Genesis 16

Hagar’s Exile and Return

Frederick Walker

The Lost Path, 1863, Oil on canvas, 9.1 x 13.3 cm, The Makins Collection, USA; Bridgeman Images

Fallen/Falling

Commentary by Zanne Domoney-Lyttle

A woman clutching a baby is lost in the wilderness. Head bowed against the wind, she drags herself along a snow-laden path, protecting herself and her baby against the cold. The canvas is almost entirely white, representing heavy snowfall and enhancing the sense of disorientation. There is an absence of familiar reference points, either for the viewer or the subject of the painting—all seems lost.

Frederick Walker’s painting is about a lost woman, but some scholars argue that she also signifies a prevalent type in Victorian art: that of the ‘fallen woman’ (Nead 2015: 1). If so, then the woman in this painting has lost not just her way, but—when judged by the conservative attitudes of the Victorian era—her moral compass (Howell 2015).

The ‘fallen women’ of Walker’s era were often excluded from society along with their children who were viewed as illegitimate. Walker’s painting was meant to be a social commentary urging viewers not to judge such women but to take pity on them and offer them aid (Mills 2015: 3). Like the story of Hagar who is banished into the wilds of the desert, first with her unborn child (Genesis 16:6–14) and then again once she gives birth to her son Ishmael (Genesis 21:9–21), The Lost Path communicates the themes of desperation, plight, and the desire to survive as well as to protect our loved ones.

Hagar’s story has parallels with the unwed mothers of Walker’s era, since she too faced banishment from the community which enslaved her. We can see this in Genesis 16:4–7 when Sarai judges Hagar as being conceited above her station, ‘treats her harshly’ (Genesis 16:6), and expels her into the wilderness with no help—not even the skin of water and the food that Abram would give her and Ishmael in Genesis 21:14 (Sarna 1994: 120).

Similarly, it is likely that Hagar would have faced oppressive treatment at the hands of others if she had survived her wandering in the desert, since she was a pregnant foreign slave with no connections or status. Like Walker’s woman who has lost her way in the snow, Hagar is a victim of judgement and oppression linked to her identity as an unwed mother, as well as being perceived as a threat to the social hierarchy of her community (Trible 1984: 15).

References

Howell. Caro. 2015. ‘Director Caro Howell on the Foundling Hospital Petitions’, www.foundlingmuseum.org.uk/director-car-howell-on-the-foundling-hospita… [accessed 16 December 2020]

Mills, Victoria. 2015. ‘The Fallen Woman and the Foundling Hospital’, The Fallen Woman Exhibition Guide (Foundling Museum)

Nead, Lynda. 2015. ‘The Fallen Woman’, The Fallen Woman Exhibition Guide (Foundling Museum)

Sarna, Nahum. 1994. The JPS Torah Commentary: Genesis (Philadelphia: JPS)

Trible, Phyllis. 1984. Texts of Terror: Literary Feminist Readings of Biblical Narratives (Philadelphia: Fortress Press)

Jean-François Millet

Hagar and Ishmael, 1848–49, Oil on canvas, 147 x 236.5 cm, The Mesdag Collection, The Hague; hwm0262, Courtesy of The Mesdag Collection, The Hague

Hope?/Hoping

Commentary by Zanne Domoney-Lyttle

At first glance, Jean-François Millet’s unfinished painting of Hagar and Ishmael is bleak, hopeless, and distressing to look at. Depicting the events of Genesis 21:15–16, the painting is an uninviting mixture of browns, beiges, and yellows, and the figures of mother and child almost meld into the undulating landscape.

What has this to do with Genesis 16? Millet’s painting imagines the second time Hagar has been cast out of Abram’s family, but on closer consideration it visually links the viewer back to the first story of Hagar and Ishmael’s exile and rescue in Genesis 16:6–12. In that story, Hagar and her unborn son are saved by an angel of the Lord and by a spring of water (Genesis 16:7) and are given a divine promise that Ishmael will go on to survive and, potentially, thrive. Reading the work in relation to this promise casts Millet’s painting into a new light: though the situation seems bleak, though Hagar has physically removed herself from her dying child, there is hope. High above the pair, the barren landscape softens into blue skies, and there is hint of foliage in the distance. Life has survived this harsh desert, and so will Hagar and Ishmael.

Millet frequently featured scenes of peasants, labourers, and the socio-economically disadvantaged in his works. While his paintings do not fully capture the hardships of the lives of the poor, Millet reminds us through his ‘mysterious, almost celestial figures’ (Waller 2008: 190)—of peasant women in particular—that there is beauty and hope in all circumstances.

Millet’s work was commissioned by the French government and remains unfinished—probably because he left to live elsewhere. Yet although it is technically unfinished, it successfully depicts the emotive components of Hagar’s story and in that way may be considered complete. With the pared down palette of colours and the bare elements of the story exposed to the viewer, we may find ourselves placing ourselves in Hagar’s position as she raises her eyes to the sky, seeking aid for her dying son. By reading the text of Genesis 16:5–7 into this painting, it is suggested that all hope is not lost.

References

Waller. Susan. 2008. ‘Rustic Poseurs: Peasant Models in the Practice of Jean-Francois Millet and Jules Breton’, Art History, 31.2: 187–210

Thomas Rowlandson

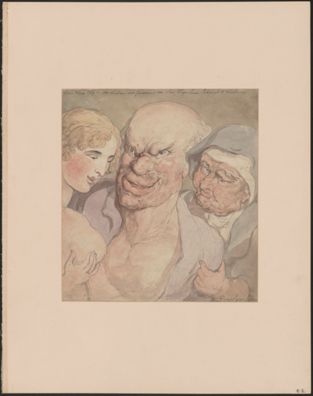

Genesis 16 verse, chapter 14: And Abraham was fourscore and six when Hagar bore Ishmael to Abraham, 1782–1800, Watercolour on paper, 230 x 210 mm, Boston Public Library; 18_03_000001, Boston Public Library, Thomas Rowlandson Collection, Prints and Drawings

Seen/Seeing

Commentary by Zanne Domoney-Lyttle

The figure of Abram occupies most of the space in this watercolour illustration, executed in the style of caricature. With unbuttoned shirt, he leers out from the centre of the image. On the right, Sarai as an old woman hangs on his shoulder in a way that seems to symbolize her dependency or perhaps her grip on him; on the left, Hagar presses her naked breast against Abram’s exposed chest.

Abram is both the separator and the connecting factor between these two women. It is a visualization that upholds Athalya Brenner-Idan’s suggestion that biblical women are often cast in pairs, as opposites of each other, so that when combined they become one ‘whole’ woman (Brenner-Idan 2017: 92; Trible 1984: 10). The contrast here between Sarai and Hagar could be read as representing two disjointed aspects of womanhood, with Abram’s disturbing presence between them as their only middle ground.

The inscription at the top of the image reads: ‘Genesis 16 Verse Chap 14. And Abraham was fourscore & six when Hagar bare Ishmael to Abraham’. The citation is incorrect: in fact, Rowlandson’s inscription quotes Genesis 16:16. The image, meanwhile, seems to represent events earlier in the chapter, when Hagar has conceived and looks with contempt upon her mistress (Genesis 16:4). A slight hint of a pregnant stomach may suggest itself underneath Hagar’s breasts, and Hagar’s expression is pleased, while Sarai looks concerned.

In the interval between verse 4 and verse 16 (and thus between what is recorded in Rowlandson’s inscription and what is shown in his image), Hagar is banished to the wilderness by Sarai. She there receives a revelation that she will give birth to Abram’s son despite the tensions that await her on her return to Abram and Sarai’s home. It is a moment where the future is both revealed to and celebrated by Hagar as one in which she will triumph over Sarai’s mistreatment of her (Alter 1996: 71).

Furthermore, there is a textual connection between Genesis 16:4 and Hagar’s wilderness experience. Both are about the theme of seeing. Hagar sees that Sarai has diminished in status because Hagar (not Sarai) carries Abram’s child. And Hagar also sees God at the place in verse 14 she calls Beer-lahai-roi (‘the well of one who sees and lives’).

Rowlandson too invites a new seeing—presenting this story afresh, as Hagar steals the limelight from the grotesque figures of Abram and Sarai.

References

Alter, Robert. 1997. Genesis: Translation and Commentary (London: W. W. Norton)

Brenner-Idan, Athalya. 2017. The Israelite Woman: Social Role and Literary Type in Biblical Narrative (London: T&T Clark)

Trible, Phyllis. 1984. Texts of Terror: Literary Feminist Readings of Biblical Narratives (Philadelphia: Fortress Press)

Frederick Walker :

The Lost Path, 1863 , Oil on canvas

Jean-François Millet :

Hagar and Ishmael, 1848–49 , Oil on canvas

Thomas Rowlandson :

Genesis 16 verse, chapter 14: And Abraham was fourscore and six when Hagar bore Ishmael to Abraham, 1782–1800 , Watercolour on paper

Reflecting Reality or Distorting the Story?

Comparative commentary by Zanne Domoney-Lyttle

Although this story falls in the middle of the Abram narrative (Genesis 12–25), and is linked both to his future (in the form of descendants) and to his covenant with God (in terms of God's keeping of God's promise to make Abram a ‘great nation’; Genesis 12:2), Abram is not a central figure in Genesis 16. Instead, this is a story about and between two women, both of whom have a controlling stake in the future direction of Abram’s fate, whether in an active or a passive manner.

How we understand the function and role of those women is essential when it comes to viewing artworks which recall their stories. For example, if we choose to accept Athalya Brenner-Idan’s suggestion that Hagar and Sarai are intended to represent two incomplete women who become one whole person when combined (Brenner-Idan 2017: 92), then Thomas Rowlandson’s image becomes more than a lewd reference to a three-way relationship between Hagar, Abram, and Sarai. Instead, we might see Hagar as the polar opposite of Sarai and recognize that Abram is the connection between the two. As such, the two women rely on his presence so that their own stories can be understood and contextualized. Abram is the pivot around which their stories turn.

If we refute Brenner-Idan’s claim, however, we can be helped to liberate the women from their reliance on Abram as a connecting factor and as such, perhaps better understand and empathize with their experiences. Artists can help us with this process through various artistic choices which may emphasize or obscure particular details.

In Jean-François Millet’s painting, for example, the imagery of the hot and barren landscape is both a reflection of, and a contrast with, Hagar and Ishmael’s immediate situation. It is a reflection insofar as Hagar is herself in despair. Her son appears lifeless, much like the desert around them. It is a contrast because—though Hagar is in distress and Ishmael appears at least near death—the survival of both still remains a possibility, just as there is life in the small piece of shrub which grows in the background of the image. So even the contrast opens an insight into elements of Hagar’s destiny that are yet to be revealed.

In Frederick Walker’s painting of a ‘fallen’ woman, we are encouraged to view the situation of Hagar and other ‘non-conforming’ mothers from such women’s perspectives. We are given the opportunity to see that they may be part of a harsh and inhospitable environment; that their struggle for survival can become an epic quest; but that their futures will nevertheless always be uncertain. Walker’s painting triumphs here because it also communicates the sense of isolation and loneliness which often accompanies such journeys.

The scholarly idea of pairs of women ‘mirroring’ each other to make a ‘complete’ women may be less a key to the interpretation of artworks like Rowlandson’s (and others), and more, perhaps, a reflection of how viewers’ assumptions can sometimes operate in relation to such works. More specifically, it can reveal patriarchal assumptions that women are incomplete if they do not possess a variety of character traits. Such androcentric assumptions often underpin the way women perceive themselves and other women around them.

In the case of the works in this exhibition, it may be less the works’ artists than their viewers (whether male or female) who seek to avoid facing the reality of Hagar’s situation. Viewers may be tempted to focus only on the heroic elements of her story (as we find them in Walker’s or Millet’s works) or on the titillating aspects of her narrative (as we are confronted with them in Rowlandson’s watercolour). But distorting the reality of Hagar’s—and Ishmael’s—story by such a selective focus cushions the blow of the harsh reality behind it.

Reflection upon Hagar’s situation in Genesis 16—where her enslavement leads to enforced pregnancy and ultimately to banishment—can play an important part in deepening our interpretation of, and enlarging our response to, these artworks. Conversely, when viewed attentively, Rowlandson’s, Walker’s, and Millet’s works may help to awaken our discomfort as we read the biblical text. Even if only small glimpses, they open a little more of Hagar’s reality to us than we may initially want to see. If these works begin to take us in such directions, it is a journey we should continue.

References

Brenner-Idan. Athalya. 2017. The Israelite Woman: Social Role and Literary Type in Biblical Narrative (London: T&T Clark: London)

Commentaries by Zanne Domoney-Lyttle