interacted with, he offers the opportunity for people who are otherwise geographically detached from it to relate personally to the majesty of nature. Like the plea that Hosea makes to the Israelites, the arctic blocks offer a pivot, through encounter, with which to engage, to act, and to accomplish change.

Hosea stresses that Israel’s relationship with God should be based on yada, or knowledge (see, for example Hosea 2:20). The meaning of the Hebrew word yada is not intellectual or abstract knowledge; it is experiential and emotional.

Landscape art in these three phases from Wertinger to Ruskin to Eliasson reiterates the power of the experiential, and the socially binding force of nature. As Hosea’s poetic ‘painting’ of nature emphasizes, God is present in non-human nature not only in its beauty but also in its capacity to sustain human beings through their symbiosis with it.

Although the Israelites have turned from God, they cannot avoid his essential role in their everyday lives and for that reason God will return to them despite their apostasy. Ice Watch encourages humans removed from the frozen landscapes to feel their dependency upon nature; and, twenty-eight centuries after Hosea’s words, many of us still require agitation from poetic visionaries like him.

References

Ruskin, John. 1843–60. Modern Painters, 34 vols (New York: J. Wiley and Sons).

———. 1874. Frondes Agrestes: Readings in Modern Painters (London: George Allen)

———. 1857. The Elements of Drawing in Three Letters to Beginners (London: Smith, Elder & Co)

Commentaries by Elena Greer