Joshua 2:1–24; 6:22–25

Rahab of Jericho

Khaled Jarrar

Whole in the Wall, 2014, Multimedia installation: sculptures (including pieces formed from reconstituted fragments of Apartheid Wall); video; photography; ©️ Khaled Jarrar; Photo ©️ Susan Hakuba

Breaking Border Barriers

Commentary by Devon Abts

A Palestinian artist who lives and works in the occupied West Bank, Khaled Jarrar is known for his provocative interventions at and around contemporary border walls. For his 2014 Whole in the Wall exhibit, Jarrar took a hammer to the Israeli-Palestinian ‘security fence,’ removing fragments of concrete which he later reconstituted as a set of sculptures expressing hope for unity in modern contexts of colonial violence.

Jarrar’s London installation of the project featured a giant concrete barrier running through the middle of the gallery: an unsightly grey mass confronting viewers with the suffocating physical and psychological effects of walling. The barrier was constructed to severely restrict access to parts of the exhibit, forcing gallery-goers to climb ungracefully through a small, Palestine-shaped hole in order to view the entire installation. In this way, Whole in the Wall confronts visitors with the dehumanizing effects of border barriers. At the same time, by breaking these structures down and giving them a new, creative purpose, his work invites the viewer to imagine a different reality: one which is expansive enough to resist the ‘insider–outsider’ dynamic of wall-building.

The Bible’s authors laboured carefully to construct walls around Rahab of Jericho, the infamous Canaanite sex-worker-turned-proselyte whose story is recorded in the book of Joshua (chapters 2 and 6). Prior to the invasion, she runs a brothel from the city’s ramparts—literally ‘on the outer side of the city wall’ (Joshua 2:15). Yet on a deeper level, this promiscuous foreign woman poses a genuine threat to Israel’s holy-war agenda (Sharp 2008: 98–99). Rahab must be contained. Thus, although she and her family escape the herem (Hebrew, ‘utter destruction’), they are ultimately resettled ‘outside the camp of Israel’ (Joshua 6:23) as ‘resident gentiles’ (Baskin 1979: 142).

Nevertheless, this unruly outsider refuses to be hemmed in. When she confesses faith in Israel’s God, Rahab speaks not as the Canaanite other, but ‘as an Israelite theologian’ (Gillmayr-Bucher 2007: 147). The paradigmatic outsider becomes an insider—and in so doing, she transgresses every boundary which is intended to keep her at a safe distance. Like Jarrar’s monumental sculptures, this larger-than-life biblical figure summons us to transcend the barriers of our imaginations and seek connection across the walls that divide.

References

Baskin, Judith. 1979. ‘The Rabbinic Transformations of Rahab the Harlot’, Notre Dame English Journal 11.2: 141–57

Gillmayr-Bucher, Susan. 2007. ‘“She Came to Test Him with Hard Questions”: Foreign Women and Their View on Israel’, Biblical Interpretation, 15.2: 135–50

Jarrar, Khaled. 2013. Whole in the Wall: The Exhibition Catalogue (London: Ayyam Gallery)

Sharp, Carolyn. 2008. Irony and Meaning in the Hebrew Bible (Bloomington: Indiana University Press)

Njideka Akunyili

Dwell: Aso Ebi, 2017, Acrylic, transfers, coloured pencil, collage, and commemorative fabric on paper, 243.84 x 314.96 cm, The Baltimore Museum of Art; Purchased as the gift of Nancy L. Dorman and Stanley Mazaroff, Baltimore, in Honor of Kristen Hileman, BMA 2018.79, Photography by Brian Forrest, courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art

The Outsider Woman’s Burden

Commentary by Devon Abts

Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s artworks invite viewers into deeply personal interior spaces, conveying her experience of cultural collision in the formation of a hybrid identity.

Dwell: Aso Ebi draws us into a space resembling the Nigerian home of the artist’s youth. On the wall hangs a portrait of her parents on their wedding day, and below, a smaller picture of her and her husband. Commemorative portrait fabric adorns the wall, evoking threads of intergenerational kinship. The floor is surreally decorated with transferred photographs taken from family albums and Nigerian magazines—a personal and cultural bedrock sustaining her experience as a Nigerian-American artist.

Akunyili Crosby depicts herself in a brightly coloured modern dress with her back turned to the viewer, looking over her right shoulder at her shoe. Her hand rests casually on a table beside a green and white teacup and a traditional Nigerian teapot painted in crisp black and yellow stripes. She appears unaware of the presence of any audience. At the same time, Akunyili Crosby’s work implicitly asks the viewer to consider what we do with our inherited traditions.

Like the artist, the biblical figure of Rahab negotiates a hybrid identity. A foreign woman and sex worker, this alluring outsider poses ‘the ultimate risk’ (Sharp 2008: 98) to the Israelites’ mission. Yet her confession of faith (Joshua 2:9–11) demonstrates insider knowledge of God’s salvation history; and in helping the Hebrew spies, she earns a place within that history (Gillmayr-Bucher 2007: 145). For centuries, then, Jewish and Christian readers have lauded Rahab as a heroic outsider-turned-proselyte who renounces her wayward ways and forges a new life among the Hebrews and their capacious God.

However, recent scholarly wisdom suggests that the narrative can be read from another angle, with Rahab as ‘the paradigmatic victim of violent colonization’ (Sharp 2012: 623). According to the postcolonial view, she willingly conspires with Israel against her own people. In return, Rahab and her family are relegated to a liminal position ‘outside the camp of Israel’ (Joshua 6:23).

Rahab’s name in Hebrew means ‘broad’—a reminder that she, like the creator of this artwork, cannot be understood apart from her hybridity. Seeing Rahab clearly requires holding our inherited traditions of biblical interpretation in tension with contemporary critical voices. How might we, as readers of Scripture, follow Akunyili Crosby’s example in creating a hospitable space broad enough to encompass the many dimensions of this fascinating biblical character?

References

Gillmayr-Bucher, Susan. 2007. ‘“She Came to Test Him with Hard Questions”: Foreign Women and Their View on Israel’, Biblical Interpretation, 15.2: 135–50

Sharp, Carolyn. 2008. Irony and Meaning in the Hebrew Bible (Bloomington: Indiana University Press)

______. 2012. ‘“Are You For Us, or For Our Adversaries?”: A Feminist and Postcolonial Interrogation of Joshua 2–12 for the Contemporary Church’, Interpretation 66.2: 141–52

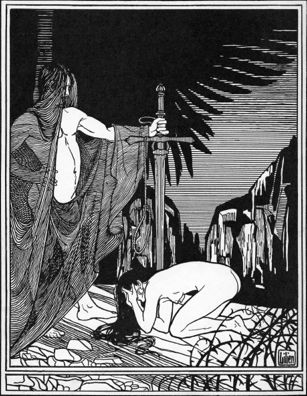

Ephraim Mose Lilien

Rahab, Die Jerichonitin, c.1900, Etching; Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo

Can You Spot the Hero?

Commentary by Devon Abts

Rahab, Die Jerichonitin (Rahab, of Jericho) is one of several engravings created by created by Ephraim Mose Lilien (1874–1925), a Jewish artist born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to accompany a series of Jewish-themed ballads composed by his friend, Börries von Münchhausen. Like their poetic source material, these illustrations celebrate ‘the epic-heroic qualities of the ancient Hebrews, their courage, strength, and natural beauty’ (Gossman 2004: 49) through fresh interpretations of the Jewish Scriptures.

The poem which inspired this engraving is loosely based on the biblical account of Rahab, the enigmatic zonah (Hebrew, usually translated ‘prostitute’) of Jericho who helps the Israelite spies escape in exchange for her family’s safety. Importantly, Münchhausen’s poem reimagines a key detail: the crimson cord—a symbol of deliverance in the book of Joshua (2:18)—becomes a noose on which Rahab hangs for betraying her people.

This cord occupies a central position in Lilien’s illustration. Poised above Rahab’s head, it takes on new meaning as an omen of judgment and retribution. At the same time, the artist adds his own interpretation by rendering the biblical heroine as the ideal of female obeisance and the object of male sexual conquest.

Lilien depicts Rahab as a beautiful young woman lying prostrate before a dominant male figure holding an enormous sword. Its tip seems to rest on the ground behind her, yet the blade intersects visually with her naked body, underscoring a threat of violence. Rahab hides her face in her hands, and her long, dark hair drapes over the crown of her head toward the rubble of Jericho. There is a strong evocation of sexual domination as the nearly nude male figure gazes downward upon the subjugated woman. He is the embodiment of a revitalized Jewish nation: beautiful, strong, dignified, free. One might even discern a hint of celestial authority. While most likely a palm tree, the large feather-like mass overshadowing the scene might also suggest a pair of angel’s wings.

Throughout history, Jewish and Christian readers have lauded Rahab as an unlikely Gentile heroine and faithful convert whose courage is justly rewarded. Münchhausen’s poem provided Lilien with a different interpretive lens—one which reinscribes the violence of the biblical narrative even as it defies the violence of prevailing anti-Semitic visual tropes. The result is an artwork that asks us to sit with Scripture even to the point of discomfort.

References

Gossman, Lionel. 2004. ‘Jugendstil in Firestone: The Jewish Illustrator E.M. Lilien (1874–1925)’, The Princeton University Library Chronicle, 66: 11–76

Sharp, Carolyn. 2004. ‘The Formation of Godly Community: Old Testament Hermeneutics in the Presence of the Other’, Anglican Theological Review, 86: 623–36

Khaled Jarrar :

Whole in the Wall, 2014 , Multimedia installation: sculptures (including pieces formed from reconstituted fragments of Apartheid Wall); video; photography

Njideka Akunyili :

Dwell: Aso Ebi, 2017 , Acrylic, transfers, coloured pencil, collage, and commemorative fabric on paper

Ephraim Mose Lilien :

Rahab, Die Jerichonitin, c.1900 , Etching

Reconnoitring Rahab

Comparative commentary by Devon Abts

The story of Rahab is recorded in Joshua 2:1–21 and 6:17, 22–25. During a reconnaissance mission to Jericho, two Israelite spies enter the house of Rahab (2:1), a sex worker who lives at the outermost edge of the Canaanite city (v15). She welcomes the spies into her home (v.2), confesses faith in their God (vv.9–11), and secures her family’s protection in exchange for helping them escape (vv.12–14). After the siege of Jericho, Rahab and her family are brought safely from the ruined city and placed ‘outside the camp of Israel’ (6:23). The author of Joshua adds that her family remains in Israel to this day, ‘for she hid the messengers whom Joshua sent to spy out Jericho’ (v.25).

A Gentile woman by birth and plucky brothel-keeper by profession, Rahab is the unlikeliest of biblical heroines. Yet the drama of her story has captivated the imagination of Jewish and Christian readers alike. According to rabbinic tradition, she married Joshua and became a progenitor of a prominent line of Hebrew prophets, including Jeremiah (Baskin 1979: 146). She earns a place in Matthew’s genealogy of Jesus (1:5), and the New Testament authors credit her as an exemplar of both faith (Hebrews 11:31) and works (James 2:25). Building on this scriptural tradition, the Church Fathers praise Rahab’s courage in showing hospitality towards the Jews and faith in their God (e.g., Clement of Alexandria, 1 Clement 12; Augustine, Contra Mendacium). For centuries, her story has been read as illustrative of ‘the marvellous purposes of God in working through unexpected agents to bring his plan of salvation to fruition’ (Sharp 2004: 630).

Significantly, however, this biblical narrative also has a darker, more sinister side. Viewed through a postcolonial lens Rahab appears, not as a heroic Gentile convert, but as a willing participant in the genocide of her own people (Sharp 2004: 631–33). Under threat of foreign invasion, she willingly colludes with the conquerors; and in return, she and her family are permanently placed ‘outside the camp of Israel’ (Joshua 6:23).

Such contemporary perspectives can make familiar discourses seem strange—and in so doing, these postcolonial readings allow us to see the story of Rahab with fresh eyes. In the same way, each of the three artworks in this exhibition invites us to read the biblical text in a new light.

Created at the dawn of the modern Zionist movement, Ephraim Moses Lilien’s engraving is part of a series of illustrations the artist made to accompany a set of poems composed by his friend and creative collaborator, Börries von Münchhausen. The organic, energetic forms of Jugendstil (German Art Nouveau) offered Lilien an ideal visual language to express his longing for the renewal of an authentically modern Jewish culture. It is unlikely that a cultural Zionist such as Lilien intended this artwork as a piece of political propaganda. However, when viewed through a postcolonial lens, his depiction of Rahab raises some disturbing questions about her fate in the biblical text. What is the cost of her willing submission to the invading powers?

At first glance, Khaled Jarrar’s enormous concrete sculptures may not seem to offer any substantial commentary on Rahab’s story. Yet if we read her narrative with this work in mind, several parallels begin to emerge. Like Jarrar, the biblical figure of Rahab defies the colonial logic of walling. Her brothel—built into the very walls of Jericho (2:15)—is a haven of hospitality for strangers and outsiders. In welcoming the Israelite spies and professing faith in their God, she ‘successfully moves the border between herself and the spies, between self and other’ (Gillmayr-Bucher 2007: 145). Each time he takes a hammer to the separation wall, Jarrar undermines the barriers that separate families, friends, and neighbours. In repurposing the wall, the artist invites his viewers to transcend the psychological barriers of their colonized imaginations and to recognize humanity’s essential interdependence. Perhaps this, too, is a part of Rahab’s legacy.

If Lilien’s artwork illuminates Rahab’s violent domestication, and Jarrar elucidates a Rahab who refuses to be domesticated, what insights might we glean from the tranquil domesticity of Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s self-portrait?

Like Jarrar’s sculptures, this painting was not conceived as a response to the biblical text. However, in offering a constructive vision of her own hybridity, Akunyili Crosby invites us to consider how identities take shape under circumstances of cultural collision. Moreover, the hospitality of her work invites the modern reader of the Bible to consider how she might foster a hospitable discourse around Rahab. Like so many favourite biblical figures, Rahab asks to be considered from multiple angles. How might we, as interpreters of Scripture, enter into dialogue with those who see her from a different perspective?

References

Dube, Musa. 2000. Postcolonial Feminist Interpretation of the Bible (Danvers: Chalice Press)

Gossman, Lionel. 2004. ‘Jugendstil in Firestone: The Jewish Illustrator E.M. Lilien (1874–1925)’, The Princeton University Library Chronicle, 66: 11–76

Pui-Lan, Kwok. 2006. ‘Sexual Morality and National Politics: Reading Biblical “Loose Women”’, in Engaging the Bible: Critical Readings from Contemporary Women, ed. by Choi Hee An and Katheryn Pfisterer Darrby (Minneapolis: Fortress Press)

Gillmayr-Bucher, Susan. 2007. ‘“She Came to Test Him with Hard Questions”: Foreign Women and Their View on Israel’, Biblical Interpretation, 15.2: 135–50

Sharp, Carolyn. 2008. Irony and Meaning in the Hebrew Bible (Bloomington: Indiana University Press)

______. 2012. ‘“Are You For Us, or For Our Adversaries?”: A Feminist and Postcolonial Interrogation of Joshua 2–12 for the Contemporary Church’, Interpretation 66.2: 141–52

Commentaries by Devon Abts