Jonah 3

Nineveh Relents

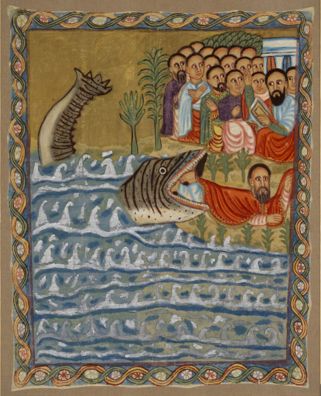

Unknown Ethiopian artist

Jonah and the Whale, 1940–45, Oil on canvas, 200 x 162.2 cm, The British Museum, London; Af2006,22.3, ©️ The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Fishy Empire

Commentary by jione Havea

An artwork can put an entire story on one page. But there is only so much that a page can take, and artists are selective about who and what they foreground or ignore.

In this Eritrean painting from the 1940s, by an Ethiopian priest whose name is not known, Jonah slides out of the mouth of the fish. He has a smooth landing, with his hair, beard, and clothes in place. The tail of the fish stands up like the tower of a castle, as if to suggest that the fish stands in for the empire. This work lets Nineveh off the hook, so to speak (see also, Lindsay 2016).

The power (read: effect of being in the belly) of the empire (fish) did not affect Jonah. He slides out of the empire and goes into the city where he sits to preach, from a text. He has words, and his audience are groomed and priestly. They are all men, with eyes wide open, and their arms, crossed over their chests, suggest reverence, not wariness or resistance (as folded arms can sometimes do). There is no hint of wickedness in Jonah’s audience. Nineveh was not wicked; the people of Nineveh did not need to repent.

This painting is about ‘men’s secret business’, to borrow a phrase from Indigenous Australians. Men’s secret business has to do with ceremonies, rituals, and rites of passage. Men in all cultures have secret business, and i wonder if the Ethiopian artist had something Ethiopian in mind to add to the biblical narrative.

There are plants in this work which, with the sea, are critically needed in modern carbon-producing civilizations. Could these plants be evidence of something Ethiopian (as asked above): symbolizing something meaningful in an Ethiopian context?

There are no women, children, or animals in this painting. I wonder if they have been drowned by the sea, which takes up more than half of the painting. Such a view of the sea is not so strange in our climate-changed world, where women, children, and animals are at the frontline of climate crises (see also, Elvey 2016).

References

Elvey, Anne. 2016. ‘Complex Anachronism: Peter Porter’s Jonah, Otherkind, Ancient and Contemporary Tempests, and the Divine’, The Bible & Critical Theory, 12: 79–93. Available at https://www.bibleandcriticaltheory.com/issues/vol12-no1-2016/vol-12-no-1-2016-complex-anachronism-peter-porters-jonah-otherkind-ancient-and-contemporary-tempests-and-the-divine/ [accessed on 31 July 2023]

Lindsay, Rebecca. 2016. ‘Overthrowing Nineveh: Revisiting the City with Postcolonial Imagination’, The Bible & Critical Theory, 12: 49–61. Available at https://www.bibleandcriticaltheory.com/issues/vol12-no1-2016/vol-12-no-1-2016-overthrowing-nineveh-revisiting-the-city-with-postcolonial-imagination/ [accessed 31 July 2023]

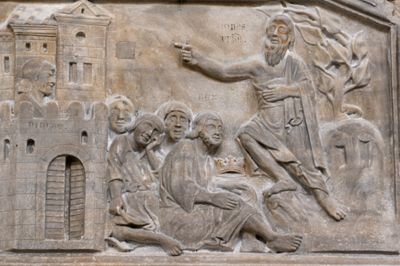

Unknown Italian artist

Jonah and the City of Nineveh, 13th century, Stone relief, Cathedral of Sessa Aurunca, Campania; akg-images / De Agostini / V. Giannella

Hinterland

Commentary by jione Havea

In this relief from the Sessa Aurunca Cathedral, Campania (Italy), Jonah’s right finger ‘preaches’ at the empire, as represented by a walled city at left. A man, who is not pointed out by Jonah’s finger, rises above the wall. Is this man, who could be the king in the biblical narrative, listening to Jonah or staring him down? There is no connection between the two men, and there is no feeling of urgency.

This relief could be referencing two instances in the biblical narrative: first, it could be referring to Jonah preaching against the city (3:4); second, it could also be referring to Jonah arguing with God on account of the city (4:1–4). The first was after Jonah arrived; the second was just before Jonah left the city (4:5).

The gate is open, and Jonah is outside the city. But he is not far off. At his feet, an audience—some of whom could be women—appears bored. They don’t look at Jonah. They also look past us, the viewers of this relief. They are there, and not there. They fill the space between where Jonah was, east of the city (4:5) and the city itself. They testify that the hinterland is not empty (see Manoa 2010).

Behind Jonah is a booth and a creeping plant that—in the biblical narrative—gave him comfort after he left the city (4:6). The Qur'an, by contrast, relocates the plant to the ‘wide bare tract of land’ (37:145) where the fish vomited Jonah out—a moment before he enters that city. The plant moves from providing relief to an angry prophet in the biblical narrative, to providing an opportunity for a fishy prophet to rest up and recover in the Qur’anic version (see Havea forthcoming).

Scriptures move details around, as the Qur’an does to the slender plant in the hinterland of the biblical narrative (and, among many other examples, as the Gospel of John does to the so-called Synoptic Gospels). And so do readers—we move and ignore narrative details in the interests of the readings that we favour.

References

Havea, Jione. Forthcoming. ‘Would Vishnu save Jonah’s Poor Fishie? A Transtextual Query’, in Queering the Prophet: On Jonah, and Other Activists, ed. by L. Juliana Claassens et al (London: SCM)

Manoa, Pio. 2010. ‘Redeeming Hinterland’, The Pacific Journal of Theology 2.43: 65–86

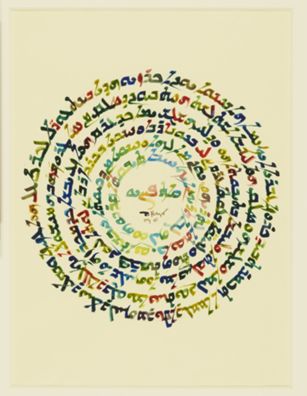

Behnam Keryo

Calligraphy in Aramaic script recounting Jonah's preaching to Nineveh, 2006, Ink on paper (?), 300 x 420 mm, The British Museum, London; 2013,6026.2, ©️ Family of Behnam Keryo; Photo: ©️ The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Words Can Kill, Words Can Also Save

Commentary by jione Havea

She got upset, such the sea, by Jonas who came up from the sea. She was struck by big waves as the tides striking the sea. Jonas went down to the sea and troubled it and came up to the land and upset it. The sea was troubled when he ran away, and the land was disrupted when he preached. The sea calmed down by the prayer and the land by the repentance. He prayed in the belly of the big fish and the Ninivites prayed in the mighty citadel. The prayer saved Jonas and the prayers saved Ninivites. Jonas ran away from God and the Ninivites, from purity. The justice locked them both like culprits. Both repented and were saved. (English translation of Aramaic script by Behnam Keryo)

Calligraphy is art, and Behnam Keryo’s work is art that disturbs. The calligraphy uses Aramaic words, the language of Nineveh—Keryo’s homeland—so one should read from right to left. But where should one begin to read Keryo’s script? The calligraphy forms six free-standing circles, as if they are ripples—but do they ripple inward, or outward?

Keryo’s work invites viewers to imagine the confusion that was caused by Jonah’s five Hebrew words intended for Nineveh. I imagine that Jonah’s words traumatized the people of Nineveh (see Boase & Agnew 2016) and moved them to act decisively.

Keryo provided an English translation of his Aramaic script (full text above): Jonah disturbed both the sea (by his presence) and the land (by his preaching); the sea calmed down because of Jonah’s prayer (of words, in Jonah 2), and the land by the people’s repentance (with purpose). In Keryo’s script, words saved both Jonah (in the sea) and the people of Nineveh (on land).

I come from a sea of islands—Oceania, Pacific Islands, Pasifika—where listening to the voices and interests of the sea and of the (is)lands is natural. For instance, the Tongan poet Kuini Salote III wrote songs in which she gave expression to the ‘voice of the wave’ (si‘i le‘o e peau) and the ‘voice of nature’ (si‘i le‘o ‘o natula).

I am grateful that the late Keryo of Nineveh (modern-day Iraq) and the late Kuini Salote of Tonga heard voices and words that scriptural texts ignored (see also Havea 2020).

References

Boase, Elizabeth and Sarah Agnew. 2016. ‘“Whispered in the Sound of Silence”: Traumatising the Book of Jonah’, The Bible & Critical Theory, 12: 4–22. Available at https://www.bibleandcriticaltheory.com/issues/vol12-no1-2016/vol-12-no-1-2016-whispered-in-the-sound-of-silence-traumatising-the-book-of-jonah/ [accessed on 31 July 2023]

Havea, Jione. 2020. Jonah: An Earth Bible Commentary (London: Bloomsbury)

Unknown Ethiopian artist :

Jonah and the Whale, 1940–45 , Oil on canvas

Unknown Italian artist :

Jonah and the City of Nineveh, 13th century , Stone relief

Behnam Keryo :

Calligraphy in Aramaic script recounting Jonah's preaching to Nineveh, 2006 , Ink on paper (?)

Jonah, a Moving Story

Comparative commentary by jione Havea

In the Qur'an, Yunus (Jonah) did not preach. Nineveh did not need to be preached against. Without Jonah saying a word, the people believed, and Allah let them enjoy life for a while (Surah 37:147–148).

In the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible, meanwhile, Jonah preached five Hebrew words to announce impending doom upon Nineveh (3:4 NRSV). But the king and people of Nineveh ‘believed God; they proclaimed a fast, and everyone, great and small, put on sackcloth’ (3:5). Their aim was to make God relent, so that they would not perish (3:9). And it worked. God relented (3:10). Nineveh’s people saved themselves on account of their accepting words, purposeful actions, and renewed hearts.

A short story like Jonah, with its performative actions (see Mathews 2016) and shifting plot (see Rees 2016), invites readings that move and relocate details, and readings that juxtapose the biblical narrative with other texts (see Havea 2016; Kunz-Lübcke 2016). Those readings are normal, i argue, despite the obsession of biblical scholars with being ‘faithful to the text’. What does it mean to be faithful to a text, when the plot of that text is selective and relenting (pun intended) in the first place?

My readings of the three artworks with Jonah 3 showed that artists too move details around. The plants in the Eritrean painting remind me of the slender plant that the Qur'an moved from the hinterland (in the Hebrew narrative) to the shore. The artist was a Christian priest, but his work makes room for the Qur'an.

In the cathedral relief, a plant shades Jonah; in the Eritrean painting, plants fill the space between the sea and the city. The plants in the Eritrean painting serve the function of Jonah’s audience in the cathedral relief: the audience and the plants show that narrative spaces are peopled and ‘planted’. In other words, these artists see something that readers of biblical texts fail to see.

The plants in the cathedral relief and the Eritrean painting invite another reading of Behnam Keryo’s calligraphy. In my first reading, shaped by my worldviews as a saltwater native, i saw ripples. But i am also a native of dry (is)land, and the calligraphy may also be seen as a canopy. While the other two artworks look at plants from the side, Keryo’s calligraphy invites us to look at plants from above as well.

This second reading affirms Keryo’s concern for calm in the sea and over the land, a calm that is possible when the plant world is seen and affirmed from all sides. In the biblical and Qur'anic texts, the plant serves the interest of Jonah. In the juxtaposition of the three artworks in this reflection, the plant world serves the interests of the sea and of the land. In other words, we humans need to look beyond the breaths upon our noses.

As a biblical and cultural critic, i value the ways in which these artworks challenge me to rethink the connection between scriptural texts and interpretations. I was trained to privilege the ancient text, but i have learned that scriptures negotiate, and textual details move; furthermore, interpretations evolve and relent. Keryo did another calligraphic work (2006), using Aramaic text by St Ephrem of Nisibis (also known as Ephrem the Syrian; 306–73 CE), which partly seems to lay the blame for Nineveh’s judgement on its beautiful women. Nineveh was saved because ‘the impertinents have weaned their eyes to observe not women’ (Keryo 2006).

I do not know which calligraphy was made first, but they may illustrate ‘relenting’ in the work of one artist. While one work (that partly lays the blame on beautiful women) is an example of ‘men’s business’, the other work relents that testosterone-filled stance with a sea-and-land-affirming script(ure).

Against the testosterone-filled and classist—for the audience are men of the cloth—stance of the Eritrean painting, the cathedral relief puts women who are not interested in Jonah’s preaching before viewers and worshippers. These two artworks appeal to different sides of the pulpit, where men too are not interested in the preached words.

In closing, i wonder: how might the artists who created these three works add the fasting animals (3:7–8) to their artworks? When humans fast, the animal and plant worlds have a chance to relax … and calmness becomes more possible for the sea and the (is)land.

References

havea, jione. 2016. ‘Sitting Jonah with Job: Resailing Intertextuality’, The Bible & Critical Theory, 12: 94–108. Available at https://www.bibleandcriticaltheory.com/issues/vol12-no1-2016/vol-12-no-1-2016-sitting-jonah-with-job-resailing-intertextuality/ [accessed 31 July 2023]

Kunz-Lübke, Andreas. 2016. ‘Jonah, Robinsons and Unlimited Gods: Re-reading Jonah as a Sea Adventure Story’, The Bible & Critical Theory, 12: 62–78. Available at https://www.bibleandcriticaltheory.com/issues/vol12-no1-2016/vol-12-no-1-2016-jonah-robinsons-and-unlimited-gods-re-reading-jonah-as-a-sea-adventure-story/ [accessed 31 July 2023]

Mathews, Jeanette. 2016. ‘Jonah as a Performance: Performance Critical Guidelines for Reading a Prophetic Text’, The Bible & Critical Theory, 12: 23–39. Available at https://www.bibleandcriticaltheory.com/issues/vol12-no1-2016/vol-12-no-1-2016-jonah-as-a-performance-performance-critical-guidelines-for-reading-a-prophetic-text/ [accessed 31 July 2023]

Rees, Anthony. 2016. ‘Getting Up and Going Down: Towards a Spatial Poetics of Jonah’, The Bible & Critical Theory, 12: 40–48. Available at https://www.bibleandcriticaltheory.com/issues/vol12-no1-2016/vol-12-no-1-2016-getting-up-and-going-down-towards-a-spatial-poetics-of-jonah/ [accessed 31 July 2023]

Commentaries by jione Havea