Psalm 37

The Inheritance of the Blameless

Sergio Gomez

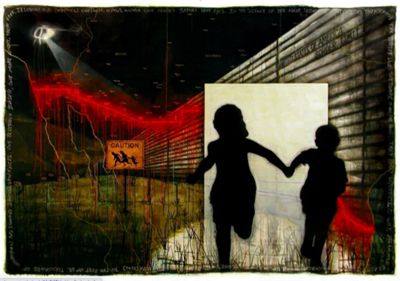

The Bleeding Border, 2008, Acrylic on Paper/Canvas, 195.58 x 284.48 cm, Collection of the artist; ©️ Sergio Gomez, Courtesy of the artist

Broken Beauty

Commentary by Cecilia González-Andrieu

What does it mean to trust in God? Does it mean to stay put and perish, or does it mean to run, seek refuge, and believe God will accompany and see us through a harrowing journey? Displaced persons around the globe must answer this every day. For most, just as for the children in The Bleeding Border, there may be no choice but to trust that ‘the righteous [who] are generous and keep giving’ (Psalm 37:21 NRSV) may be waiting on the other side.

The monumental scale of this work gives the viewer nowhere to retreat to. The life-sized children are running and it is impossible to tell in which direction. Are we joining their dash toward the light-filled door? Will it close before we reach it? Or, instead, are the children running headlong toward us? Will we take them up in our arms and provide the refuge God promises? Will those who hold the power of life and death over these children be among God’s righteous, who even if they have little themselves (v.16) are willing to share it?

The land—so central in this psalm, and promised repeatedly to those who do good and wait for the Lord—is a co-protagonist in this work. Superimposed over the scene and most visible against the night sky, the border between the United States and Mexico is rendered as flesh, an open wound dripping blood onto towns and villages, some real and some imagined, with names like El Diablo (the devil) and El Cielo (heaven). The handwritten text framing the painting shatters any possibility of absolving ourselves from responsibility. These are ‘Someone’s children, anonymous shadows to the rest of us. Thousands of unspoken and ignored inconveniences’. Repeated in a thousand places with a thousand faces, can the God who mends the broken, mend this? How does this story end? (Luiselli 2017: 55).

References

Luiselli, Valeria. 2017. Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press)

Trina McKillen

The Children, 2015–18, 20 communion dresses, 20 altar boy vestments, Irish linen, thread, gold leaf, Collection of the artist; ©️ Trina McKillen; Photo courtesy of Trina McKillen and Lisa Sette Gallery

Wounded Beauty

Commentary by Cecilia González-Andrieu

Who are the blameless the psalmist calls righteous? (Psalm 37:18–37). Who are the defenceless who become the target of the wicked? Has God taken a vacation? (Brandt 1973: 59).

Psalm 37 states that God’s vindication of the innocent ‘will shine like the light, and the justice of [their] cause like noonday’ (v.6 NRSV). But how can we say this to those whose childhood is shattered by abuse? How can we assure them that God is on their side?

In The Children, Trina McKillen—who found refuge in her Catholic parish during ‘The Troubles’ in Belfast—exposes the agonizing betrayal of having the community we love converted into a place of suffering (McKillen 2020: 4–9). As she shines multiple lights on innocent children, victims of abuse from those they trusted, their small ghostly figures—represented by suspended First Communion dresses made from the delicate lace which is so traditional to Catholicism—hauntingly evoke the joy and festiveness of the moment when the liturgy is about to begin.

The children’s evanescent presence is searing precisely through their absence, disclosing a wounded innocence (García-Rivera 2003: xi). In the work we are confronted by their pain, and asked to wrestle with what it is to love a tradition that betrays us. Although no explicit violence is represented here, what is evil is in plain sight in The Children. The communal celebration of Christ’s presence is agonizingly interrupted by the embroidered gold serpent on each ‘child’s’ breast, ready to devour them. They bear on themselves the symbol of evil entwined with the keyhole through which both the wicked and the righteous may enter.

The Children exposes innocence at its most vulnerable; faith traditions as beautifully evocative and also excruciatingly wounded; and wickedness as ready to use whatever means it can as an opening to strike. Will our vigilance and commitment to ‘do good’ (vv.3,27) break the grip of the wicked and bring the restoration that God promises?

References

Brandt, Leslie F. and Corita Kent. 1973. Psalms/Now (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House)

García-Rivera, Alex. 2003. A Wounded Innocence: Sketches for a Theology of Art (Collegeville: Liturgical Press)

John August Swanson

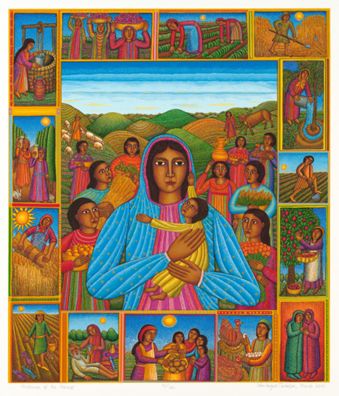

Madonna of the Harvest, 2010, Hand-printed serigraph, Collection of the artist; ©️ 2010 John August Swanson; Photo: Courtesy of John August Swanson Studio / Trust www.johnaugustswanson.com

Prophetic Beauty

Commentary by Cecilia González-Andrieu

Psalm 37 can be painfully challenging for those who are poor and needy (v.14). Although the psalmist argues to the contrary (v.25), they know they have experienced their ‘children begging for bread’. Does the lack of bread point to God’s displeasure and abandonment, or is it evidence instead of the selfishness and unjust hoarding of wealth by those the psalmist calls ‘wicked’ (named sixteen times in this psalm)?

How do we reconcile a ‘God who loves justice’ and does ‘not forsake [God’s] faithful ones’ (v.28 NRSV) with the pervasive economic exploitation, and the violence against the most vulnerable, that this psalm denounces?

How can God’s view of our world—in its confidence that the powerful will fade like the grass and that those who are most lowly will ‘inherit the land’—be so very different from what we see with our own eyes?

How can we believe this? Better yet, how can we help bring this about?

The Madonna of the Harvest suggests answers to these questions by bringing God’s view into focus for us in dazzling beauty. The promised inheritance of the land, rhythmically repeated in the psalm, makes clear that God’s vision is not about a world to come, but abundantly incarnated in this beautiful world of ours, in its earth and its complicated reality. This brown-skinned Madonna, lacking a halo or any suggestion of special status, looks at us with eyes that plead the case of vulnerable women and children. A reimagined Virgen de Guadalupe, she holds her child, every child, while standing in the fields where she is just one more of the workers who needs us to see her and advocate for her. As her plaintive gaze breaks our hearts, those who are poor and often rendered invisible by society surround her, and are here instead lifted into the sacred as holy icons by John August Swanson, himself the child of impoverished immigrants (González-Andrieu 2021a and 2021b).

References

González-Andrieu, C. 2021a. ‘Remembering John August Swanson: A Life Dedicated to Art, Faith, and Justice, 23 September 2021’, www.americamagazine.org [accessed 15 March 2022]

_______. 2021b. ‘John August Swanson lived his faith, worked for a better world through art, 24 September 2021’, www.ncronline.org [accessed 15 March 2022]

Sergio Gomez :

The Bleeding Border, 2008 , Acrylic on Paper/Canvas

Trina McKillen :

The Children, 2015–18 , 20 communion dresses, 20 altar boy vestments, Irish linen, thread, gold leaf

John August Swanson :

Madonna of the Harvest, 2010 , Hand-printed serigraph

When Broken Hearts Say ‘Enough!’

Comparative commentary by Cecilia González-Andrieu

The Psalter speaks eloquently with multiple voices. Some of its songs express the deepest despair; others tend toward the light; and still others expose unresolved tensions. As they struggle, like Jacob during his long night of wrestling with God (Genesis 32:22–31), it is the act of wrestling that predominates and the possibility that at the end of it all there may be no definitive answer and we will be left limping, yet renewed in our resolve to walk with God.

Psalm 37 is one of these tension-filled psalms of wrestling with what is difficult, sometimes called Wisdom Psalms. It is not quoted often, yet one of its central ideas, that the poor and the meek, the broken and the scorned, the oppressed and discarded of the world will ‘inherit the land’, is a major influence on the Beatitudes of the New Testament (Matthew 5:3–12; Luke 6:20–26). The Beatitudes in turn have become an eloquent roadmap for movements that denounce oppression and ‘incarnate the duty of hearing the cry of the poor’ (Evangelii Gaudium 2013).

The three works in this exhibition share this focused attention on the vulnerable of the world. Brimming with the conviction that God acts in history, these works present us with something almost impossible to do with anything but art: they bring beauty to bear on suffering and—through that contrast—jolt us out of our inaction and complacency.

Madonna of the Harvest, The Children, and The Bleeding Border, present us with a paradox: the improbable presence of abundant faith in situations where faith could be (should be?) destroyed. Psalm 37 hopes for this persistent faith as it invites its hearers to face what seems to make no sense by clinging to their trust in God. We can hear the community’s questions which the psalmist is trying to answer: Why do the wicked flourish? Why do violence and exploitation against the vulnerable go unchecked? When will God rescue us? The psalm asks for ‘patience and trust’, but it also offers testimony that such trust will be answered not in some other life but in this one. Both the psalm and these artworks build up those they encounter to become agents of transformation.

The three artworks have the world’s innocent victims as their central characters and pull us into their reality so we may newly see them. Once we have entered, they involve us in activating the kind of action the psalm envisions when it speaks of generosity, making peace, rescuing, and a future. In the Madonna of the Harvest, the poverty and marginality of those who work the land is banished in the jewel tones of abundance, community, and sharing. In The Children, the shame of abuse is pierced through by the light of memory and the heartbreak of beauty and lives destroyed. And in the Bleeding Border, the land which has been mercilessly cut and bleeds its crimson red finds the possibility of healing in the brilliant light of an open door.

The hearer of the psalm and viewer of the art is the ultimate subject here. God’s promise of salvation awaits their active cooperation. Not magical, not in an otherworldly future, the work of the righteous has a particular shape; it intervenes in particular moments; it makes God present in a specific reality. When our hearts are broken, when God’s heart is broken, these works call on us to cry out ‘enough!’.

Taking the side of the blameless as God does, we can, we must, do something so that the ones who have been trampled will triumph, and in the here and now—in our world—truly inherit the land. Beauty overcomes suffering precisely in the actions for others of the just.

References

Pope Francis. 2013. Evangelii Gaudium (Rome: The Vatican), no. 193

Commentaries by Cecilia González-Andrieu