Ruth 3–4

New Life from Outside

Güler Ates

Isimsiz, 2008, Archival Digital Print, 51 x 51 cm, Collection of the artist; © Guler Ates, courtesy of Bridgeman Images; Photo: courtesy of the artist

An Elusive and Ambiguous Woman

Commentary by Susanna Snyder

A twenty-first century woman covered in brightly coloured lace and silk climbs a staircase in Leighton House, Kensington—the residence, in the nineteenth century, of Frederic, Lord Leighton.

Lord Leighton collected Middle Eastern artefacts to display in his London home. In her work Isimsiz the London-based Turkish artist Güler Ates highlights the juxtaposition of Eastern and Western cultures that resulted. Her photograph shows an Iznik hexagonal tile (c.1530) behind the banister and a peacock in front of it. Both of them reflect a Victorian notion of—and a colonially-influenced taste for—the exotic.

Veiled women drawn in Lord Leighton’s sketchbook struck Ates as particularly ‘exoticising images’ (Ates 2019). She toys with such images here. But the woman cannot be pinned down. While her head and face—parts of the body often associated with subjectivity and identity—are missing, her upward movement indicates her self-possession, power, and determination to move towards an undetermined destination. Her mystery is not imposed. It is not a fantasized otherness —a kind of dubious orientalizing mystique. Rather, the woman refuses to allow others to fully see and thereby objectify her.

Like the woman in Isimsiz, Ruth cannot be captured. Her portrayal is full of paradoxes, explaining why she has been characterized differently by biblical scholars (e.g. LaCocque 2004; Sakenfeld 1999; Donaldson 2010).

She is defined repeatedly as a Moabite—a foreigner from an enemy nation—but is hailed as a ‘worthy woman’ by Boaz (3:11) and affirmed as being worth more than seven sons to Naomi (4:15). (Seven was the number associated with perfection.)

She seems to find her voice in chapter 3 (v. 9; 16–17) but later returns to silence, is ‘acquired’ by Boaz (4:10) as property, and has her child, Obed, taken from her by Naomi (4:16).

She is submissive and obeys orders. But she is also feisty and courageous, risking social ostracisation to proposition Boaz on the threshing-floor (Nielsen 1997: 70; Koosed 2011: 73).

Who is Ruth? Does her character kowtow to patriarchal and colonial insistence that women’s—particularly foreign women’s—value is only to be found in marriage and bearing children for the nation? Is she a ‘model minority’ who is exploited as a source of social and economic capital? (Yee 2009:128–34). Or, do we glimpse in these chapters of the Bible a subversive divine affirmation of her creative resilience, self-sufficiency, shrewdness, and love?

References

Conversation with Güler Ates, 24 June 2019.

Donaldson, Laura. 2010. ‘The Sign of Orpah: Reading Ruth through Native Eyes’, in Hope Abundant: Third World and Indigenous Women’s Theology, ed. by Kwok Pui-Lan (Maryknoll: Orbis), pp. 138–51

Koosed, Jennifer L. 2011. Gleaning Ruth: A Biblical Heroine and Her Afterlives (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press)

LaCocque, André. 2004. Ruth, trans. by K. C. Hanson (Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress)

Nielsen, Kirsten. 1997. Ruth (London: SCM Press)

Sakenfeld, Katharine Doob. 1999. Ruth (Louisville: John Knox)

Yee, Gale A. 2009. ‘“She Stood in Tears Amid the Alien Corn”: Ruth, the Perpetual Foreigner and Model Minority’, in They Were All Together in One Place? Toward Minority Biblical Criticism, ed. by R. C. Bailey, T. B. Liew and F. F. Segovia (Atlanta: SBL), pp. 119–40

Mona Hatoum

Impenetrable, 2009, Steel and Nylon monofilament, 300 x 300 x 300 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Purchased with funds contributed by the Collections Council and the International Director's Council, with additional funds from Ann Ames, Tiqui Atencio Demirdjian, and Marcio Fainzilber, 2012, 2012.10, © Mona Hatoum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation / Art Resource, NY

Borders and Boundaries

Commentary by Susanna Snyder

Impenetrable confuses. The cube formed by suspending barbed wire rods from the ceiling seems simultaneously fragile and intimidating. The thinness of the wires invites entry into the spaces between them while their spiky danger makes this impossible. We look on, stuck, perhaps wanting to explore the cube from within but scared and unable to do so.

Artist Mona Hatoum was born in Beirut to Christian Palestinian parents, and she has lived in London since 1975. Her work often emerges from her own experience of exile, and grapples with ambiguity and paradox. Impenetrable provokes consideration of structures that seek to confine and deter, enclose and repulse at the same time—edifices such as fences, camps, and detention centres (Hinkson n.d.)

If the twentieth century was one of growing global connectivity, the twenty-first century has so far been defined by the reassertion of national borders and identities in much of the Global North, and elsewhere too. Barbed wire fences, walls, and migrant camps have been constructed within and at the edges of Europe and North America (Schain 2018; Bieber 2018). These have been designed to contain people. They have also aimed to deter other would-be migrants from making the journey. Numerous commentators are suggesting that free-market, cosmopolitan optimism about the endless possibilities that could result from overcoming distance and difference has dissolved for many in Western capitalist economies into something else: a desire to restore an imagined bounded national past. Simultaneously, though, the promise of what lies beyond the boundary—safety, a move away from poverty, hope—continues to draw people to seek ways around or over them.

Beginning with the departure from Judah to Moab by Naomi, Elimelech, and their two sons, the book of Ruth is imbued with borders and boundaries. They are woven throughout the narrative and bifurcate the characters. When Ruth accompanies Naomi back from Moab to Judah, she crosses not just a geographical border but a cultural and a religious one. It is a border she must continue to negotiate in chapters 3–4, for she never escapes the label ‘the Moabite’ (4:5, 10). Gender boundaries also come to the fore with the distinct familial, sexual, economic, and legal roles of women and men of the time both highlighted and challenged.

Like the barbed wire of Hatoum’s structure, these boundaries have a power of resistance that is belied by their self-effacing delicacy. They may be unobtrusive but they are dense.

References

Bieber, Florien. 2018. ‘Is Nationalism on the Rise? Assessing Global Trends’, Ethnopolitics 17.5: 519–40

Hickson, Lauren. n.d. ‘Mona Hatoum: Impenetrable’, www.guggenheim.org [accessed 20 January 2020]

Schain, Martin. 2018. Shifting Tides: Radical-Right Populism and Immigration Policy in Europe and the United States (Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute)

Ibrahim El-Salahi

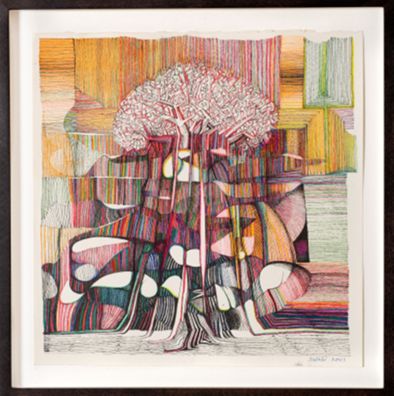

The Oxford Tree, 2001, Pen, ink, and coloured ink on Bristol board, 34 x 34 cm, Private Collection, London; © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London; Photo: Courtesy of Vigo gallery and the artist

Signs of Life

Commentary by Susanna Snyder

Obed is celebrated as ‘a restorer of life and a nourisher’ of Naomi’s old age (Ruth 4:15 NRSV). The genealogy listing his son and grandson as Jesse and David (4:22) and the connecting of Ruth with Rachel and Leah (4:11) reveal Obed’s importance in the renewal and sustenance of Israel. Ruth is the great-grandmother of the renowned King David, and through him, for Christians, an ancestor of Jesus the Messiah.

More immediately in the narrative, Ruth also bears smaller gifts to those around her. She offers Naomi six measures of barley given to her by Boaz. Ruth is a life-bringer, hope-bringer, and God-bearer. She nurtures and revivifies individuals, community, and the whole people of God.

Trees are often imbued in religious and indigenous traditions with sacred meaning—frequently symbolizing life and growth. They are one of a number of significant motifs that recur in the work of Ibrahim El Salahi. El Salahi uses the ‘abstracted motif of the tree … as a metaphorical link between heaven and earth, creator and created’ (Fritsch 2018: 10). A Muslim Sudanese refugee living in Oxford, he combines European forms and Sudanese themes. His work has variously been described as transnational surrealism and African or Arab modernism. He has a particular interest in the haraz tree, depicted here in The Oxford Tree. An acacia indigenous to Sudan that grows in the Nile valley, El Salahi sees it as ‘a symbol of the Sudanese and their resilience’. The haraz is bare in rainy season when everything else is green. It blooms during the dry season when all else is stripped. It is ‘a very obstinate tree, just like the Sudanese’. Finding the tree within as well as outside himself, he notices it ‘trying to assert itself’ (Fritsch 2018: 24, 55).

Ruth asserts herself both by her entry into and after her arrival in Israel. In doing so, she blooms at a time when the community of Israel is struggling and dry. One possible Hebrew root of her name is rwh, meaning to water to saturation (Donaldson 2010: 146).

References

Donaldson, Laura. 2010. “The Sign of Orpah: Reading Ruth Through Native Eyes”. In P-L. Kwok, (ed.), Hope Abundant: Third World and Indigenous Women's Theology: 138-151. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis.

Fritsch, Lena. 2018. Ibrahim El-Salahi: A Sudanese Artist in Oxford (Oxford: Ashmolean Publications)

Güler Ates :

Isimsiz, 2008 , Archival Digital Print

Mona Hatoum :

Impenetrable, 2009 , Steel and Nylon monofilament

Ibrahim El-Salahi :

The Oxford Tree, 2001 , Pen, ink, and coloured ink on Bristol board

Transgression to Transformation

Comparative commentary by Susanna Snyder

The brevity of the book of Ruth belies its significance. It offers an answer to some of the most important questions the people of Israel grapple with throughout the Old Testament. How are we to respond to outsiders? How should we understand and inhabit boundaries? Are we allowed to transgress them? Mona Hatoum, Güler Ates, and Ibrahim El Salahi grapple with similar questions in the contemporary context.

While its date is disputed, Ruth was written at a time of precarity. If authored before the Israelites’ sixth-century BCE experience of exile, this was because of threats to the Davidic monarchy. If post-exilic, this was because people were trying to come to terms with the profound trauma of forcible displacement.

Uncertainty and fear tend to provoke concern about identity and material resources, and an ongoing debate concerning how to respond to those defined as ‘other’ to Israel rumbles on behind this text. Who was to be included and given access to the holy places and rights to land, wealth, and power? Who should be legitimately excluded? How tightly were boundaries to be drawn between ‘us’—Israelites, the people of God—and ‘them’—the others, foreigners? Can we intermarry with outsiders or will they pollute and threaten us?

Two trajectories of response solidified over time. One urged exclusivity. We glimpse it in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, where intermarriage is condemned and foreigners are prohibited from entering the Temple. Another urged inclusivity. It encouraged care to be offered to the alien and hospitality to be showed to the stranger (e.g. Leviticus 19:33–34). It envisaged the mountain of the Lord being one to which all people and nations of the world would come and dwell together (Isaiah 55–56). The book of Ruth epitomizes this second strand.

Ruth—the book and the character—interrogates and transgresses borders. Borders create others, and Ruth is the ultimate outsider. She dwells on the wrong side of religious, cultural, and social boundaries of her time. Moab was considered to be an archenemy of Israel, as the Moabites had refused to help the people of Israel on their way to the Promised Land (Deuteronomy 23:4) and Moab was born through an incestuous relationship between Lot and his daughters (Genesis 19:36–37). Also, Ruth is a woman, and—what is more—a childless widow at a time when being barren was a sign of divine disfavour.

Hatoum’s Impenetrable evokes the stark inhospitality that outsiders like Ruth—past and present—must overcome. It is an inhospitality which eats away at the space it purports to protect even as it is projected outwards, for the barbed wire borders do not just demarcate the cube’s edges. They constitute the cube. Borders become, so to speak, all that the cube is. So too the costly navigation of—and tripping up on—hostile borders can imbue the lives of migrants long after the physical crossing of a particular nation state line is over. And this infects the lives and experience of non-migrants dwelling in these spaces too.

But Ruth transgresses boundaries to become an agent of transformation. Through bearing Obed, she brings joy to Boaz and fills Naomi’s emptiness (4:13–17) and Obed’s name, meaning serving, underlines his role in God’s salvific plan. Ruth also encourages Boaz, and through him the broader community of Israel, to enlarge his understanding of the Torah law concerning the role of the kinsman redeemer (go’el) and the inclusion of outsiders. As Bergant puts it:

[t]he strange and potentially dangerous woman has become the agent of God’s salvation … the blessing of salvation comes from without (God) not from within (ourselves). (Bergant 2003: 52, 60)

The borders so menacingly evoked in Impenetrable—the vertical barbed wires that exclude and harm those that seek to pass by, over, or through them—turn metaphorically, then, into the life-giving vertical lines of El Salahi’s The Oxford Tree. His lines connect earth and heaven, transgressing the boundary between mundane and holy, to form the haraz tree that bursts with vivacity unexpectedly when all else has dried up around it. Just as El-Salahi’s tree fuses the vegetation and colours of Sudan with Western modernism—blending cultural, national, and aesthetic categories—so Ruth’s hybridity and boundary-crossing are the source of new life for Israel. She is like the woman in Ates’s Isimsiz. Resisting being fully known by others, Ruth’s gift begins with her otherness, courage, and movement. Both The Oxford Tree and Isimsiz suggest the strength and possibility that can come from without.

While human beings in their full subjectivity are noticeably absent from the three works of art, Ruth 3–4 is full of them. Fifty-five out of eighty-five verses in Ruth are spoken conversation, which is the highest proportion of dialogue to narrative in any biblical book (Sasson 1997: 320). Human relationship and conversation is where the key work of transgression towards transformation takes place. And it is through this presence of the characters to one another that God’s presence is made manifest.

References

Bergant, Dianne. 2003. ‘Ruth: The Migrant Who Saved the People’, in Migration, Religious Experience, and Globalization, ed. by G. Campese and P. Ciallella (New York: Center for Migration Studies), pp. 49–61

Sasson, Jack. 1997. ‘Ruth’, in The Literary Guide to the Bible, ed. by R. Alter and F. Kermode (London: Fontana), pp. 320–28

Commentaries by Susanna Snyder