Psalm 29

God’s Stormy Voice

John Constable

Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, Exhibited 1831, Oil on canvas, 153.7 x 192 cm, Tate; Purchased by Tate with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, The Manton Foundation, Art Fund (with a contribution from the Wolfson Foundation) and Tate Members in partnership with Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales, Co, T13896, ©️ Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Tempered Tempest

Commentary by Bridget Nichols

The LORD sits enthroned over the flood;

the LORD sits enthroned as king for ever.

May the LORD give strength to his people!

May the LORD bless his people with peace! (Psalm 29:10–11)

This enormous work on canvas was painted in the aftermath of the death of John Constable’s wife, Maria Bicknell. Salisbury had become a place of friendship for the artist, through his association with John Fisher, one of the cathedral’s resident clergy. But for a loyal Tory and member of the Church of England like Constable, it was a time of political anxiety. The year 1829 had brought Catholic Emancipation and the Reform Bill would be enacted in 1832. It was Fisher who suggested The Church Under a Cloud as a subject.

When the painting went on to three regional exhibitions following the first showing at the Royal Academy in 1831, the rainbow had been added, with the subtitle Summer Afternoon—A Retiring Tempest. The heavy storm clouds have receded behind the cathedral. In the foreground, a carter and his horses begin to cross the stream, a boatman unties his boat, and another tiny figure is visible on the bank behind the cart. A sheepdog in the foreground among tree stumps looks alertly towards the cathedral. The leaning trunks of the trees to the left of the cathedral have learned to live in all weather. At the upper right, the sky is clearing and light falls on the meadow. The cathedral’s enormous spire pierces the storm clouds to reveal more blue sky, while a rainbow arcs leftward from the Cathedral Close over the building itself.

Ordinary, peaceful activity suggests another kind of resolution, underpinned by motifs bearing strongly biblical associations. The crossing of water from untidy growth towards the Cathedral Close recalls the salvific crossings of the Red Sea (Exodus 14:21–22) and the Jordan (Joshua 3–4). The rainbow evokes God’s covenant with Noah after the Flood (Genesis 9:12–17).

Emblematic of the Established Church, the cathedral stands secure as the agent of light. In a certain sense, God is enthroned over the flood (Psalm 29:10) and God’s people are blessed in their Church and their surroundings.

References

Evans, Mark with Stephen Galloway and Susan Owens. 2014. John Constable: The Making of a Master (London: V&A Publishing)

Vaughan, William. 2015. John Constable (London: Tate Publishing)

Katsushika Hokusai

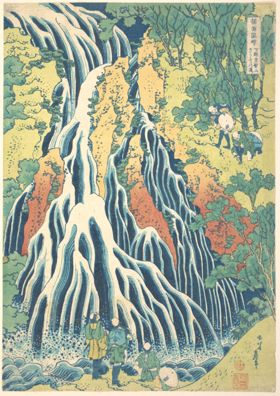

Kirifuri Waterfall at Kurokami Mountain in Shimotsuke (Shimotsuke Kurokamiyama Kirifuri no taki), c.1832, Woodblock print; ink and colour on paper, 371 x 262 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Henry L. Phillips Collection, Bequest of Henry L. Phillips, 1939, JP2924, www.metmuseum.org

Thunderous Waters

Commentary by Bridget Nichols

Ascribe to the LORD the glory of his name;

worship the LORD in holy array.

The voice of the LORD is upon the waters;

the God of glory thunders,

the LORD, upon many waters. (Psalm 29: 2–3)

From 1831–32, painter and printmaker Katsushika Hokusai produced studies of eight waterfalls in the Japanese provinces. Like his earlier fifteen studies of Mount Fuji, these were also intended to be collected as a set. Matthi Forrer points out the ‘combination of light and strong, intense blues (Prussian Blue had recently become available), mostly contrasted with whites’ in Hokusai’s treatments of the falls themselves, with their surroundings depicted in naturalistic earth colours (Forrer 2008: 16).

Where the Fuji prints emphasized the distinctive shape of the mountain, the dominant feature in these prints is falling water. In this print of Kirifuri Waterfall, on the route to the Tokugawa mausoleum at Nikkō, north of Tokyo, Hokusai brings together the drama of the vertical drop with an extraordinary characterization of the waterfall itself—a knotty primeval ‘root system’ of thick, ropey, branching streams, descending into a pool that seems almost to boil at the impact of the water.

Human figures provide a sense of scale here. Hokusai’s figures are, like us, observers: respectful and awestruck. Three stand at the foot of the falls, gazing up; two stand further up the slope watching the downward rush of the water. The heads of the lower figures are raised in an attitude suggestive of wonder, admiration, and even worship. Two stand alertly upright, while the third adopts a lower, yet still attentive posture.

For the external viewer, the scene does not depict any actual destructive event. Yet it invites us to imagine the water’s power to destroy simply by being itself, as it cleaves its way through rocks and vegetation. The artist has styled the water as a prehistoric creature, whose vast talons confront us in the foreground.

What a visual representation cannot reproduce, though, is sound. The roar of the water rushing down the mountainside into the pool is a task for the imagination, and the inner ear might hear in it the voice which the psalmist places both ‘over the waters’, and yet somehow speaking through them (Psalm 29: 3–4).

References

Forrer, Matthi. 2008. Hokusai: Mountains and Water, Flowers and Birds (Munich, London & New York: Prestel)

Jean-François Millet

The Gust of Wind, 1871–73, Oil on canvas, 90.5 x 117.5 cm, Amgueddfa Cymru –National Museum Wales; Bequest, 12/12/1963, NMW A 2475, HIP / Art Resource, NY

Whirling Oak

Commentary by Bridget Nichols

The voice of the Lord causes the oaks to whirl,

and strips the forest bare;

and in his temple all say, ‘Glory’ (Psalm 29:9)

This scene, painted late in Jean François Millet’s career, depicts a storm on the peninsula of La Hague in Normandy, close to the artist’s hometown of Gruchy. Atlantic storms frequently buffeted the area, whose ‘wind-swept fields and hills bare to the point of savageness’ are described by one of Millet’s biographers (Turner 1910: 36).

A great oak tree is caught in the moment of its fall, as a powerful gust of wind tears it out of the soil by the roots. Leaves and broken branches fly through the air. To the right, a shepherd and his sheep are fleeing, the shepherd’s outstretched arms perhaps instinctively protecting his head and face. In the foreground, the turbulence of a stream reflects the accelerating force of the wind. Only the rocks and a few houses on the horizon remain stoically motionless.

Light and dark vie for dominance. A heavy storm cloud advances, driven by the wind that is uprooting the tree. Yet there are suggestions of light behind the cloud and the horizon behind the houses is illuminated by the intense brightness that sometimes accompanies a storm.

The psalmist who sees the ‘glory and strength’ of the Lord (Psalm 29:1) present within the universe, and animating it, does not equate such qualities with order, symmetry, and beauty. In fact, Psalm 29 might be said to exult in the power of the of the thunderous and fiery voice of God, destructive not because it is malign, but because it is infinitely stronger than the elements of the world in which it plays. In that light, majesty is present in A Gust of Wind as the sheer physical force which is capable of gouging an ancient tree out of the earth where it has stood for generations.

Yet the evident fear of the shepherd and his sheep tell a different story. Indeed, although Millet is hailed as a precursor to the Impressionists, the work dramatizes the ‘classic Romantic struggle of man against the forces of nature’ (Fairclough & Dawes 2009: 104). The composition deliberately diminishes the human and animal presence in this landscape—and, even before the storm, there might not have been much that was idyllic or pastoral about it. We may wonder whether this is a glory compatible with human flourishing.

References

Fairclough, Oliver and , Bryony Dawkes. 2009.Turner to Cezanne: Masterpiece from the Davies Collection National Museum Wales (New York: American Federation of Arts)

Turner, Percy M. 1910. Millet (London: T.C. & E.C. Jack)

John Constable :

Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, Exhibited 1831 , Oil on canvas

Katsushika Hokusai :

Kirifuri Waterfall at Kurokami Mountain in Shimotsuke (Shimotsuke Kurokamiyama Kirifuri no taki), c.1832 , Woodblock print; ink and colour on paper

Jean-François Millet :

The Gust of Wind, 1871–73 , Oil on canvas

Going to Extremes

Comparative commentary by Bridget Nichols

Psalm 29 is described as a theophany. A court of ‘heavenly beings’ (v.1) provides a chorus of worship at the psalm’s opening. The introduction of the human beings dependent on God must await the final verse. In between, we encounter a manifestation of the divine in violent action in the natural world.

Its form resembles Ugaritic hymns to the god Ba’al, found in texts from the fourteenth to the twelfth centuries BCE. Some biblical scholars suggest, however, that these superficial similarities are actually techniques for asserting the supremacy of the God of Israel—adopting the conventions for praising false gods precisely in order to subvert them (Brueggeman & Bellinger 2014: 147–48).

The contrast between the magnitude and drama of the forces of nature and the comparative insignificance of human beings finds telling visual counterparts in this exhibition. A tiny shepherd and his sheep flee a storm in Jean François Millet’s A Gust of Wind. The vastness of the sky and cathedral illuminated by a rainbow loom over a very small carter and boatman (and an even smaller marginal figure) in John Constable’s Salisbury Cathedral. Visitors or pilgrims on their way to a Shinto shrine in Katsushika Hokusai’s depiction of Kirifuri Waterfall are almost comically small in relation to the waterfall itself. These figures live precariously alongside the might of storms, wind, and water. They have been captured in time, in flight from falling-tree debris, gazing in awe at the waterfall, or resuming the daily round after the weather has cleared. All three scenes remind us that we are all vulnerable to sudden extreme expressions of nature’s power.

This message of precarious contingency is a reminder that the balance of nature is infinitely delicate. Climate change is a phenomenon that brings more and fiercer storms, more destructive winds, more floods. How do we read this psalm against a backdrop of accelerating and in some places already devastating climatic effects and their associated natural disasters with long-term consequences for human beings and other species?

The psalmist captures a tension between our fear of these forces and our fascination with their majestic beauty—and the fearsomeness and fascination of the God behind them. There is something exhilarating about the psalm’s almost playful portrayals of a divine voice capable of altering and destroying the landscape. At the same time, we cannot forget that our own relationship with nature is no game. It is areas of the world which have not contributed to climate change that now endure its most savage and enduring effects. Climate conferences have pointed the finger of blame for this at rich economies which have treated the planet’s resources as playthings.

Nevertheless, the psalm’s final verse confidently seeks blessing.

Of the three works, it is Constable’s almost improbable canvas that allows most room for an exploration of blessing alongside the themes of fear and fascination. Although the storm clouds have not fully cleared, the spire of a monumental and enduring place of worship pierces them to reveal a small area of blue sky. The rainbow, while a natural phenomenon, seems to invite associations with the covenant with Noah, made after the Flood. Playfully, the sheepdog brings to mind the hidden presence of Christ the Good Shepherd. In this landscape of watery meadows, flooding is always a danger; the threat of drowning is always there. The viewer senses that the carter has waited for a relatively safe time to cross the stream after the rain has ceased, but the horses’ legs are still half-immersed in water. The painting offers more than an easy proposition of ‘natural order’ restored after the chaos and violence of the storm. In fact, the opposite seems true. Order is always temporary. Human life tentatively goes on, but it is perennially fragile in relation to the enormous forces and energies of the natural world. Hope may persist, but often in spite of the physical evidence.

Yet it does persist, as it does in this psalm’s petitions. The ‘strength’ of the Lord is also looked for in the strengthening of ‘people’ and of ‘peace’ (v.11).

The artist Lucien Freud described an argument with Neil MacGregor about Constable’s painting, while the latter was Director of the National Gallery:

[MacGregor] said it’s so overdone, over-egged, over the top: it’s got everything at once, including a rainbow. But, I said, I want him to put everything in there. More water, more skies. In the end you have to really love Constable to like that. It’s sometimes exciting to put in everything you like. (Freud 2003: 44)

Constable’s work both acknowledges the dangerous tumultuousness of the world, and celebrates it as a place that merits our exuberant love. Despite its placid foreground, it is an exuberant response to an exuberant creation. Hope demands (and depends on) nothing less.

References

Brueggemann, Walter and William H. Bellinger, Jr. 2014. Psalms (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Freud, Lucien with William Feaver. 2003. On John Constable (London: The British Council)

Handy, Lowell K. Handy (ed.). 2009. Psalm 29 through Time and Tradition (Cambridge: James Clarke)

Commentaries by Bridget Nichols