Acts of the Apostles 12

Peter’s Escape from Prison

Asako Narahashi

Kawaguchiko, from the series Half Awake and Half Asleep in Water, 2003, Chromogenic print, 90 x 135 cm; © Asako Narahashi; photo courtesy PRISKA PASQUER, Cologne

A Different Perspective

Commentary by Rebecca Dean

Peter went out and followed him; he did not realize that what was happening with the angel’s help was real; he thought he was seeing a vision. (Acts 12:9)

They said to her, ‘You are out of your mind!’ But she insisted that it was so.… [W]hen they opened the gate, they saw him and were amazed. (vv.15–16)

The story of Peter’s prison escape is one in which initial assumptions are challenged and transformed, not only for the characters in the story (as in the quotations above), but also for the readers. What does it take to make us see the world differently?

This idea of shifting perceptions is captured in the image from Tokyo-based photographer Asako Narahashi (b.1959). It is part of a series entitled 'Half Awake and Half Asleep in the Water' (2001–08). All of the photographs within the series are created by partially submerging the camera lens in water and shooting images of the land or sky from this viewpoint.

Narahashi has described the distancing effect of this approach and the memories it initially evoked for her of swimming in the sea as a child while watching her parents on the beach. There was a desire to return to them, and yet also an awareness that it felt good to be in the water. Following the 2011 tsunami and earthquake, and the resulting nuclear disaster at Fukushima, these images of partial submersion took on a more complex set of meanings as an unsettling reminder of the power of the natural world.

The title of the image Kawaguchiko refers to the lake in which the photograph was taken. It is one of the five lakes at the foot of Mount Fuji, and the peak of the mountain is visible within the frame. In spite of this majestic backdrop, the camera focus is on the water line, creating a sense of distortion and offering a new perspective upon the landscape.

This idea of new perspective is an enduring theme in the Acts of the Apostles, which grapples with the upside-down standards of the Kingdom of God, where the last will be first and the powers of the present age can be overcome (Acts 2:17; 17:1–9). In Acts 12, both Peter’s escape and King Herod’s sudden death bear witness to these unexpected realities.

References

Grow, Krystal. 2014. ‘Eerie Photos of Japan’s Coast’, TIME Lightbox https://time.com/3600559/eerie-photos-of-japans-coast/ [accessed 15 May 2020]

Rowe, C. Kavin. 2009. World Upside Down: Reading Acts in the Graeco-Roman Age (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. 2018. ‘Asako Narahashi’s Photos from the Sea’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMvpUnp1Cnc&vl=en [accessed 13 May 2020]

Unknown Chinese artist

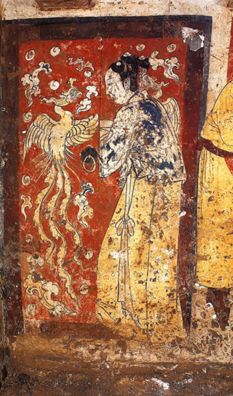

Woman opening a phoenix-painted door, tomb of Zhang Shiqing, c.1093–1117, Painted wood, Xuanhua, Hebei; Pictures from History / Bridgeman Images

Standing at the Threshold

Commentary by Rebecca Dean

Zhang Shiqing was a devout Buddhist and senior official who lived in north-western China during the later years of the Liao Dynasty (c.907–1125). His tomb consists of a square antechamber connected via a short-arched hallway to the main (rear) chamber, where his remains were housed. It is part of a family cemetery in the village of Xiabali, and it is decorated with lime plaster and mineral pigment murals, inscriptions, and celestial maps.

As is common within the tombs of this period and place, the interior is a microcosm of the universe, with signs of the zodiac painted on the ceiling, and scenes from everyday life adorning the walls. Activities associated with the rising sun are depicted on the eastern walls, while those that take place in the evening can be found on the western walls. Women are commonly included within the images in the rear chamber, and they may have represented the domestic servants who were to take care of the deceased. When these women are portrayed opening or closing a door, they are always painted with their back to the viewer, looking out rather than in.

While the story emerges from a very different time and place, the events of Acts 12 are also structured around boundaries and thresholds. Peter is angelically ushered out of his prison and through ‘the iron gate leading into the city’ (v.10), which opens miraculously before him. The maid Rhoda—a servant in the house to which Peter hastens—joyfully identifies him on his arrival at their threshold and proclaims his escape to the whole household.

The Buddhist tombs of north-western China encapsulate the borderland between living and dead, and between life and afterlife. In performing their imagined domestic duties, the women painted within these murals stand at the boundary between inside and outside space, and perhaps also between one world and another. They are the ones who are able to glimpse what is beyond the threshold.

Rhoda too has a privileged insight into what is on the other side of the door: Peter, who has himself moved from one condition to another; from the confines of his prison to a new liberty. She is the one who opens the gate for Peter, and she is the one who joyfully identifies him.

References

Qingquan, Li, and Fei Deng (Trans.). 2010. ‘Some Aspects of Time and Space as Seen in Liao-dynasty Tombs in Xuanhua’, Art in Translation 2.1: 29–54

Shen, Hsueh-Man. 2005. ‘Body Matters: Manikin Burials in the Liao Tombs of Xuanhua, Hebei Province’, Artibus Asiae 65.1: 99–141

Raphael

The Liberation of St Peter from Prison, from the Stanza di Eliodoro, 1514, Fresco, Width: 560 cm, Stanza di Eliodoro, Apostolic Palace, Vatican City; Scala / Art Resource, NY

Liberation and Light

Commentary by Rebecca Dean

This fresco was painted by Raphael in the early sixteenth century as part of a larger commission for the decoration of the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican. It uses three scenes to depict Peter’s miraculous escape from prison, split by the architecture of the room (the shuttered windows in the recess at the centre) and the architecture included within the painting itself. There is a certain chronology to these scenes, with the sleeping soldiers on the viewer’s left, the angel waking the slumbering Peter in the centre, and the angel and Peter making their escape on the right.

However, any straightforward scene-by-scene re-telling of the biblical story is complicated by the ways in which they intersect: already on the left-hand side, one soldier wakes another to point to the central scene, yet the soldiers on the right-hand side remain asleep as Peter approaches. This interplay contributes to the air of unreality that pervades the biblical account: is this really happening or is this just a dream?

It has been suggested that the face of Peter has a likeness to that of Pope Julius II (1443–1513), the man who commissioned Raphael’s work. The fresco has been seen to represent the hoped-for liberation of Italy from French control within the so-called Italian Wars. St Peter in Chains is a Feast Day in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions, and relics of these chains are held in the church of this same name in Rome.

One of the most frequently noted aspects of the painting is the use of light and shadow. The nocturnal setting for Raphael’s composition showcases the light of the moon, the soldier’s burning torch, the approaching dawn, the divine light of the angel, and the reflection of the light upon the soldiers’ armour. All of this is enriched by the natural light that floods through the windows below. The rich symbolism of light as divine presence and as hope is brought to life within this fresco.

References

Barolsky, Paul. 2015. ‘In the Light of Raphael’, Notes in the History of Art 34.2: 14–18

Hornik, Heidi. 2010. ‘Liberation from Tyranny’, Christian Reflections 35: 48–52

Asako Narahashi :

Kawaguchiko, from the series Half Awake and Half Asleep in Water, 2003 , Chromogenic print

Unknown Chinese artist :

Woman opening a phoenix-painted door, tomb of Zhang Shiqing, c.1093–1117 , Painted wood

Raphael :

The Liberation of St Peter from Prison, from the Stanza di Eliodoro, 1514 , Fresco

In Search of Reality

Comparative commentary by Rebecca Dean

This chapter of the Acts of the Apostles is full of the unexpected. It begins with the martyrdom of James the brother of John at the hands of Herod’s soldiers, and the subsequent arrest of Peter looks as though it may lead to a similar outcome. However, the Church is at work praying fervently to God, and something rather different unfolds whereby an angelic intervention sees Peter miraculously released from prison.

While this is certainly a story of God’s power at work, this power is by no means straightforwardly depicted. Peter mistakes the reality of the angel’s presence for a dream or vision of some kind, while the believers in Mary’s house mistake the reality of Peter’s presence for that of an angel. The suggestion that this is ‘Peter’s angel’ (Acts 12:15) indicates that the believers assume that he has died in prison and that his guardian angel has appeared to break this news to them. This offers a fascinating insight into some early Christian beliefs about different types of angels.

There are several moments of outright humour within the account, including the need for the angel to 'strike' (Greek: patassō) Peter on the side in order to get him to wake up, and Rhoda’s excited but accidental exclusion of the fugitive Peter from the house. The confusion of the prison escape continues in the later part of the chapter, which recalls the rather grisly and public demise of King Herod (vv.20–23). Technically, this refers to Herod Agrippa I, although the portrayal of this figure of Herod within Luke–Acts sometimes seems to amalgamate different Herods into one composite ‘tyrant’ (Dicken 2014; 2015). As he stands before the needy people of Tyre and Sidon, dressed in his royal robes, they erroneously proclaim that he is a god and not a mortal. Straightaway, another angel of the Lord again 'strikes' (patassō) the king, who is eaten by worms and (later) dies (v.23).

The mural from the tomb of Zhang Shiqing highlights the place of low-status servant women at the threshold between one place and another. In the Acts account, the servant-girl Rhoda (whose name is the Greek word for ‘Rose’) is mocked by the householders for what she reports to them. Humour at the expense of a ‘foolish’ slave was a common trope within ancient Graeco-Roman literature, yet here it is turned on its head, for it soon becomes apparent that Rhoda is not mistaken. In fact, she sees and proclaims the truth, reminding us of the promised outpouring of the Holy Spirit upon male and female slaves at the first Christian Pentecost (Acts 2). The God of the book of Acts makes Himself known to the lowly and to those who are often discounted as ‘fools’, inviting them to participate in His story.

The watery photograph of Mount Fuji presents a puzzling challenge to our sense of perspective. Where do we belong, and where should our focus lie? How do we, as fragile human beings, makes sense of the world in which we live? The events described in Acts 12 grapple with some of these same questions, portraying humanity at its worst and its best, and offering the perplexing reassurance of God’s presence in our midst.

The Raphael fresco captures much of the drama of the story of Peter’s miraculous escape from prison. The masterful use of light is only possible in the context of the shadows and darkness found elsewhere within the painting. In this way, the picture testifies to a concept of hope that is firmly grounded within the gritty realities of human existence, and yet somehow able to transcend these constraints.

References

Cobb, Christy. 2019. Slavery, Gender, Truth, and Power in Luke–Acts and Other Ancient Narratives (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan)

Dicken, Frank. 2014. Herod as a Composite Character in Luke-Acts (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck)

———. 2015. ‘Composite “Herod” in Luke-Acts’, www.bibleinterp.arizona.edu, [accessed 4 May 2021]

Gaventa, Beverly Roberts. 2003. The Acts of the Apostles, Abingdon New Testament Commentaries (Nashville: Abingdon Press)

Spencer, F. Scott. 1997. Acts (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press)

Commentaries by Rebecca Dean