John 16:16–24

Presence Beyond Absence

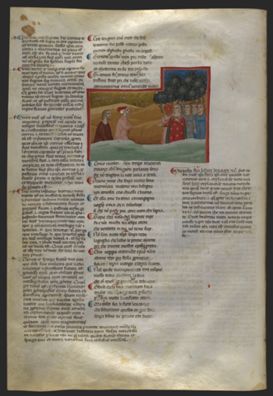

Duccio

Christ Taking Leave of His Disciples, from the Maestà, 1308–11, Tempera and gold on panel, 50 x 53 cm, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena; De Agostini Picture Library / G. Nimatallah / Bridgeman Images

Vital Conversations

Commentary by Vittorio Montemaggi

Duccio’s Maestà altarpiece—completed in 1311 and carried in procession from the artist’s workshop to its new home in Siena’s cathedral—intertwined civic and religious significance. It reminds us how art can generate community by precipitating shared reflection on vital questions.

Who are we? Why are we here? Where are we going? Such questions can be approached in a variety of ways, consciously and subconsciously: in joy, love, fear, doubt, anger, hope. However they are approached, they are a fundamental dimension of the conversations that constitute human cultures, their evolution and their transformations.

One such conversation is portrayed in this panel—one of the twenty-six panels depicting the Passion and Resurrection of Christ on the back of the Maestà. It is a conversation about homecoming and, according to Christian tradition, an integral part of the founding of the Church. As recounted in John 16:16–24, the conversation is caught in a tension between the presence and absence of Christ, and is meant to prepare Jesus’s disciples for suffering and death in recognition of a deeper, eternal entry into joy. The inclusion of an open door behind the seated figure of Christ in Duccio’s panel is striking, and its darkness seems deliberately to suggest both uncertainty and future possibility (Rosser 2012: 489–90).

The drama in this panel of the Maestà might not be as apparent as that of the panels surrounding it. All we seem to have is conversation. Yet, as in the Gospel of John, the drama of this conversation offers an interpretative key for reflecting on the events surrounding it. Here the disciples are called, personally and directly, to recognize in the master they have chosen to follow a truth that transcends the distinction between absence and presence—life and death—as we normally conceive of them. And they are called to realize that they too can consciously partake in the same truth. Duccio’s panel challenges us to recognize in Christ, in art, and in each other the transforming power of conversation: through darkness and into the possibility of light.

References

Rosser, Gervase. 2012. ‘Beyond Naturalism in Art and Poetry: Duccio and Dante on the Road to Emmaus’, Art History, 35.3: 474–497

Barnett Newman

Abraham, 1949, Oil on canvas, 210.2 x 87.7 cm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York; 651.1959, © Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Darkness and Nascent Light

Commentary by Vittorio Montemaggi

In recalling his painting of Abraham, the American abstract artist Barnett Newman (d. 1970) said that ‘The terror of it was intense’.

The process of artistic creation confronted Newman with radical inner exploration. The name of the work is both that of the biblical patriarch and of Newman’s father, who had died a couple of years earlier. The overwhelmingly dark tones of the painting could perhaps reflect Newman’s perception of a darkness in the life of both men.

In his oeuvre Newman engages with his Jewish roots, and some of his later work—notably Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachtani (1958–66)—also explicitly engages with notions of darkness and abandonment at the heart of the Christian story. There is no evidence of the latter in Abraham. Yet contemplation of this painting—in which a thick, black vertical ‘zip’ struggles to stand out against an only mildly lighter background—can generate fruitful insight into John 16:16–24.

What does it mean to ‘go back to the Father’? The disciples’ question is a question about life beyond death. Yet it has little spiritual purchase if it is not recognized, first of all, as an earthly question. Christ indicates that the journey to the Father is first a journey towards suffering and death, so it is understandable that the disciples are confused and afraid at the thought of what will become of them on their own journey to the Father.

Newman’s Abraham speaks of and to the terror of a journeying that is inextricably tied to suffering and death. But it also speaks of and to the potential for discovery such journeying entails.

If we look closely, we can discern amidst the various levels of darkness unexpected, nascent light. Are we encouraged by this light to discern life as well as death; even life through death? In such light, we might also recognize Abraham as a metaphor for artistic creation. The painting challenges us to face darkness in our own journeying. Whether or not we think of our journeying as being towards the Father, refusing to avoid darkness might bring us to nascent light.

Master of the Antiphonar of Padua

Statius with Dante and Beatrice with seven virtues, calling Dante, from Dante's Divina Commedia, c.1300–50, Tempera on vellum, 390 x 260 mm, The British Library, London; Egerton 943, fol. 124v, © The British Library Board

Whose Words?

Commentary by Vittorio Montemaggi

In one of the most striking and enigmatic passages of Dante Alighieri’s Divina Commedia (Purgatorio 33.1–15), Beatrice speaks as her own the words of John 16:16. We are in the Earthly Paradise, and Beatrice speaks these words to seven women who represent respectively the four cardinal virtues and the three theological virtues. They have just sung a psalm in lament at the corruption of the earthly Church, and we are told Beatrice responds to this, firstly, with a sorrow like Mary’s at the foot of the Cross, and secondly, with her utterance ‘a little while and you will see me no more...’.

These words are addressed also to Dante who, when Beatrice died, despaired, failing to recognize in death the possibility of eternal union with God. So as to grow in virtue, he now needs to recognize in Beatrice the truth offered by Christ to his disciples in John 16:16–24.

By speaking Christ’s words, Beatrice blurs easy distinctions between Christ and other human beings. Whose words are these? Christ’s? Beatrice’s? Both? And how does this relate to Dante, who as character is called to recognize in Beatrice’s words the truth of Christ, and who as author is the one speaking Christ’s words in and through Beatrice?

There is no easy distinction between the truth of Christ and that of particular human beings. Christians are called to virtue not just by following but by becoming Christ. His words are to become our words, our words are to become his words.

The Master of the Antiphonar of Padua’s illumination of Beatrice and the Virtues in a fourteenth-century manuscript of Dante’s Commedia offers a striking visual counterpart to this theological recognition. It illustrates the text of Purgatorio 33, articulating itself around the text, in visual dialogue not just with the text but also the surrounding commentary.

In both image and text, the manuscript thus visually presents itself as a Bible might have. Inspired by Scripture, Dante’s literary art generates visual art that invites us to recognize in Dante’s poetry—and thereby in human art more broadly—a potential significance comparable to that of Scripture itself.

Duccio :

Christ Taking Leave of His Disciples, from the Maestà, 1308–11 , Tempera and gold on panel

Barnett Newman :

Abraham, 1949 , Oil on canvas

Master of the Antiphonar of Padua :

Statius with Dante and Beatrice with seven virtues, calling Dante, from Dante's Divina Commedia, c.1300–50 , Tempera on vellum

Conversational Journeying

Comparative commentary by Vittorio Montemaggi

At the bottom of Duccio’s depiction of Christ taking leave of his disciples, the left, sandalled foot of one of the disciples, on the threshold of the painting itself, points beyond it. Perhaps it is intended to suggest that the conversation depicted in the panel wishes to move towards us. Indeed, if we look closely, we notice that the way Duccio depicts feet in this scene of the Maestà seems to reflect the significance of the work as a whole. Though a painting, the altarpiece is meant to be a living expression of the truths it depicts, and wants to draw us to partake in these truths.

Directly above this foot that sits on the threshold of the painting, we see the foot of another disciple, emerging from under his tunic. Both feet point in a similar direction, towards us. The significance of this gesture is enhanced if we note that the preceding scene in the Maestà is that of Jesus washing his disciples’ feet, which in turn follows that of the institution of the Eucharist (or Last Supper).

In the Gospel of John, the latter episode is absent, and the washing of the feet has a significance comparable to it. It is the moment in which Jesus leaves his disciples—and us—a tangible sign of his eternal presence. By pointing towards us, the disciples' feet remind us that the conversation in John 16:16–24 is predicated upon the concrete care that Jesus has for those with whom he is speaking.

Such care is personal and intimate. While pointing towards us, the foot emerging beneath the orange tunic points first of all to the feet of Christ himself, which in turn point to the disciple's foot that sits on the threshold of the painting. The visual interplay between the feet that are visible in this scene has Christ as focal point, but ultimately opens outwards, towards us.

Christ is the focal point of meaning, but that meaning faces outwards, towards the world as a whole, self-givingly. Christ's departure ultimately signals not his absence, but his presence in, through, and even as us. Whatever our journey, Christ tends to our feet. Our movements are grounded in his. He is the care by which we move, and our every step is concrete expression of such love.

In Purgatorio 33, Beatrice's speech is grounded in Christ's. He is the Word by which she speaks, and her words are no less her own because of this. It is in speaking like Christ that we are most truly ourselves; just as it is in realizing that Christ is the love by which we move that our steps are most truthfully taken. The same applies to the poet: his words are most truly and truthfully themselves if rooted in Christ's, in God's own Word.

In visually presenting Dante Alighieri's poem to us as the Bible might have been presented, the British Library's Egerton MS 943 thus reveals something essential about Dante's art. And in interweaving his art with Dante's, the Master of the Antiphonar of Padua actively partakes in this revealing, thereby also revealing his own art to be somewhat like the foot of the disciple on the threshold of Duccio's painting. It is a creative gesture which can consciously draw us into a conversation about the value of art—a conversation that can in turn be integrated into the broader conversation started by Christ in taking leave of his disciples.

Does such conversation about art need to be restricted to Christian art? Barnett Newman's Abraham suggests otherwise. Like the patriarch Abraham, the disciples are called in John 16 to be open to sacrificing what they hold most dear. And, like Newman, they are called to face inner and outer darkness to produce the best work they are capable of. In this sense, Newman's art and Christian discipleship bear structural similarities.

This is not to impose on either the other's identity. It is to recognize the possibility of a conversation between the two. The contours of this conversation will depend on the occasion for it. But the journey of this conversation will in any case involve transformation for present-day Christians who look at the art, and for the artwork itself. And consequently for us.

In such mutual transformation there lies a fruitful and mysterious open-endedness. It is an open-endedness implicit in the very process of commenting visually on Scripture. How will you take part in this journey?

Commentaries by Vittorio Montemaggi