Matthew 26:20–25; Mark 14:17–21; Luke 22:14, 21–24; John 13:21–30

The Apostle Judas

Duccio

The Last Supper, from the Maestà, 1308–11, Tempera and gold on panel, 50 x 53 cm, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena; Scala / Art Resource, NY

Condemnation or Salvation?

Commentary by Adrienne Dengerink Chaplin

Judas Iscariot is often portrayed as the personification of evil, a callous traitor, and a man beyond redemption. Yet, here, another possibility presents itself.

The Last Supper is one of a series of scenes from the Passion of Christ on the back of the Maestà, a large altarpiece made by Duccio di Buoninsegna for Siena Cathedral between 1308 and 1311. In the early eighteenth century the altarpiece was dismantled, and the back panels were separated. This one is now on display in Siena’s Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo.

In John’s Gospel, the disciple ‘whom Jesus loved’ (John 13:23) asks him who it is that is going to betray him, to which Jesus responds: ‘It is the one to whom I give this piece of bread’ (13:26 NRSV) . It may be that Duccio is drawing on this account, capturing Jesus in the act of handing a piece of bread to Judas, the son of Simon Iscariot (shown here in the foreground at left of centre).

But the panel can be read another way, not denying or erasing, but complementing and completing our first (Johannine) interpretation. The table is spread with Passover food and drink. In this way, Duccio reminds the viewer that Christ’s offer of bread to Judas takes place in the context of the Lord’s Supper, which does not feature in John’s narrative but is mentioned by the other gospel writers. Thus, the painting may show the moment at which Jesus breaks a loaf of bread and shares the pieces with his disciples as a sign of his broken body (Matthew 26:26–28; Mark 14:22–24; Luke 22:19–20).

By allowing the image to speak to both readings, Jesus’s outstretched hand, positioned as it is next to the Paschal lamb in the table’s centre, places Judas’s betrayal in a larger story of fall and redemption. Strikingly, Jesus’s identification of Judas as traitor comes with the simultaneous offer of ‘the forgiveness of sins’ (Matthew 26:28).

There may have been several human motives for Judas’s betrayal or ‘handing over’ (the Greek word paradidōmi can stand for either) of his master. Some argue it was greed; others, jealousy; yet others, frustration with Jesus’s refusal to deliver a political kingdom. Yet, whatever personal interests, moral failure, or political disillusionment may have played a role in Judas’s treacherous act, the act itself was, mysteriously, bewilderingly, part of a larger divine economy of salvation.

References

Bellosi, Luciano. 1999. Duccio: The Maesta (London: Thames & Hudson)

Deuchler, Florens. 1979. ‘Duccio Doctus: New Readings for the Maestà’, The Art Bulletin 61.4: 541–49

White, John. 1979. Duccio: Tuscan Art and the Mediaeval Workshop (London: Thames & Hudson)

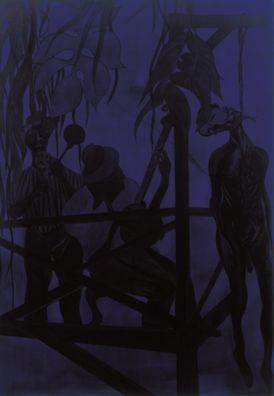

Chris Ofili

Iscariot Blues, 2006, Oil and charcoal on linen, 281 x 194.9 cm, Victoria Miro; © Chris Ofili, Courtesy Victoria Miro and David Zwirner

Slavery and Liberation

Commentary by Adrienne Dengerink Chaplin

Iscariot Blues is one of a series called The Blue Rider—a reference to the early twentieth-century German artists collective Der Blaue Reiter—painted by Chris Ofili shortly after his move from London to Trinidad in 2005. The dark hues of the paintings contrast starkly with the brightly coloured canvasses of his earlier period. In Iscariot Blues we can only just make out the outlines of a man hanging from a gallows alongside two musicians. The juxtaposition is strange and unsettling.

The title suggests that the man on the gallows represents Judas Iscariot, though the image may also make reference to Trinidad’s history of slavery. Referring to the Judas figure Ofili commented:

I was brought up to think that Judas was the bad guy … and that he was responsible for the persecution of the Son of God. In further readings, there’s an understanding that Judas knew that in order for man to be saved, Jesus would have to die. And the only way for that to happen would be if he was betrayed by those closest to him. So it was interesting that he could be transformed from this 'baddie' to a 'goodie' all of a sudden. (Nesbitt et al. 2010: 99)

Ofili’s reflections echo those of the Swiss theologian Karl Barth (1896–1968) when he described Judas as ‘the sinner without equal, who offered himself at the decisive moment to carry out the will of God, not in spite of his unparalleled sin, but in it’ (Barth 1957: 503). For Ofili, the contrast between the violent image of the hanging dead figure with the depiction of the blues musicians captured some of the tension in that ambiguity.

Jamaican-born British cultural critic Stuart Hall, drawing on the American novelist James Baldwin, once described the blues as combining in its cadences the cry of trouble and tribulation with the promise of the joy of jubilee: ‘It takes us to a dark place, but it never leaves us there’ (Hall 2018: 131).

Iscariot Blues can be interpreted as alluding to Judas’s role in the story of redemption, a story that goes back all the way to Israel’s liberation from slavery in Egypt. It invites reflection on the unfathomable part Judas played in that story, by juxtaposing this gruesome death with the soulful music played under open skies on a sweet evening in Trinidad.

References

Barth, Karl. 1957. Church Dogmatics Volume 2, Part 2, ed. by G. W. Bromiley and T. F. Torrance, trans. by G. W. Bromiley (Edinburgh: T & T Clark)

Hall, Stuart. 2018. Familiar Stranger: A Life between Two Islands (London: Penguin Books)

Nesbitt, Judith, Okwui Enwezor, Ekow Eshun and others. 2010. Chris Ofili (London: Tate Gallery Publications)

Chris Ofili

The Upper Room, 1999–2002, Oil paint, acrylic paint, glitter, graphite, pen, elephant dung, polyester resin and map pins on 13 canvases, Support, each: 1832 x 1228 mm support: 2442 x 1830 mm, Tate; Purchased with assistance from Tate Members, the Art Fund and private benefactors 2005, T11925, © Chris Ofili, Courtesy Victoria Miro and David Zwirner; Photo: © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Eucharistic Humility

Commentary by Adrienne Dengerink Chaplin

Wherever it has been installed, The Upper Room by Chris Ofili has been a space intended for quiet contemplation. As Ofili explained, he was ‘trying to create an atmosphere for people to feel somehow out of themselves’ (the EYE 2005).

Designed by Ofili in collaboration with the architect David Adjaye, the room is reached via an upwardly sloping, dimly-lit passageway, thus slowing the viewer down while creating a sense of suspense and anticipation (Nesbitt et al. 2010: 17–18).

Upon entering the rectangular, wood-panelled room visitors encounter thirteen canvasses, spot-lit from above. Six lean against each of the long side walls and one against the short wall at the far end. Each of the paintings is supported on two clumps of elephant dung, one of Ofili’s trademark materials. Each displays the outline of a long-tailed, waistcoated rhesus macaque monkey against a background of lush vegetation painted in different colours, reflected in the paintings’ Spanish titles: Mono (‘monkey’ with a word play on ‘monochrome) Gris, Mono Verde, Mono Rosso, and so on. Except for the one at the end, each monkey is painted in profile holding a chalice.

It has been suggested that the monkey figure was a reference to the Hindu epic, the Ramayana, in which the deity Hanuman leads an army of monkeys into a battle against evil (Enwezor in Nesbitt et al. 2010: 73). But Ofili, who was raised a Roman Catholic, is also interested in his own Christian heritage, as is clear from the title of the work. And in Christian iconography, monkeys or apes can sometimes stand for evil, or specifically for Satan (Ferguson 1961: 11). Moreover, in Byzantine icons demonic figures are often depicted in profile as they do not have both eyes on God (Uspenski 1976: 73 n.4; Williams 2009: 53).

We are told in John’s Gospel that when Christ identified Judas as his betrayer, Satan entered him (John 13:27). Yet, in Ofili’s installation, Judas is not demonized as the evil ‘other’. Instead, the work represents all twelve disciples in the same way and may therefore remind us of the fact that all twelve betrayed and deserted Jesus that same evening. (Matthew 26:56; Mark 14: 50–52).

The Upper Room may invite us to ponder the mystery of the eucharistic feast where all believers come to the Lord’s table as Judas did—sinners in need of redemption by the sacrifice made once for all.

References

Ferguson, George. 1961. Signs and Symbols in Christian Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Nesbitt, Judith, Okwui Enwezor, Ekow Eshun and others. 2010. Chris Ofili (London: Tate Gallery Publications)

theEYE. 2005. Chris Ofili, The Upper Room https://vimeo.com/ondemand/theeyechrisofili

Uspenski, Boris. 1976. The Semiotics of the Russian Icon (Lisse: The Peter de Ridder Press)

Williams, Rowan. 2009. Dostoevsky: Language, Faith and Fiction (London: Continuum)

Duccio :

The Last Supper, from the Maestà, 1308–11 , Tempera and gold on panel

Chris Ofili :

Iscariot Blues, 2006 , Oil and charcoal on linen

Chris Ofili :

The Upper Room, 1999–2002 , Oil paint, acrylic paint, glitter, graphite, pen, elephant dung, polyester resin and map pins on 13 canvases

Scapegoat and Sacrificial Lamb

Comparative commentary by Adrienne Dengerink Chaplin

Every community seeks its scapegoats. They deflect attention from their own misdeeds and unite the tribe against a common foe. Throughout the history of Christianity, Judas has been conveniently cast in the role of heartless traitor. It puts all members of the faith community in a better light.

This attitude to Judas is reflected in the history of Western art. Depictions of the Last Supper typically show Judas with a malevolent expression, without a halo, as an outcast at the far end of the table or about to leave to do his evil deed.

The three works in this exhibition deviate from this tradition and do not single Judas out or demonize him as ‘the other’. In Chris Ofili’s The Upper Room the shapes of all the disciples are identical, each carrying a ‘chalice’ and each turned to the figure who occupies the position of Christ at the end. According to the gospel writers, all twelve disciples betrayed Jesus’s trust that evening in one way or another: some fell asleep while meant to watch (Matthew 26:40); others deserted him at his arrest (Matthew 26:56); yet others disowned him when he was interrogated (Matthew 26:70, 72, 74). Moreover, all this was foretold by Jesus with reference to the Jewish Scriptures (Psalm 41:9; Zechariah 11:12; 13:7; Matthew 26:34).

When the Gospel writers describe how Jesus identified ‘the one’ after his shocking announcement that someone would betray him that night, they each use slightly different wording. According to Matthew, Jesus referred to his betrayer in the past tense: ‘the one who has dipped his hand into the bowl with me’ (Matthew 26:23 NRSV). Mark recalls Jesus using the present tense: the ‘one who is dipping bread into the bowl with me’ (Mark 14:20). And John records him using a future tense: ‘the one to whom I give this piece of bread when I have dipped it in the dish’ (John 13:26 NRSV).

All these descriptions, however, could in principle have applied to all the disciples. Considering the Eastern custom of dipping pieces of bread or meat in a shared bowl of stew—or bitter spices at Passover—most of the disciples would, at some point during the evening, have dipped their bread in the same bowl as Jesus. But the narratives all testify to the incriminating fact that the betrayer shared a meal with the betrayed, a sign of deep friendship and intimacy, which would have been considered the ultimate breach of trust. It echoes David’s cry in one of his psalms: ‘Even my bosom friend in whom I trusted, who ate of my bread, has lifted the heel against me’ (Psalm 41:9).

The two works by Ofili in this exhibition prompt us to take another look at Duccio di Buoninsegna’s panel painting. The double reading of this work both as the moment where Jesus offers Judas a piece of bread to identify him as his betrayer and as the moment where he offers a piece to him as a token of his broken body for the forgiveness of sins, reminds us of the words of Jesus spoken at another dinner party, one hosted by Levi the tax collector: ‘I have come to call not the righteous but sinners to repentance’ (Luke 5:32 NRSV).

Of all the disciples Judas was the first openly to repent and the only one who, overcome by remorse, could no longer face going on living. Perhaps he remembered Jesus’s earlier words, perhaps spoken out of compassion rather than judgement: ‘woe to that one by whom the Son of Man is betrayed!’ (Mark 14:21 NRSV).

Since Ambrose (340–397 CE) and Augustine (354–430 CE) there has been a tradition that refers to Adam’s fall as felix culpa—a happy fault. The idea that Adam’s sin was fortunate because it brought salvation for humanity is also referred to in the Exsultet, the Paschal proclamation sung during the Easter Vigil: ‘O Happy Fault that merited such and so great a Redeemer!’ The same sentiment can be found in Howard Nemerov’s poem, The Historical Judas, which refers to Judas as ‘this most distinguished of our fellow sinners, who sponsored our redemption with his sin’ (Nemerov 1980:74).

Might we perhaps entertain the possibility that Judas’s treachery, too, was in some ways ‘a happy fault’?

The Upper Room and Iscariot Blues allude to the profound mystery of Judas’s role in the divine drama of salvation. They enable us to see the person of Judas both as sinner and as saint, both as victim and as God’s means of salvation. On such a reading, Judas and Jesus are bonded together in a shared redemption story in which each fulfils a double role, both a scapegoat and a sacrificial lamb.

References

Cane, Anthony. 2017. The Place of Judas Iscariot in Christology (Abingdon: Routledge)

Gubar, Susan. 2009. Judas: A Biography (New York: Norton & Company)

Nemerov, Howard. 1980. The Historical Judas, poem in Howard Nemerov’s Sentences (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press)

Commentaries by Adrienne Dengerink Chaplin