Matthew 21:33–46; Mark 12:1–12; Luke 20:9–19

The Wicked Tenants

Works of art by Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, Brothers Dalziel, John Everett Millais and Unknown artist

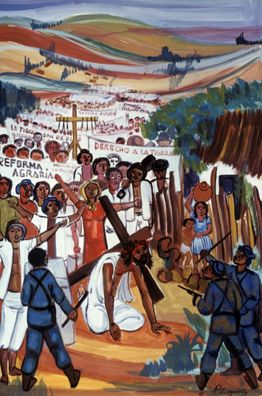

Adolfo Pérez Esquivel

7th Station of the Cross: The Land Question, 1992, Acrylic [?]; Courtesy of Alastair McIntosh and Coopération Internationale pour le Développement et la Solidarité

A Non-Violent Battle for Justice

Commentary by David B. Gowler

Adolfo Pérez Esquivel’s Stations of the Cross was created for the five-hundredth anniversary of the colonization of the Americas. It reflects on Jesus’s Passion and connects it with the experiences of contemporary Latin American people suffering from colonization, poverty, hunger, illiteracy, economic inequality, and other oppression including torture, imprisonment, and death. These contexts mirror the oppression of the Jewish people during the time in which Jesus lived, taught, and was martyred—and Jesus’s own victimization.

For example, the sufferings of campesinos (landless, tenant, and/or peasant farmers) and other oppressed people in Latin America, are reflected in Jesus’s journey to the Cross. Station 7 (‘The Land Question’), where Jesus falls for the second time under the weight of the cross, illustrates the plight of the landless poor. The landscape in the background illustrates that abundant land is available for everyone in a just society, but the rest of the painting depicts the violent oppression under which the poor suffer. The soldiers guarding Jesus wear contemporary uniforms and are equipped with a gun, clubs, and a shield. Crowds of people march behind Jesus in protest, and their signs link his torture at the hands of the elite with theirs: Reforma Agraria (agrarian reform) and Derecho a la tierra (right to land). In addition, most tellingly, the seven black ropes on the cross in the midst of the crowd represent murdered campesinos (McIntosh 2005). Similarly, Station 3’s depictions of violence, such as the murder of Archbishop Oscar Romero, associate Jesus’s death with the violence inflicted upon the defenceless in contemporary Latin America by its ruling elites.

In Latin America, as Pérez Esquivel notes, peasants ‘battle for survival’ in the ‘wholesale eradication of subsistence farming and its replacement by agribusiness for export’ (Pérez Esquivel 1984: 92). Like scholars who interpret the parable of the wicked tenants as an argument against violence in the face of oppression, Pérez Esquivel calls for a nonviolent ‘battle’ against such unjust repression, one based on Jesus’s proclamation of good news to the poor and liberation of the oppressed (Luke 4:18–19).

References

McIntosh, Alastair. 2005. ‘Stations of the Cross from Latin America 1492–1992 by Adolfo Pérez Esquivel of Argentina’, www.alastairmcintosh.com, available at https://www.alastairmcintosh.com/general/1992-stations-cross-esquivel.pdf [accessed 20 April 2022]

Pérez Esquivel, Adolfo. 1984. Christ in a Poncho (Maryknoll: Orbis)

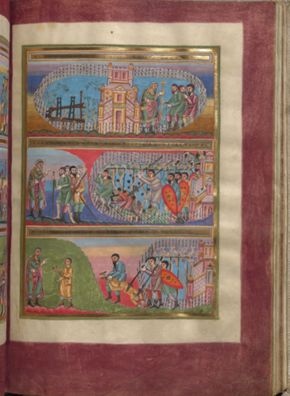

Unknown artist

The Wicked Tenants, from the Codex aureus Epternacensis, c.1030–50, Manuscript illumination, Germanisches National Museum, Nuremburg; Hs 156142 fol.157/77r, GNB Digitale Bibliothek: http://dlib.gnm.de/item/Hs156142/157

‘One born without fault was killed’

Commentary by David B. Gowler

This illumination begins with hope and ends in tragedy: a man plants a vineyard, not knowing that this planting will ultimately lead to the killing of his beloved son.

The inscription for the topmost of the illumination’s three tiers introduces the parable by saying that the vineyard was planted, and the image depicts the parable’s first verse (12:1): A fenced-in vineyard and wine press (labelled torcular) appear on the left; an elaborate watchtower (pl. turris) stands in the middle; and, on the right, the grey-haired and bearded landowner (pater familias) points to the vineyard as he makes the leasing agreement with three men (agricolae).

The second tier, whose title explains that the servants who were sent to collect the fruit were killed, collapses several scenes of the parable. On the left, the pater familias tells four servants (servi) to go and collect the produce, thus depicting in one scene what is in the parable the multiple sending of servants. The vineyard owner points to the vineyard, one servant looks at him intently, while the other three gaze in the direction of their future fates. At the right—in the vineyard whose vines have now produced abundant grapes—six tenants armed with spears, shields, and stones stab, beat, and stone the landowner’s servants. The servant with the bloody head is the second servant the landowner sent (12:4), the one who was ‘struck on the head’ and treated shamefully.

The bottom tier depicts two scenes from the last stages of the parable. On the left, the landowner tells his son (filius) to go to the vineyard. On the right, three tenants are killing the son. One drags him by his legs out of the vineyard, and two stab him with spears. The abundant grapes remain unpicked on their vines.

The title of this lower tier says that the son ‘born without fault’ was sent and was killed. Thus, the illumination visually narrates the allegory found in Mark 12: God sends prophets who are beaten and killed, and then God sends his ‘beloved son’ (Jesus, cf. Mark 1:11; 9:7; 12:6), who is also killed.

References

Gowler, David B. 2020 [2017]. The Parables after Jesus: Their Imaginative Receptions across Two Millennia (Waco: Baylor Academic Press)

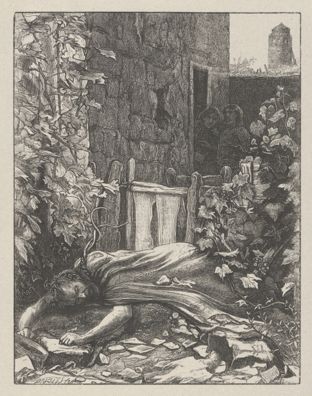

Brothers Dalziel, after John Everett Millais

The Wicked Husbandmen (The Parables of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ), 1864, Wood engraving; proof, Image: 139 x 109 mm; sheet: 186 x 154 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Rogers Fund, 1921, 21.68.4(8), www.metmuseum.org

‘A most sacrilegious murder’

Commentary by David B. Gowler

This wood engraving is from the Dalziel Brothers’ edition of The Parables of our Lord. It retains some of John Everett Millais’s early-career (pre-Raphaelite) concern for naturalistic detail—note the craftsmanship of the leaves and tendrils of the vines that Millais created ‘elaboratively from nature’ (Millais 1975 [1864]: xxviii). But it also merges figurative imagery with this exquisitely-crafted natural setting. The location is contemporary Scotland: the wall of the vineyard is a representation of a wall of Balhousie Castle in Perth.

Millais dramatizes the Gospel scene in which the tenants have seized the beloved son, killed him, and cast him out of the vineyard. The tendrils of the vine wrapped around the son’s neck direct our eyes to where the murderers stand in the shadows. They reveal not just that the man was murdered but also how and by whom. The men thus stand both literally and symbolically in darkness—looking at what they have done, their shaded faces concealing from us whether they feel remorse.

The dead man’s robe and fallen headband denote his elite status. A stone on top of the corpse, next to a broken-off and similarly lifeless leaf, may denote that the man was not only strangled but also stoned. The toad sitting on the dead son’s robe is often used in Christian art to portray the repulsive aspect of sin as well as symbolizing those who, like the tenants, seek after the fleeting pleasures or possessions of this world (Ferguson 1967: 4, 6).

Just below the body lies a dead dove. The multifaceted symbolism of doves in Scripture and art lends some ambiguity to its interpretation—doves can denote purity, innocence, peace, the Holy Spirit, and much more. When seeming to rise from the recently-deceased corpses of martyrs (see John William Waterhouse’s St Eulalia; 1885), they embody hope: their upward flights symbolize rebirth to everlasting life, of souls ascending to heaven.

Millais’s lifeless dove is in stark contrast to such images. It extinguishes, for the moment at least, whatever hope a live dove might provide and focuses attention instead on the man’s brutal death.

Yet for those interpreters who remember that turtledoves could be offered as sacrifices in the Temple (Leviticus 12:8; Luke 2:24), the dove perhaps intimates that this man’s tragedy may yet also be salvific. The evangelist’s own allegorical interpretation of this parable (Mark 12:10–11) implies no less.

References

Ferguson, George. 1967. Signs & Symbols in Christian Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Millais, John Everett. 1975 [1864]. The Parables of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ (New York: Dover)

Adolfo Pérez Esquivel :

7th Station of the Cross: The Land Question, 1992 , Acrylic [?]

Unknown artist :

The Wicked Tenants, from the Codex aureus Epternacensis, c.1030–50 , Manuscript illumination

Brothers Dalziel, after John Everett Millais :

The Wicked Husbandmen (The Parables of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ), 1864 , Wood engraving; proof

Precarious Tenancies

Comparative commentary by David B. Gowler

The parable of the wicked tenants in Mark 12:1–12 (parallels in Matthew 21:33–46; Luke 20:9–19) interweaves echoes from Jewish Scripture (Isaiah 5:1–7, which portrays God planting a vineyard, building a watchtower, and making a wine vat), allegory (the tenants symbolizing those who persecuted prophets and killed the ‘beloved son’, Jesus), and first-century socio-economic pressures (struggles over land and resources between non-elite tenants and wealthy, absentee landlords).

Later Christian interpreters elaborated extensively on the allegorical foundation laid by Mark. Irenaeus, for example, argued that the parable means that God rejected those who rejected the Son of God—those of the ‘former dispensation to whom the vineyard was formerly entrusted’—and gave the vineyard to Gentiles (the Church) who were formerly outside the vineyard (Against Heresies 4.36.1–4). Such supersessionism—the idea that Christians have replaced Jews as the ‘people of God’—is a problematic, anachronistic, anti-Jewish reading of the parable. It is entirely foreign to the historical Jesus, who proclaimed a renewal and restoration of Israel—a new leadership within Judaism, not an alternative outside of it.

Jesus was an impoverished, first-century Jew who was a member of a politically, militarily, and economically oppressed minority. Even if the parable includes some allegorical elements, it still evokes a first-century context in which an unjust redistribution of wealth by the elite forced many small independent landowners into being landless, dependent labourers. The worsening economic situation of numerous Galileans led to growing resentment against these landlords, and the economic hopelessness of the non-elite, including their inability to pay taxes to the rulers and pay off debts to the elite, was a central element of social conflict. Thus, this parable reflects a struggle over land and resources in which the wealthy elite relegated many non-elites to a bare subsistence level (Gowler 2012: 204–09). The later Gentile Christian church developed the parable into an anti-Jewish allegory, for example by explicitly stating that the owner (‘lord’; kurios) of the vineyard in the parable (Mark 12:9) symbolizes God (kurios; Mark 12:11).

Some scholars, then, evaluate the rebellion of the tenants as a desperate attempt to survive, one that continues an escalating spiral of violence that began with their oppression and results in their destruction. If this reading of the parable is accurate, then the owner of the vineyard does not symbolize God, and the parable urges Jewish ‘holy people of God’ not to respond to Roman exploitation ‘with hatred and violence’ but to work together in the Jewish tradition of nonviolent resistance (Schottroff 2006: 23–24; cf. Kloppenborg 2006).

The Golden Gospels of Echternach includes a full-page illumination of the parable of the wicked tenants, as well as full pages for three other parables, all of which involve socio-economic issues: the workers in the vineyard (Matthew 20:1–16), the great supper (Luke 14:16–24), and the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19–31; see Metz 1957, plates 67–70). The image of the wicked tenants is a ‘narrative type’ illumination, because it primarily follows the story found in the gospels—which already has allegorical elements—as distinct from ‘symbolic type’ illuminations that include extensive allegorical elaborations (cf. Mantas 2011: 214–15).

John Everett Millais’s The Wicked Husbandmen is one of twenty prints he created for The Parables of Our Lord (Millais 1975 [1864]). Unlike the Golden Gospel illumination, which portrays several scenes of the parable with explanatory written titles and labels, Millais’s print depicts one scene to stand in for the whole: a moment shortly after the murder of the son. It is more of an illustration—similar to his illustrations in novels (e.g., five novels of Anthony Trollope; Sanders 2001: 75)—rather than a visual commentary that leads to further contemplation of the parable’s mystery. Yet the image itself remains haunting, powerful, and evocative.

Strikingly, neither of the two artworks discussed above contains any hint of the tenants’ oppression or imminent destruction (Mark 12:9). Adolfo Pérez Esquivel’s Stations of the Cross, however, although it does not depict the parable, provides a mode of response to it—one espoused by Jesus—that, in Pérez Esquivel’s words, seeks ‘to achieve by nonviolent struggle the abolition of injustice and the attainment of a more just and humane society for all’ (Pérez Esquivel 1981: 106).

Pérez Esquivel’s Stations of the Cross thus modernizes Jesus and his message authentically, without, as Christian interpreters have tended to do over the centuries, domesticating Jesus—a first-century Jewish prophet of an oppressed people—or anachronizing his radical message.

References

Gowler, David B. 2012. ‘The Enthymematic Nature of Parables: A Dialogic Reading of the Parable of the Rich Fool (Luke 12:16–20)’, Review and Expositor, 109.2: 199–217

Kloppenborg, John. 2006. The Tenants in the Vineyard (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck)

Mantas, Apostolos. 2011. Die Ikonographie der Gleichnisse Jesu in der ostkirchlichen Kunst (5.-15. Jh.) (Leiden: Alexandros Press)

Metz, Peter. 1957. The Golden Gospels of Echternach (London: Thames and Hudson)

Millais, John Everett. 1975 [1864]. The Parables of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ (New York: Dover)

Pérez Esquivel, Adolfo. 1984. Christ in a Poncho (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books)

Sanders, Andrew. 2001. “Millais and Literature,” in John Everett Millais Beyond the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, ed. by Debra N. Mancoff (New Haven: Yale University Press), pp. 69–93

Schottroff, Luise. 2006. The Parables of Jesus (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress)

Commentaries by David B. Gowler