Matthew 21:1–11; Mark 11:1–10; Luke 19:29–40; John 12:12–19

Christ’s Triumphal Entry

T'oros Ṙoslin

Entry into Jerusalem, from T'oros Roslin Gospels, 1262, Manuscript illumination, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore; March 1935, given to The Walters Art Gallery by Mrs. Henry Walters, W.539, fol. 174r, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Image and Prophecy

Commentary by Jacopo Gnisci

Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion!

This miniature of the Entry into Jerusalem comes from a Gospel book painted and copied in 1262 at Hromkla, seat of the Armenian Catholicos from 1151 to 1292 CE. It was produced by the workshop of T'oros Roslin, one of the most accomplished Armenian illuminators of the thirteenth century. Instead of grouping images from the life of Christ at the beginning of the manuscript, as was customary in earlier Armenian manuscripts, T'oros Roslin, like other Cilician artists, distributes the miniatures across the manuscript, placing them close to the relevant Gospel passages. The scene shown here was aptly placed next to the section of the Gospel of Mark that describes the Entry into Jerusalem (11:1–10).

This solution, which allows for a closer connection between text and image, shows that Armenian artists used miniatures for interpretative purposes. T'oros Roslin’s awareness of the potential of religious art as an exegetical tool led him to include a bearded figure with a scroll, to the right on top of the city of Jerusalem. The inscription on the scroll—‘Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion!’—is the first part of a verse from Zechariah (9:9), the second part of which is quoted in Matthew (21:5) and John (12:15). It prophesies that the king of Jerusalem will approach the city mounted on a ‘colt’. Since the prophecy is not quoted in Mark, it is likely that T'oros Roslin added this detail to remind the reader of the Christian claim (supported by Matthew and John) that the Entry into Jerusalem was a messianic act in fulfilment of Zechariah (9:9).

Just like the Evangelists, then, T'oros Roslin uses the Old Testament Scripture to interpret the New.

References

Der Nersessian, Sirarpie. 1973. Armenian Manuscripts in the Walters Art Gallery (Baltimore: Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery), pp. 10–30

Unknown Ethiopian artist

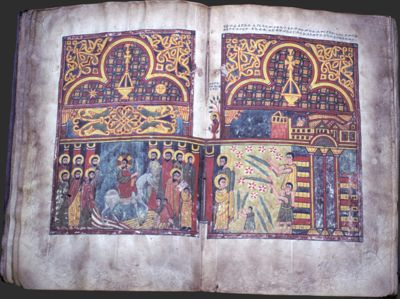

Entry to Jerusalem, from the Kebran Gospels, c.1375–1400, Manuscript illumination, Kebran Gabriel Church, Lake Tana, Ethiopia; MS Tanasee 1, Photo: © Michael Gervers, 2006

Image and Liturgy

Commentary by Jacopo Gnisci

Hosanna to the Son of David!

Miniatures of the Entry into Jerusalem are attested in many medieval Ethiopic Gospel books where the episode often takes up a two-page spread to stress the triumphal character of the occasion.

In the Kebran Gospels, Jesus is surrounded by his disciples and rides towards a crowd that welcomes him by spreading garments on the road and waving palm branches (Matthew 21:8; Mark 11:8; Luke 19:36; John 12:13). Jesus is met by a group of children even though the canonical narratives do not mention them at this point in the story. Their presence foreshadows the account of the Cleansing of the Temple in Matthew (21:12–17) during which Jesus is praised by the children who cry out ‘Hosanna’. Their acclamations anger the high priests and scribes, but Jesus explains and justifies their actions by reciting the first half of Psalm 8:2, ‘Out of the mouth of babes and sucklings thou hast brought perfect praise’, to prove that by accepting him as the Messiah the children are fulfilling this prophecy.

Looking more closely at the Kebran miniature, we can see a small figure perched upon the tree above the welcoming crowd and identified by a caption as Zacchaeus—a tax collector who climbed up a sycamore tree to see Jesus in Jericho. His story is peculiar to Luke’s Gospel (19:1–10) who uses it to show that through Jesus salvation becomes possible even for sinners such as Zacchaeus and to introduce the parable of the Ten Pounds/minas (19:11–27; a parallel of the parable of the Talents in Matthew 25:14–30).

In Ethiopia this pericope is read on Palm Sunday so the decision to include Zacchaeus was probably inspired by the liturgical practices of the Ethiopian church. However, the presence of Zacchaeus, in view of the connection with the parable of the Ten Pounds, also gives an eschatological dimension to the whole scene. In Matthew 25, this story is part of a group of parables about the kingdom of heaven. The eschatological connotations of this image are also brought into play by the sun and moon on the left page which evoke the prophecy of the destruction of the Temple (Matthew 24:29).

References

Gnisci, Jacopo. 2015. ‘The Liturgical Character of Ethiopian Gospel Illumination of the Early Solomonic Period: A Brief Note on the Iconography of the Washing of the Feet,’ in Aethiopia fortitudo ejus: Studi in onore di Monsignor Osvaldo Raineri in occasione del suo 80° compleanno, ed. by Rafał Zarzeczny (Rome: Pontificio Istituto Orientale), pp. 253–75

Unknown artist, Egypt

The Entry into Jerusalem, c.1300, Cedar wood, 31 x 13.1 cm, The British Museum, London; 1878,1203.3, The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Image and Christology

Commentary by Jacopo Gnisci

They put him to death by hanging him on a tree.

While images of the Entry into Jerusalem celebrate the manifestation of Christ’s divine glory, most Christians will know that the story also marks the beginning of the Passion narrative. Jesus descends from the Mount of Olives, from where he will ascend to heaven (Acts 1:9–12), knowing that in proceeding towards Jerusalem he also moves towards his crucifixion on Golgotha (Matthew 27:33; Mark 15:22; John 19:17). In the carved scene shown here, which is part of a set of ten relief panels that decorated the double doors of the sanctuary screen from the Hanging Church in Cairo, the artist has skilfully combined these two moments of triumph and death into a single image.

Instead of riding towards Jerusalem, as he does in the other two works in this exhibition, Christ is shown sitting side-saddle on a colt on top of a tree which alludes to the cross of the crucifixion and the tree of life in Genesis (2:9) and Revelation (2:7; 22:2). This reading is based on Peter (Acts 5:30) and Paul (Galatians 3:13) who refer to the cross as a ‘tree’. The reference to the crucifixion is reinforced by the small cross on Christ’s nimbus.

Notwithstanding the allusion to the crucifixion, the scene on the panel emphasizes Jesus’s triumph over death rather than his human suffering. This impression is strengthened by the fact that the donkey has an unnaturally curved back, probably thus creating a visual parallel with depictions of the Maiestas Domini where Jesus sits on a globe. By presenting Jesus as an enthroned ruler suspended above a crowd of onlookers, the panel ultimately presents the Entry into Jerusalem as a prefiguration of the Second Coming (Matthew 24:30; 1 Thessalonians 4:17).

References

Hunt, Lucy-Anne. 1989. ‘The Al-Mu Allaqa Doors Reconstructed: An Early Fourteenth-Century Sanctuary Screen from Old Cairo’, Gesta, 28.1: 61–77

T'oros Ṙoslin :

Entry into Jerusalem, from T'oros Roslin Gospels, 1262 , Manuscript illumination

Unknown Ethiopian artist :

Entry to Jerusalem, from the Kebran Gospels, c.1375–1400 , Manuscript illumination

Unknown artist, Egypt :

The Entry into Jerusalem, c.1300 , Cedar wood

Visions of Jerusalem

Comparative commentary by Jacopo Gnisci

The three images featured in this exhibition, although separated by about a century, have a lot in common.

First, they all had a liturgical function and were used in churches that adhered to the Oriental Orthodox tradition, where they would have played an important part in the construction and maintenance of a communal identity.

Second, they present a narrative which escapes the conventional bonds of time and space: in the T'oros Roslin Gospels an Old Testament prophet is presented as a witness to a New Testament event; in the Kebran Gospels an episode that occurred in Jericho is situated in front of the gates of Jerusalem; and in the panel from the Hanging Church the viewer is directed towards Christ’s redeeming sacrifice upon the cross and his Second Coming. The representational approach which characterizes these three scenes is based on a concept of history that owes much to biblical exegesis and that conceptualizes the past not as a linear sequence of moments but as a series of interlinked and supernaturally guided events. For this reason, despite their similarities, the three images work like a commentary and lead the viewer to different interpretations of the same theme through subtle variations in content.

In this respect, it is interesting to focus on the distinctive ways in which Jerusalem is represented in the three images. In the T'oros Roslin Gospels the gate of the city is surmounted by two small buildings and a ciborium. This ciborium, which often appears above Jerusalem in medieval Armenian miniatures, evokes the aedicule built around the tomb of Jesus (Matthew 27:59–60; Mark 15:46; Luke 23:53; John 19:41–42) inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The motif plays on the ideological relationship between the Temple of Jerusalem and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which came to be regarded as the new Temple of Jerusalem after the fourth century. Therefore, the city towards which Jesus advances in the T'oros Roslin Gospels represents the historical Jerusalem as well as the New Jerusalem described in the visions of Ezekiel (Ezekiel 40–48) and John of Patmos (Revelation 3:12; 21:2, 10).

In the Ethiopian miniature from the Kebran Gospels, the Entry into Jerusalem is situated within an ambiguous space where inside and outside are not clearly distinguished. On the one hand, we see a series of small buildings above the arched gate to the right. On the other hand, there are lamps hanging from the upper frames of the two panels and columns behind the group in procession. The figure bent over a manuscript in front of Jesus provides a key for understanding this spatial ambivalence: the image has two dimensions, one represents the biblical story, the other its liturgical re-enactment. In the Kebran miniature Jerusalem stands not only as a symbol for the earthly and heavenly city but also as the ‘mother’ of all churches (Galatians 4:26).

Finally, in the carving from the Hanging Church in Cairo, Jerusalem is not even represented. How do we explain this omission? The answer lies in the original function of the panel which was part of a set of carvings that decorated the double doors of a sanctuary barrier of a Coptic Church. Medieval Coptic authors describe the church sanctuary as being the tabernacle, the holy of holies, and an image of the heavenly Jerusalem. It follows that the doors to the sanctuary represent the gates of the New Jerusalem and of the new Temple. Thus, the artist of the panel did not need to represent Jerusalem because the scene decorated a set of doors which symbolized its gates and that were placed in front of the sanctuary that was taken to represent heaven. The function of the panel showing the Entry into Jerusalem, combined with the eschatological references discussed elsewhere in this exhibition, adds a layer of meaning to the detail of the tree, which can now additionally be understood in the light of Revelation 22:14: ‘Blessed are those who wash their robes, that they may have the right to the tree of life and that they may enter the city by the gates [emphasis added]’.

References

Bolman, Elizabeth S. 2006. ‘Veiling Sanctity in Christian Egypt: Visual and Spatial Solutions’, in Thresholds of the Sacred: Architectural, Art Historical, Liturgical, and Theological Perspectives on Religious Screens, East and West, ed. by Sharon E. J. Gerstel (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks), pp. 73–106

Frazer, Margaret E. 1973. ‘Church Doors and the Gates of Paradise: Byzantine Bronze Doors in Italy’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 27: 145–62

Gnisci, Jacopo. 2014. ‘Picturing the Liturgy: Notes on the Iconography of the Holy Women at the Tomb in Fourteenth- and Early Fifteenth-Century Ethiopian Manuscript Illumination’, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 78.3: 557–95

Ousterhout, Robert. 1990. ‘The Temple, the Sepulchre, and the Martyrion of the Savior’, Gesta, 29.1: 44–53

Commentaries by Jacopo Gnisci