2 Samuel 21; 1 Chronicles 20:4–8

Rizpah and her Children

Robert Mabon

Scene in Famine, 18th century, Watercolour and graphite with pen and black ink on paper, 79 x 64 mm, Yale Center for British Art; Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.22369, Courtesy of Yale Center for British Art

An Untended Corpse

Commentary by Wil Gafney

2 Samuel 21 begins with a notice of famine. And from the hand of Robert Mabon, whose career spanned the years from 1792 to 1798, comes a stark illustration of just that.

This pen and ink drawing is entitled Scene in Famine (one of at least two works with that title by the artist). With washed out watercolours in slate and sand and grey, Mabon depicts a supine man dying or dead, being eaten by birds of prey and what is perhaps a dog. The man’s famine-bloated belly and the aggression of his eaters communicate the horror of famine. He may be being eaten alive: his uplifted chin and bent but still upright left leg suggest there may yet be some life left in him. But not for long. A large white bird stands on his head, preparing to peck or rip at the soft tissues of his face. A second bird, grey, is captured in descent, coming to partake of the gruesome meal. The rough sketched canid has already torn into the man’s breast; there is flesh in its mouth.

Read alongside the story of Rizpah—defending the bodies of her children from carrion eaters—the presence of a dog would be an additional horror. Dogs were despised in ancient Israel and being eaten by a dog was the ultimate desecration of the human body (see 1 Kings 14:11; 16:4; 21:19, 23–24; 22:38).

Mabon’s untended corpse illustrates Rizpah’s fears—what she sees as she moves from the body of one dead child to the remains of the other. As Rizpah turned to one body, beating back the predators, another would have been exposed, and the carrion eaters would feast. Their ages are not revealed in the text; their ages do not matter to the authors or perhaps even to Rizpah. These are her babies, whether children in arms or fully grown men like Mabon’s subject.

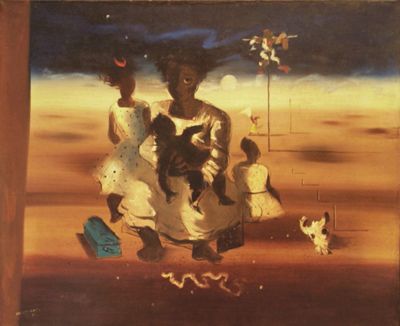

Candido Portinari

Woman with Children, 1940, Oil on canvas, 51 x 71 cm, Private Collection; AGB Photo Library / Alamy Stock Photo

Deserted in the Desert

Commentary by Wil Gafney

Brazilian painter Candido Portini’s (1903–62) Woman With Children depicts an Afro-Brazilian woman in shades of brown and black.

The woman may be read as Rizpah bat Aiah with her children sitting in a barren landscape representing her lack of protection and provision, images of death all around them; a prelude to the events of 2 Samuel 21.

The scene is punctuated by a cow skull and a scarecrow. These are alarming images. The little family is not safe. The mother looks the viewer in the eye needing help but not quite asking for it. To her right and left are larger and smaller girls facing backward—looking back, perhaps to the place from which they have come, as did Lot’s wife in Genesis 19:26.

On her lap she holds an infant seemingly in full wiggle. She sits on a box, perhaps a piece of luggage and there is a smaller box near her, perhaps a lunchbox. In my reading, the father of her children has just died and been replaced by a new king. Rizpah and her children are on their own. The warm, red-earth and browns of the desert give way to a deepening night sky; there is no shelter to be seen. The girls’ polka-dotted dresses contrast with their mother’s plain one. Their mother has given them what gifts she can. One girl has a red ribbon—the only splash of colour in the painting—slipping from her unravelling hair as the colour seeps from Rizpah’s unravelling life.

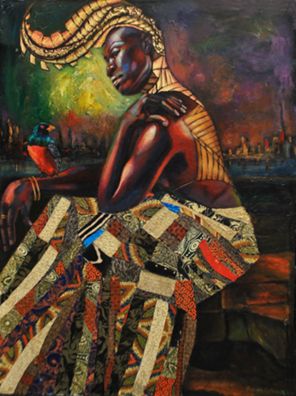

Tamara Madden

Keeper of the Golden City, 2013?, Mixed media on canvas, 91.5 x 122 cm; Courtesy of the Tamara Natalie Madden Estate

The Keeper of the Dead

Commentary by Wil Gafney

In 2013, Atlanta based, Jamaica born Tamara Madden (1975–2017) released a series of mixed media ‘Guardian’ images on canvas with lush depictions of Africana women ornamented with rich gilding.

The woman in The Keeper of the City invites comparison with Rizpah bat Aiah in 2 Samuel 21. Her left hand draws the eye as she rubs her left shoulder, her elbow resting on one knee, seated on a rock. It is a posture that evokes how an aching Rizpah keeps vigil on the rocks as she guards the remains of her children from carrion eaters (2 Samuel 21:10).

The body of Madden’s ‘Keeper’ slants forward but her back is straight and her head is lifted up. Her beautiful face is composed, sorrowful, exhausted, determined. Her back is girded and gilded with bars of gold. The city is at her back; she has turned away from it. Read with 2 Samuel 20:3, the city in the painting can assume the mantle of Jerusalem where the man lives who handed over Rizpah’s children to pay a blood debt they did not owe (2 Samuel 21:8–9).

Her right arm rests on the corresponding knee and her hand dangles signaling exhaustion. A black bird with a bright red chest sits on her right arm just above her wrist encircled by delicate bracelets, which—with the matching rings on her finger—can be imagined to be gifts from the king who fathered her sons. (I do not identify the men and kings in this passage; this exegesis is not about them.) The bird is most likely a red-breasted meadowlark from the artist’s native Caribbean. In my visual exegesis accompanied by 2 Samuel 21, the bird is one of those that came to feast on her children’s remains. She has not only dissuaded it, she has tamed it. It will not partake of that unjust feast.

References

Gafney, Wilda. 2017. Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and of the Throne (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press), pp. 198–201

Robert Mabon :

Scene in Famine, 18th century , Watercolour and graphite with pen and black ink on paper

Candido Portinari :

Woman with Children, 1940 , Oil on canvas

Tamara Madden :

Keeper of the Golden City, 2013? , Mixed media on canvas

Mother of the Dead

Comparative commentary by Wil Gafney

Visual exegesis—particularly iconographic representations of biblical characters and other holy figures—can offer rich insights into biblical interpretive practices across times and cultures. In the present reading, three disparate works of art offered provide depth and texture to 2 Samuel 21, itself part of a longer continuing story. This suite of images works well when reading this ancient story because the motifs are enduring and because interpretation is as much the province of the reader/viewer as it is the writer/painter.

The narrative opens with an ecological and economic crisis: famine. For three years, ‘year after year’, the famine persisted (2 Samuel 21:1). Bloated, mangled bodies like Robert Mabon’s subject in Scene in Famine would have been commonplace.

The biblical narrator’s God blames the now dead Saul. His guilt lingers; his defamation, even beyond the grave is a key element in the pro-Davidic propaganda of the Samuel corpus. The unnamed David devises a plan without consulting his God (vv.2–6). It is his (or the narrator’s) theological understanding that atonement must be made using the verb that gives Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, its name, (the NRSV has ‘expiation’ instead; v.3). David seeks the blessing of the Gibeonites (the objects of Saul’s earlier hostility), suggesting an understanding that their blessing will somehow end the famine, a blessing he will purchase with blood, with the lives of Rizpah’s children along with the children of other mothers, all descendants of the vilified Saul.

Saul’s death occasioned a wilderness of abandonment, transition, and desperation for Rizpah as a low-status wife whose children were not entitled to an inheritance. This wilderness is evoked by Candido Portini’s Woman with Children. (Secondary or low-status wives were legal wives and not concubines; see Gafney 2017: 34, 77–78, 198).

A reading of the passage using Tamara Madden’s The Keeper of the City conjures, by contrast, the resolve of Rizpah, blossoming into an unimaginable strength. Sitting outside of the city that turned its back on her and her children, Rizpah, mother of the dead, keeper of the dead, becomes the keeper of the city. The famine ends when her watch ends, with the rightful burial of the dead in 2 Samuel 21:14.

References

Gafney, Wilda. 2017. Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and of the Throne (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press)

Commentaries by Wil Gafney