1 Kings 5; 2 Chronicles 2

The Matter of the Temple

Taddeo Gaddi

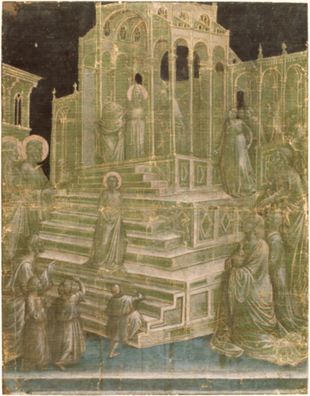

The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, c.1332, Tempera, pen and ink on green prepared paper, 366 x 285 mm, Musée du Louvre, Paris; MA12560, Photo: Richard Lambert © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Imagining the Temple

Commentary by Ruby Guyatt

By the 1340s, Taddeo Gaddi (c.1290–1366) was one of the most renowned painters in Florence.

This preparatory study would later form part of Gaddi’s main work, the Stories of the Virgin cycle, in the Baroncelli Chapel of the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence.

The study depicts an event recorded in the apocryphal Protoevangelium of James: Mary’s parents, Anne and Joachim, presenting their three-year old daughter in the temple at Jerusalem. The elderly couple were unexpectedly blessed with a child, and so offered her to God’s service as an act of thanksgiving. According to tradition, Mary remained in the temple until she was twelve, when she was entrusted to Joseph. She would herself be interpreted as temple-like, because her body would one day ‘house’ the divine presence. The feast of the Presentation of Mary is celebrated in the Catholic and Orthodox liturgical calendars.

The temple which Gaddi imagines in his study is the Second Temple, built c.537–16 BCE to replace Solomon’s original, which was destroyed in 586 BCE by King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon when he conquered Jerusalem. Nonetheless, the Second Temple—as well as the visual depictions, textual descriptions, and religious structures it has inspired—have repeatedly been celebrated as Solomon’s progeny, each fulfilling his promise ‘to build a house for the name of the Lord my God … as ordained forever for Israel’ (v.4). In her study of iconographies of the temple, architectural historian Amanda Lillie (2014) notes that Solomon’s original ‘was employed as a yardstick against which holiness, wisdom, and beauty were measured’, and that each rebuilding on the Temple Mount site kept its memory alive, ‘as the ancient core was subsumed within each new version’.

None of the plans for Solomon’s temple remain, and archaeological studies are mainly indirect and often contested. The scriptural descriptions of the temple (e.g. Jeremiah 19:14; 26:2; 1 Kings 6:17, 36; 2 Chronicles 3:5; 4:9) are also limited. Therefore, the artists who have depicted it and the architects who have evoked it in churches of their own design, have been left to imagine the space for themselves, often drawing on contemporaneous architectural and decorative styles.

Yet it never loses its power as an architectural and religious archetype, and the fact that Gaddi shows the full height of the temple—even at the risk of upstaging the actors and events it frames—suggests its undiminished importance for him.

References

Gardner, Julian. 1971. ‘The Decoration of the Baroncelli Chapel in Santa Croce’, Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte, 34.2: 89–114

Lille, Amanda. 2014. ‘Imagining the Temple in Jerusalem: An Archetype with Multiple Iconographies’, in Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting, on-line catalogue ed. by Amanda Lillie, available at https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/research/research-resources/exhibition-catalogues/building-the-picture/place-making/place-making-3 [accessed 3 March 2020]

Rhea Karam

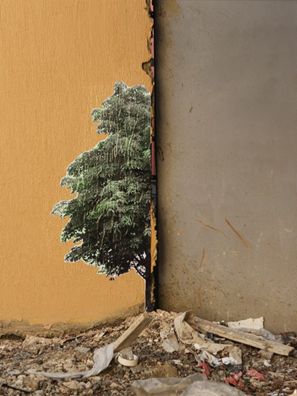

“TS_04”, 2015, Photograph; © Rhea Karam

Narrative Displacement

Commentary by Ruby Guyatt

The lives of the ancient Jews had been characterized by uncertainty. To this end, Solomon’s construction of the temple was both a building up, towards the heavens, and also a laying down of roots, for a people.

In fact, the temple would offer only a fragile and temporary security, witnessing repeated capture, plunder, destruction, and rebuilding. And yet despite—or perhaps because of—this, the temple narrative continues to occupy an important place in modern Jewish imaginations and identities.

The work TS_04 forms part of Rhea Karam’s 2015 series Déraciné (Uprooted). The Lebanese-born artist, who now lives in Brooklyn, photographed trees in New York’s Central Park, printed and painted the images, and transported them to Lebanon, where she ‘replanted’ them onto public walls in Beirut.

Once in Beirut, Karam ‘drove and walked around scouting for locations’, stopping ‘to paste once I found a wall that piqued my interest’ (Sharp 2017). Whilst Karam controlled the first part of the process from her New York studio, she has said of the uncertainty regarding replanting her trees on the streets of Beirut:

I did not know where they would end up exactly, but prepared them for their destination—similar to how we integrate into a new environment when we move countries, knowing where we are going but having a lot of uncertainty as to where, and if, we will fit in. (ibid)

Karam’s photographic uprooting and transplanting of New York oaks onto Lebanese walls inversely echoes Solomon’s sourcing of the timber for the temple in Jerusalem—‘cedar, cypress, and algum’—from Lebanon (2 Chronicles 2:8).

There are references to Lebanese cedar throughout the Hebrew Bible (e.g. Psalm 92:12; Ezekiel 31:3). Today the cedar tree appears on Lebanon’s flag and currency, a unifying emblem of a country whose sixteen-year civil war pitted various Christian military and political groups against the Palestine Liberation Organization, and Left-leaning Muslim political parties. The scars of the conflict can be seen on the walls onto which Karam pastes her trees

Meanwhile, Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, claimed by both Judaism and Islam, remains a focal point of the Arab–Israeli conflict. The temple which Solomon built to root one displaced people in ancient times has, in more recent history, been invoked in the displacement of another.

References

Karam, Rhea. 2018. ‘Déraciné’, available at http://www.rheakaram.com/dracin [accessed 3 March 2020]

Sharp, Sarah Rose. 2017. ‘A Show of Lebanese Art Suffused with the Longing of Exile, 2 May 2017’, www.Hyperallergic.com, [accessed 11 March 2020]

Rachel Kneebone :

399 Days, 2012–13 , Porcelain and mild steel

Taddeo Gaddi :

The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, c.1332 , Tempera, pen and ink on green prepared paper

Rhea Karam :

“TS_04”, 2015 , Photograph

A Temple for the Name of the Lord

Comparative commentary by Ruby Guyatt

2 Chronicles 2 begins: ‘Now Solomon purposed to build a temple for the name of the LORD, and a royal palace for himself’ (v.1).

What does it mean to build a temple for a name?

In the first instance, King Solomon’s phrasing complies with the reverent Hebrew convention of never directly speaking or writing God’s name.

But secondly, in building a temple for the name of the Lord, Solomon builds a specific sort of temple. Several verses later he asks rhetorically: ‘who is able to build him a house, since heaven, even highest heaven, cannot contain him?’ (v.6). In building his temple, Solomon is not trying to contain or confine God in timber, precious metals, and stone—sourced and shaped by human hands. Instead, this temple is to be an architectural act of praise, a space for human hearts to be moved by God, and for human voices and gestures to honour and thank him: ‘Who am I to build a house for him, except as a place to burn incense before him?’ (v.7).

For the writer of 2 Chronicles, establishing the temple is central to Solomon’s life and reign. After recording only briefly Solomon’s pursuit of wisdom and his military and commercial activity in 2 Chronicles 1, the Chronicler dedicates six chapters (2 Chronicles 2–7) to Solomon’s preparing, constructing, furnishing, and dedicating the temple. The temple has here the sort of literary centrality that its successor will have visually in Taddeo Gaddi’s early fourteenth-century fresco in the church of Santa Croce.

In building the temple, Solomon fulfils the vision, hope, and work of his father, David. At the end of 1 Chronicles, an ageing King David instructs Solomon that it is his divine purpose to build the temple for which David had begun preparing (1 Chronicles 28). Solomon takes his father’s dying instruction seriously; in 2 Chronicles 2 he recalls his father’s words (v.3), deals with and employs the same artisans as David had (vv.8, 15), and uses the census that David had taken of alien labourers (v.17). The centrality of the construction of the temple to Solomon’s identity is acknowledged by those around him. King Huram of Tyre, who provided first David and then Solomon with the materials and craftspeople for the temple, thanks God for giving ‘King David a wise son, endued with discretion and understanding, who will build a temple for the LORD, and a royal palace for himself’ (v.12).

The temple is existentially significant not only individually, to Solomon, but collectively, to Israel. Built nearly 500 years after they had been delivered out of Egypt (1 Kings 6:1), Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem was the first temple the Israelites, ‘his people’ (2 Chronicles 2:11), built for their God. The temple represented a space not only of worship, but of belonging—a symbolic home for a displaced people, a living monument to God’s covenant and divine indwelling with Israel.

Although Solomon built his temple for the God of Israel, he went in search of the best materials and men. The cedar trees he used (vv.3, 8; cf. 1 Kings 5:8–10) were the finest timber, sourced from the neighbouring north. To secure them, he was prepared to uproot and transplant, in a fashion recalled by the ‘cutting’ and ‘pasting’ of trees by contemporary Lebanese artist Rhea Karam, in her explorations of identity, diaspora, and displacement.

And (in a detail unique to the Chronicles account) Solomon used the most expert artisans and labourers from both inside and outside Judah (2 Chronicles 2:7–10). In mentioning Solomon’s recourse to foreign expertise and labour, the Chronicler, unlike the author of 1 Kings, suggests that whilst this was a temple built to honour the name of the God of Israel, its importance and effects had far wider ramifications. The First Temple was the work of both Jewish and Gentile materials and hands. Its significance beyond the people of Israel is confirmed by the way it has become an enduring component of diverse religious imaginaries—hence its centrality to Gaddi’s fresco in Florence (a city imagined by many Florentines of the time as a new Jerusalem).

Solomon’s temple would be only a temporary monument to the everlasting glory of his God; in 587 BCE it was destroyed by the Babylonians, and its successor was obliterated by the Romans in 70 CE. Like the fractured Beirut walls on to which Karam has pasted her works, Jerusalem’s temples, too, have spoken of the vulnerability of human designs. And this is something which we also glimpse in the deliberate ruptures of Rachel Kneebone’s epic porcelain column, 399 Days.

But while the bricks, beams, and decorations of the temple would be turned to dust, the name for which it was built continues to echo throughout the earth—in works, words, and communities.

References

Dozeman, Thomas B. 2017. The Pentateuch: Introducing the Torah (Minneapolis: Fortress Press)

Selman, Martin J. 2016. Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries: 2 Chronicles (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press)

Commentaries by Ruby Guyatt