Joshua 10

The Longest Day

Unknown French artist [Paris]

The Longest Day; Israel's Enemies Humiliated, from The Crusader Bible (The Morgan Picture Bible), c.1244–54, Illumination on vellum, 390 x 300 mm, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; MS M.638, fol. 11r, Photo: Courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum

A Mirror for Princes

Commentary by Rowena Loverance

One can almost hear the pounding hooves and the clash of weapons emanating from the pages of the Morgan Crusader Bible.

In the centre of the top register of this two-tiered image is Joshua, astride a bay horse caparisoned in white; blood spurts from the end of his lance as his victim topples backwards from his horse. As the Crusader poet Bertran de Born exulted:

Trumpets, drums, standards and pennons and ensigns and horses white and black we soon shall see, and the world will be good. (Paden 1986: 398)

Outlined against the royal blue sky and with raised arm, Joshua appears a second time in the top tier, commanding the sun and moon (Joshua 10:12–13), which are both depicted in the heavens at the upper right of the composition. At the right of the lower register, he is shown a third time, in this instance standing without his helm and holding a lance, as he exhorts the Israelite captains to place their feet on the necks of the Amorite kings (10:24), reminding them that it is God who has given them the victory (10:25).

The Morgan Crusader Bible has long been thought to have been produced in Paris at the court of Louis IX in the mid-1240s, around the time he was planning the Sixth Crusade. Joshua had been regularly invoked since the start of the Crusades and Louis IX may have made a personal connection: when he commissioned the Old Testament windows of the Sainte-Chapelle (1238–48), the Joshua cycle was placed directly behind Louis’s own place in the chapel.

The forty-six folios of the Crusader Bible were painted without text; this, and its comparatively large size, suggest it was intended to offer the reader a visually immersive experience. The multiple captions seen today were added at intervals in five languages over the next four hundred years: Latin, Persian, Arabic, Judaeo-Persian, and Hebrew.

Louis’s crusade in 1250 proved a failure, but the story of Joshua still served him as a model to institute domestic reforms, designed to set him and his kingdom right with God.

References

Gaposchkin, M. C. 2008. ‘Louis IX, Crusade and the Promise of Joshua in the Holy Land’, Journal of Medieval History, 34.3: 245–74

Paden, William Doremus, Tilde Sankovitch, and Patricia H. Stäblein (eds.). 1986. The Poems of the Troubadour Bertran de Born (Berkeley: University of California Press)

Unknown Western Roman Empire artist

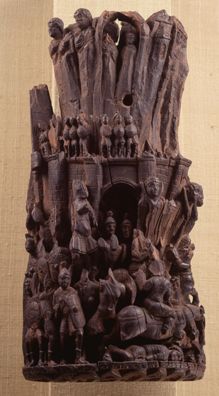

Liberation of a Beleaguered City, c.400, Boxwood carving, 45.5 x 22.5 x 10.3 cm, Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst der Staatliche Museen, Berlin; Inv. 4782, bpk Bildagentur / Staatliche Museen, Berlin / Jürgen Liepe / Art Resource, NY

Be Strong and of Good Courage

Commentary by Rowena Loverance

So rare is this high-relief wooden sculpture that it is impossible to be at all certain either of its provenance or original purpose. It was said at the time of its acquisition in 1900 to be from Egypt, but is associated with late-Roman Ravenna in current scholarship. It may have been part of a tiered series of narrative scenes, from which the other tiers are now missing. It is usually dated on stylistic grounds to the early fifth century (Von Törne 2010).

Joseph Strzygowski (1862–1941), who purchased the object for the new Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin, was the first to note parallels for the figures visible here hanging on forked staves. They recall scenes of the execution of the Amorite kings (Joshua 10:26) that can be found on the Vatican Joshua Roll. Since then, although other possible historical interpretations of the scene have been suggested, a biblical interpretation remains the most likely.

Reading around the sculpture’s curved surface, we can follow the arrival on foot of the Israelites after their forced march. Joshua is perhaps the damaged figure in the middle register. The Gibeonites sallying forth to help him are also shown, as is the flight of the Amorites on horseback and the execution of their kings (just four, rather than the five mentioned in the text). More soldiers, shown small scale, man the walls, two taller figures stand sheltered within a city gate, and three monumental bearded figures loom protectively outside the walls.

These protective figures have been read as Christian saints, and there are certainly Christian references elsewhere on the relief—the leading foot-soldier carries a labarum, the standard popularized in the early fourth century by the Emperor Constantine. Origen, in his Homilies on Joshua, assimilates Joshua with Jesus, and presents the battle for Canaan as a spiritual struggle, the internal battle against the principalities and powers that incite to sin (Homilies 1.6). Presiding over but disengaged from the carnage below, the protective figures radiate a feeling of security and endurance, of confidence in the eventual outcome of the struggle. This is surely the core message of Joshua 10: ‘Do not be afraid or dismayed; be strong, and of good courage’ (10:25).

References

Origen. 2002. Homilies on Joshua, The Fathers of the Church, vol. 105, trans. by Barbara J. Bruce (Washington, D.C: The Catholic University of America Press, 2002)

Von Törne, Anna E. 2010. Stadtbelagerung in der Spätantike—das Berliner Holzrelief (Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag)

Unknown Byzantine artist

Scenes from Joshua 10, from the Joshua Roll, c.950, Tempera and gold on vellum, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City; Vat. Pal. graec. 431, sheet XIIIr, By permission of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, with all rights reserved

On a Roll

Commentary by Rowena Loverance

We are not viewing this tenth-century luxury object as its commissioner would have done: the sheets would have been glued together to form a roll slightly more than 10.5 metres long. This explains why this sheet may seem unlocalized—the town of Gibeon, a seated female figure personifying the town, and the sun standing still overhead all appear at the end of the previous sheet. On this sheet we see Joshua speaking to the Lord (Joshua 10:12), the battle beneath God’s cloud of hailstones (10:11), and the report to Joshua of the finding of the five kings (10:16). On the next sheet the five kings hang from their forked staves.

These images must have struck a chord with the wider public, for they were widely copied in subsequent centuries, in illustrated Octateuch manuscripts, and on ivories.

The Byzantines were practised at typology, so they mined the book of Joshua, the sixth book of the Octateuch, for a variety of models. They saw themselves as an elect nation, the new Israel, so would have taken pride in scenes of God raining down destruction on Israel’s enemies (Eshel 2018: 106). Joshua’s role in leading the Israelites into Canaan made him a role model for military leaders campaigning to recover the Holy Land from the Arabs. The parakoimomenos (keeper of the king's bedchamber) Basil, a well-known art patron, and emperors Nicephorus Phocas and John Tzimisces, all of whom campaigned in Syria and Palestine, have been put forward at various times as possible patrons of the Roll.

Joshua belongs to the pre-kingly period of Israel, yet the Roll depicts him enthroned, haloed like a Byzantine emperor and with his feet on a suppedaneum (foot rest), surrounded by his soldiers, as he prepares to pass judgement on the defeated Amorite kings. Here it is clearly the righteous ruler who is being invoked.

The current flattened state of the Roll limits our understanding of the sense of motion it must have originally conveyed, as Joshua’s divinely-inspired victories rolled inexorably on, like those of the Roman emperors related on the triumphal columns which were still standing in Constantinople when the Roll was made.

References

Eshel, Shay. 2018. The Concept of the Elect Nation in Byzantium (Leiden: Brill)

Wander, Steven H. 2012. The Joshua Roll (Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag)

Unknown French artist [Paris] :

The Longest Day; Israel's Enemies Humiliated, from The Crusader Bible (The Morgan Picture Bible), c.1244–54 , Illumination on vellum

Unknown Western Roman Empire artist :

Liberation of a Beleaguered City, c.400 , Boxwood carving

Unknown Byzantine artist :

Scenes from Joshua 10, from the Joshua Roll, c.950 , Tempera and gold on vellum

Emergency Stop

Comparative commentary by Rowena Loverance

Earth stopped. The Holy City hit a mountain

As a tray of dishes meets a swinging door

(X. J. Kennedy, ‘Joshua’)

If the sun and moon were to stop moving for a day, what chaos would be caused? Could the earth survive?

Only in the last two generations has humanity had the power to destroy its own planet. With this new sensitivity to humanity’s capacity to cause global disaster, we are bound today to read Joshua’s command to the sun and moon to stop in their courses (Joshua 10:12–14) in a very different way from previous generations. That he does so to enable him to complete his military relief of the Canaanite town of Gibeon, and the defeat of the besieging Amorites, could appear to us to be a gravely insufficient justification.

The stopping of the spheres may simply be a literary trope, of course. This literary line of thought is strengthened by the reference in Joshua 10:13 to ‘the Book of Jashar’—a lost book, mentioned only twice in the Hebrew Bible (cf. 2 Samuel 1:18), perhaps containing battle hymns. What is more, there are other such cosmic allusions embedded in the narratives of the Bible. Rather than Joshua 10’s continued sunlight, Exodus 10 describes three days of darkness as one of the plagues inflicted upon Egypt before the Exodus, and in the book of Judges the Song of Deborah tells of how the stars in their courses fought against Sisera (Judges 5:20).

Perhaps the extraordinary events of Joshua 10 may refer to an actual eclipse. This hypothesis was first proposed in 1918, but only very recently has science been able accurately to test it. Based on their recent research, two Cambridge physicists have argued that the events of Joshua 10 took place on 30 October 1207 BCE, in the afternoon: the oldest solar eclipse ever recorded (Humphreys and Waddington 2017).

But the real issue posed for modern readers by the text may not so much be this sun-stopping, science-stretching event, as the genocidal destruction apparently commanded by God (Joshua 10:40). There is now widespread scholarly agreement that, although the text recounts events of c.1200 BCE, it forms part of the work of the Deuteronomist historian(s), receiving its final editing in the exilic period in the mid-sixth century BCE. Some contemporary writers (Collins 2005: 62) have commented on the irony of the fact that in this text the Hebrews apparently show no misgivings in doing to others what they themselves have just suffered.

Recent instances of genocide have brought home the urgent need to come to some accommodation with these herem (total destruction) texts, which are connected with ideas about the importance of radically ‘purifying’ a land. But one should not jump to the conclusion that readers of these texts through history have always had such ideas as their principal focus. The three artworks chosen here—from three different medieval contexts—reveal a more complex picture.

The original provenance of the remarkable and rare carved wood relief, now in Berlin, is not known, but it seems to date from the fifth century, a time when Joshua was being cited as a prefiguration of Christ by both Eastern and Western writers.

By the mid-tenth century, when the Joshua Roll was created in Constantinople, the use by Byzantine emperors of Old Testament warrior prototypes (such as Joshua) as exemplars is well-attested, as they sought to wrest control of Syria and Palestine from rival Islamic caliphates. Western crusaders made these links too, as evidenced by the folios dedicated to the Joshua story in the Morgan Crusader Bible (10r–11v)—not to mention episodes such as their solemn circumambulation around the walls of Jerusalem in 1099, before its bloodthirsty sack, which self-consciously replicated the sack of Jericho in Joshua 6.

All three works are unflinchingly honest in their use of graphic images of warfare. But they vary in the role they give to the cosmic intervention in the battle. The Berlin relief does not refer to it at all; the Joshua Roll reverses the biblical order of events and makes the hailstones the culmination of God’s intervention. Only the Morgan Bible gives centre stage to Joshua’s hubristic command to the sun and moon to stand still.

At a time when human hubris could have cosmic consequences, it seems that both theologians and artists have yet fully to explore the significance of the Deuteronomist writer’s unique event: ‘when the Lord hearkened to the voice of a human being’ (10:14) and made the movement of the spheres serve the outcome of a military campaign.

References

Collins, John J. 2005. The Bible After Babel: Historical Criticism in a Postmodern Age (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Company)

Hofreiter, Christian. 2018. Making Sense of Old Testament Genocide: Christian Interpretations of Herem Passages (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Humphreys, Colin, and Graeme Waddington. 2017. ‘Solar Eclipse of 1207 BC Helps to Date Pharaohs’, Astronomy & Geophysics, 58.5: 5.39–5.42

Kennedy, X. J. ‘Joshua’. In a Prominent Bar in Secaucus: New and Selected Poems, 1955–2007, p. 89. © 2007 X. J. Kennedy. Reused with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press

![The Longest Day; Israel's Enemies Humiliated, from The Crusader Bible (The Morgan Picture Bible), MS M.638, fol. 11r. by Unknown French Artist [Paris]](https://images-live.thevcs.org/iiif/2/AW0222_cropped_coloured.ptif/full/!400,396/0/default.jpg)

Commentaries by Rowena Loverance