Joshua 6

The Battle of Jericho

Giovanni di Paolo

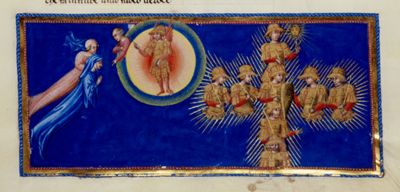

Miniature of Dante and Beatrice ascending to the Heaven of Mars, from Dante Alighieri Divina Commedia, Paradiso XVIII, c.1450, Illumination on parchment, 365 x 258 mm (page), The British Library, London; MS Yates Thompson 36, fol. 160, ©️ The British Library Board (MS Yates Thompson 36, fol. 160)

Invisible Armour

Commentary by Scott Nethersole and Ben Quash

This miniature illustrates a manuscript of Dante’s Divine Comedy produced in Siena, probably in the second half of the 1440s, for Alfonso V, king of Aragon, Naples, and Sicily. It appears at the bottom of fol. 160, on which begins canto 18 of the Paradiso.

On the face of it, this miniature has little to do with Joshua and even less with the narrative of Joshua 6.

On the left-hand side, the pilgrim Dante and his beloved Beatrice ascend to the heaven of Mars, on the fifth leg of their journey through the nine celestial spheres. Mars is depicted within the circle of his heaven wearing armour and a winged helmet, and from the outer rings of the circle protrudes the figure of Cacciaguida—an ancestor of Dante who had perished in the second Crusade.

But as canto 18 of Dante’s poem unfolds, Cacciaguida indicates eight holy warriors who appear in the form of a fiery cross: Joshua; Judas Maccabeus; Charlemagne; Godfrey of Bouillon; Robert Guiscard; Roland; William, Count of Orange; and Renouard.

Though it is not easy to identify with certainty each of the eight figures in Giovanni di Paolo’s depiction of this cross, it is Joshua who appears at the top, holding the sun which he commanded to stand still on the day the Lord gave the Amorites to Israel (Joshua 10:12–14). He is the first of the blessed warriors of the faith (Paradiso 18.38).

Christian commentators long before Dante viewed Joshua’s military prowess as secondary to his faith, and his victories as first and foremost victories in a spiritual war. Though accomplished in advance of the crucifixion, these victories were, for the commentators, won under the sign of the cross, and were thus a model for Christian believers.

Though we appear unarmed in body, we nonetheless are bearing arms with which even in time of sunny peace we grapple in spirit against the unsubstantial foe. Now we need God to help us, and him only we must fear; without him our armor falls from us, but with him our armor gains strength. (Paulinus of Nola, Poem 26.99–114)

Dante’s encounter with Joshua, visualized in this illumination, shows the warrior’s true ‘walls’ as the borders of the cross within which he and the other warrior-worthies are contained. Unlike those of Jericho, these defences are impregnable, for Christ ‘will be your wall where there are no walls’ (ibid).

References

Bollati, Milvia. 2006. La Divina Commedia di Alfonso d’Aragona, re di Napoli, 2 vols, (Modena: F.C. Panini)

Pope-Hennessy, John. 1993. Paradiso: The Illuminations to Dante’s Divine Comedy by Giovanni di Paolo (London: Random House)

Walsh, P. G. (trans.). 1975. The Poems of St Paulinus of Nola, Ancient Christian Writers, 40 (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press)

Unknown artist

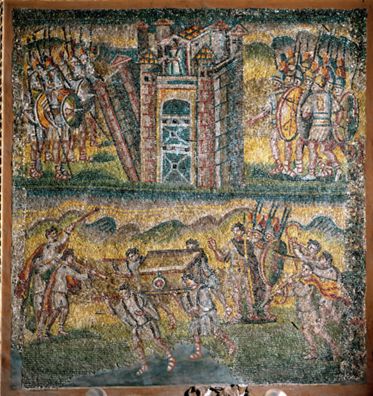

The Taking of Jericho, from the Joshua Cycle, 432–40, Mosaic, Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome; ©️ Luisa Ricciarini / Bridgeman Images

Bearing the Future

Commentary by Scott Nethersole and Ben Quash

This scene of Jericho’s destruction comes from one of the earliest surviving cycles of figurative decoration in Christian art, and certainly the earliest to survive in Rome. The mosaics at Santa Maria Maggiore were made between 432 and 444 CE.

Of the original forty-two scenes (twenty-one scenes to each side of the nave), only twenty-seven have survived. They show the lives of the Patriarchs, the Exodus from Egypt, and the Conquest of the Promised Land, including this scene from the book of Joshua. Over the presbytery (or triumphal) arch are additional scenes from the infancy of Christ.

So Old and New Testaments are combined into a single cycle and do not seem to relate to one another in typical typological terms. In the nave, the cycle begins with Abraham, rather than Adam. As such, it has been argued that the iconography of the basilica can be explained by God’s promise to Abraham in Genesis 22:17 that he would ‘multiply his descendants’ (Folgerø 2009: 33–64; Spain 1979: 518–40). Abraham’s ‘seed’ would pass through David to Mary (who was defined as ‘God-Bearer’ at the Council of Ephesus in 431 CE, just before this church was built in her honour), and thence to Christ. Thus, the Old Testament cycle on the nave walls culminates in the Word made flesh on the triumphal arch.

Our focus in this exhibition is on panel 15. The narrative proceeds from the bottom upwards, with the lower section showing the procession of the Ark of the Covenant around the walls, while the trumpeters—four, rather than seven—sound their instruments, and Joshua addresses his people (Joshua 6:12–19). Jericho falls to Joshua in the upper section (6:20–25), indicated symbolically with an entire section of the city walls collapsing.

The ‘harlot’ Rahab is shown within the city, gesturing towards the invading army (portrayed like the Roman soldiers who would have been familiar to the basilica’s decorators). As the willing assistant of the Israelites, who helped their spies secretly to ‘breach’ the city walls in advance of those walls’ very public collapse, she is a crucial agent in allowing the story to go forward. Like Abraham, she will be celebrated as faithful in both Jewish and Christian traditions. And like Mary—if she is the same Rahab as is mentioned in Matthew 1:5—she will herself be a forebear of Christ.

References

Cecchelli, Carlo. 1956. I mosaici della basilica di S. Maria Maggiore (Turin: ILTE)

Folgerø, Per Olav. 2009. ‘The Sistine Mosaics of S. Maria Maggiore in Rome: Christology and Mariology in the Interlude between the Councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon’, Acta ad archaeologiam et artium historiam pertinentia, 21(7 N.S.): 33–64

Spain, Suzanne. 1979. ‘“The Promised Blessing”: The Iconography of the Mosaics of S. Maria Maggiore’, Art Bulletin, 61.4: 518–40

Lorenzo Ghiberti

Joshua and Jericho, from Gates of Paradise, 1425–52, Gilded bronze, The Baptistry, Florence; Azoor Photo / Alamy Stock Photo

Gossamer Walls

Commentary by Scott Nethersole and Ben Quash

Lorenzo Ghiberti, along with his patrons and advisors, condensed the book of Joshua into two scenes: the crossing of the Jordan with the carrying of twelve stones from its bed (Joshua 4), and the fall of Jericho (Joshua 6). Both are represented on the set of gilt-bronze doors that Ghiberti made for the Baptistery in Florence.

The Old Testament cycle on these so-called ‘Gates of Paradise’ balanced the New Testament cycle on the North Doors (also by Ghiberti) and Andrea Pisano’s life of John the Baptist on the South Doors (as befitted a baptistery). Each of the ten panels tells an entire story though multiple vignettes, as if a ‘chapter’ (Krautheimer 1956: 175).

Compositionally, the two scenes from Joshua are clearly distinguished. The lower, and earlier, episode of the river-crossing is in higher relief. The rocky bed of the Jordan then leads the eye upwards to the second episode at Jericho, whose identity is clearly labelled on the walls (‘GERICO’). This moment is in lower relief, separated from the events beneath it by a coppice of trees and the Israelite encampment.

Jericho’s towers have already begun to tumble and great fissures have opened within the walls themselves. Unlike the hefty rocks in high relief in the foreground, these fragile stone structures are little more than incised lines on the plane of the panel.

They invert the logic of sculpture itself, for those rocks which most approximate untouched nature are, in fact, those which have been most prominently cast—‘built up’ by the artist, not carved away. Meanwhile, the linear forms of the humanly ‘built-up’ city walls are, paradoxically, created by a process of incision.

Such inversions can be read as an appropriate counterpart to the Joshua narrative’s catalogue of changes of fortune, shifts of power, and reversals of the expected, concentrated above all in a fortified city brought down by priests rather than men-of-arms (though men-of-arms soon play their bloody role). Stones are split asunder by the rituals of worship, as powerless as gossamer to defend those they shelter. No surprise that Christian commentators have made christological points from such inversions:

[W]herever Christ is with us, a web is a wall; for the person without Christ, a wall will become a web. (Paulinus of Nola, Poem 16.129)

But a darker paradox also lurks here as an indelible mark is made on history by an act of wiping out.

References

Krautheimer, Richard. 1956. Lorenzo Ghiberti, vol. 1 (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Radke, Gary. M. (ed.). 2007. The Gates of Paradise: Lorenzo Ghiberti's Renaissance Masterpiece (Atlanta: Yale University Press)

Walsh, P. G. (trans.). 1975. The Poems of St Paulinus of Nola, ACW 40 (Mahwah: Paulist Press)

Giovanni di Paolo :

Miniature of Dante and Beatrice ascending to the Heaven of Mars, from Dante Alighieri Divina Commedia, Paradiso XVIII, c.1450 , Illumination on parchment

Unknown artist :

The Taking of Jericho, from the Joshua Cycle, 432–40 , Mosaic

Lorenzo Ghiberti :

Joshua and Jericho, from Gates of Paradise, 1425–52 , Gilded bronze

Metamorphosis of a Massacre

Comparative commentary by Scott Nethersole and Ben Quash

The sixth chapter of Joshua narrates the fall of Jericho. It is the culmination of a campaign that begins in the second chapter when Joshua dispatches spies to enter the city walls and that ends with a massacre: ‘Then they utterly destroyed all in the city, both men and women, young and old, oxen, sheep, and asses’ (Joshua 6:21).

Despite such violence, which results in the total obliteration of Jericho, depictions of Joshua 6 seldom dwell on the Israelite general’s brutality and ruthlessness, as all three artworks in this exhibition confirm. Indeed, two of them—the mosaic from Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome and the baptistery doors in Florence—are part of larger cycles that have quite different agendas and emphases.

The mosaic sequence takes the narrative arc of Joshua 1–6 and reduces its key motifs and characters—the figures of Joshua, his spies and Rahab, the castle-like city of Jericho, and the Ark of the Covenant—to a series of visible patterns, easily recognised from far below in the nave. The emphasis on Rahab is notable. Panel 15, which is illustrated here, includes two different viewpoints, both of which pivot on her, but from diametrically opposed positions. In the lower scene, the procession of the Ark around the walls is viewed as if from within the city. The viewer’s gaze would seem to be elided with that of Rahab. By contrast, in the upper scene in which the walls collapse, she stands at the centre of the composition, looking out.

The designer has chosen to emphasize the individual who, together with her kin, was spared, rather than stress the violence and destruction that Joshua unleashed on the people of Jericho. In this papal basilica dedicated to Mary, whose cult was reaching new heights, Rahab’s preservation may subtly link with Mary’s. Though a brothel was Rahab’s home, she was, for theologians of the early Church, a ‘rose of piety hidden in thorns’ (Chrysostom Homilies on Repentance and Almsgiving 7.5.15–16): a possible precursor of the ‘Mystic Rose’ preserved in purity to be the mother of God.

Like the mosaic, Lorenzo Ghiberti’s depiction too is relatively free of horror. The walls come down, as the Ark, the trumpeters, priests, and Israelites process around it, but there is no suggestion of the events that are to ensue.

Both this bronze relief and the mosaic at Santa Maria Maggiore ‘read’ from bottom upwards, though here, within the terms of the artist’s brilliantly realized illusion, from the foreground backwards as well. The fall of Jericho is, in other words, consigned to the background. Ghiberti gives far greater prominence to the scene in which the Ark is carried across the Jordan and the Israelites collect stones, emphasizing events that led up to the siege, than to the violence of the sack itself. This focus might seem surprising, especially since Joshua was understood as a model of righteous military action in early fifteenth-century Florence (Bloch 2016). Martial exemplars found much favour in a city often threatened by larger states. However, the miracle that stopped the waters of the Jordan to allow the Ark to pass was interpreted as a precedent for baptism and could not have been more appropriate for the doors of the baptistery. The fall of Jericho was, therefore, made subsidiary to a focus on other themes.

Ironically, of the three scenes presented here, it is the one by Giovanni di Paolo in which Joshua is most obviously celebrated for his military achievements, despite being almost free of any narrative, and certainly free of any reference to his destruction of Jericho.

The Nine Worthies of medieval Christian tradition normally combined three Jews, three pagans, and three Christians, but Dante alters the company to include more Christians and some fictional characters. While some of the heroes are the central protagonists of Carolingian epic, others fought the Saracens—a theme of conflict between Christianity and Islam that Dante anticipates at the end of Paradiso 15.

It could be argued, then, that Joshua was for Dante the first crusader; the first to return the Holy Land to its rightful people, even if those people differ between the Old Testament and the Comedy.

Ghiberti dressed Joshua in armour as the epitome of the divinely protected warrior, favoured by God. The mosaicist in Santa Maria Maggiore presents him as a Roman general. Giovanni di Paolo depicted him in close proximity to Mars, and even dressed him in the same costume.

All three artists turn a blind eye to the violence Joshua unleashed. But the smell of blood is not far away.

References

Bloch, Amy R. 2016. Lorenzo Ghiberti's Gates of Paradise: Humanism, History, and Artistic Philosophy in the Italian Renaissance (Cambridge: CUP)

Christo, Gus George. (trans.). 1998. St John Chrysostom. On Repentance and Almsgiving, The Fathers of the Church: A New Translation, 96 (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press), pp. 98–99

Réau, Louis. 1956. Iconographie de l’art chrétien, 3 vols (Paris: Presses Universtiaires De France)

Dartmouth Dante Project. Available at: https://dante.dartmouth.edu/ [accessed 28 June 2022]

Commentaries by Ben Quash and Scott Nethersole