Exodus 19

Sinai Calling

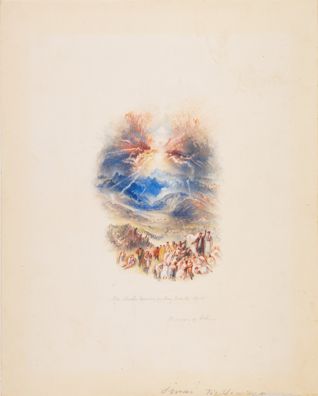

Joseph Mallord William Turner

One of Twenty Vignettes, Sinai's Thunder (Illustration to 'The Pleasures of Hope'), c.1835, Watercolour over pencil on paper, 125 x 95 mm, National Galleries of Scotland; Accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax and allocated to the National Gallery of Scotland, 1988, D 5156, Courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland

Sinai Past

Commentary by Amy L. Balogh

The drama of Joseph Mallord William Turner’s Sinai’s Thunder is, arguably, outdone only by the biblical text itself. Immediately, our eyes are drawn to the deity enshrouded in the storm from which angular bolts of lightning direct us towards the earth below. There, the Israelites prostrate themselves upon hearing the divine word shared with them by Moses.

The Israelites form a line that winds organically from the foreground into the far distance and directs our attention back to the foot of the mountain—the front row of the theophany—which then points us upward to where we began.

The deity’s upraised arm and head interrupt the spectacle of cloud, thunder, lightning, and fire, evoking the idea found in other biblical theophanies that YHWH is simultaneously wholly other and a bit like us, the paradox of a cosmic force desiring proper relationship with a chosen community (cf. Exodus 33:12–34:9; 1 Kings 19:9–18). The position of Moses’s left arm mirrors that of the deity, suggesting their solidarity in word and purpose.

On the first day, YHWH opens this conversation saying, ‘You have seen what I did to the Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles’ wings and brought you to myself’ (Exodus 19:4). The metaphor of eagles’ wings, echoed visually by the split in Turner’s clouds, also evokes the deity’s parental instinct toward the people of Israel (cf. Deuteronomy 32:10–11, where YHWH hovers over ‘Jacob’ like an eagle over its young). In light of this eagle-like quality, YHWH issues a call to responsibility, ‘Now therefore, if you obey my voice and keep my covenant, you shall be my treasured possession out of all the peoples’ (19:5). The people accept the challenge with solidarity (v.8). On the third day, the spectacle begins (vv.9, 16).

But why is the theophany necessary if the deity has already obtained Israel’s agreement? YHWH explains to Moses that it is, ‘in order that the people may hear when I speak with you and so trust you ever after’ (v.9). It is not so that the people will believe in YHWH; it is so that they will believe Moses.

The sights and sounds of that day establish the divine origin of the words that Moses would speak to the people over the next forty years, that would eventually be written down, and that the world would come to respect if not follow. Through the divine word, Sinai thunders for all time.

Francis Frith

Mount Horeb, Sinai, 1858, Albumen silver print, 379 x 484 mm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; 84.XM.633.15, Digital image courtesy of the Getty Open Content Program

Sinai Still

Commentary by Amy L. Balogh

Today, Mount Sinai is still. The theophany that made her famous ceased long ago, yet the rumbling of YHWH's voice still moves in the interior worlds of those who trust the divine words shared that day.

The atmosphere in English photographer Francis Frith’s Mount Horeb, Sinai conveys the essence of Sinai as it appeared in the mid-nineteenth century; as both an ordinary mountain and a sacred space that—along with the people of Israel—once trembled in the presence of YHWH (Exodus 19:16, 18). While silent, she stands as a testimony to YHWH's eternal promise that, because the earth is his, those who obey his voice and keep his covenant will be his ‘treasured possession out of all the peoples’ (v.5).

The solitary figure in the foreground reminds us how much has changed since the Israelites set up camp at the foot of the mountain (v.2)—the original 600,000 men plus women, children, a ‘mixed multitude’, and ‘very much livestock’ (12:37–38) are gone. This person, like many travellers and pilgrims since the exodus, has come to the mountain on his own.

He seems to be maintaining his distance from the place so holy that to touch it once resulted in death (19:12–13). This is in contrast to Moses, who ascends the mountain no less than three times in the course of this one chapter—activity which speaks volumes to his physical and spiritual suitability for the unique challenges ahead (vv.3, 8, 20).

The theophany of Exodus 19 is only one reason for Sinai’s significance in the religious imagination. It is also widely identified with Horeb, where Moses first encounters YHWH in the burning bush (Exodus 3–4). The Mount Sinai Monastery, situated in the valley just left of Frith’s mountain, is built around the traditional location of that bush. The monastery dates back to the third century CE and guards the spiritual inheritance that Sinai has bestowed on humanity through various Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions. Renowned for its icons, manuscript collection, and deep spiritual history, the monastery symbolizes the continuous power of theophany to change our individual and collective worlds long after the spectacle ceases. Whether mountain or homo sapiens, one is never the same after an encounter with the divine.

References

Silvia, Adam M. n.d. ‘Holy Land Photography: Mid-19th Century Photos of the Middle East by Francis Frith’, www.loc.gov [accessed 22 September 2020]

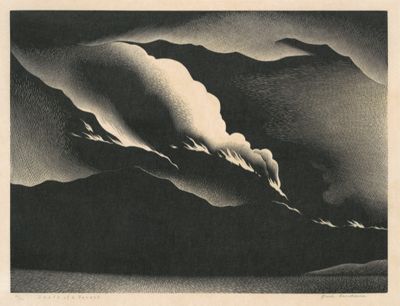

Paul Landacre

Death of a Forest, 1938, Wood engraving on black on wove paper, 269.9 x 282.6 mm (sheet), National Gallery of Art, Washington DC; Gift of Bob Stana and Tom Judy, 2015.115.29, © 2020 Estate of Paul Landacre / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; photo: National Gallery of Art, Washington

Sinai Future

Commentary by Amy L. Balogh

Paul Landacre’s engraving tells of a theophany of a different kind from what Joseph Mallord William Turner and Francis Frith (both also featured in this exhibition) envision. While it does not represent Sinai, the fire and smoke of Death of a Forest evoke the biblical author’s description of the mountain as ‘wrapped in smoke, because the Lord had descended upon it in fire; the smoke went up like the smoke of a kiln’ (Exodus 19:18). The same divine presence that serves as a positive force for the good of humankind seems a destructive force in its effects on the mountain. We may imagine the fire of YHWH like a wildfire—burning vegetation and wildlife without warning. It causes such upheaval as to elicit a violent response from the mountain’s very core: ‘the whole mountain shook violently’ (v.18).

In Exodus 19, Nature is just as involved in the theophany as YHWH or Israel. The episode begins on a new moon (v.1), is located in the desert wilderness (vv.2, 3), and requires the people to wash their bodies and clothing with precious water (vv.10, 14), while YHWH manifests using dense cloud (vv.9, 16), thunder (vv.16, 19), lightning (v.16), fire (v.18), and smoke (v.18)—some of nature’s most ominous phenomena. Thunder is the very voice of God (v.19). The mountain itself, mentioned fourteen times in 19:11–23, bears witness to the terror of theophany, trembling with a holy charge so great that any human or beast who touches it becomes a danger to the entire community (vv.12–13, 21–24).

The inclusion of animals in the prohibition against touching the mountain underscores how all species are equally beholden to the power of YHWH. Today, as species vanish and mountains burn with the fire of humanity’s presence, Sinai calls homo sapiens to remember that the natural world both bears and bears witness to the divine presence on earth. Its degradation at the hands of humankind stands in contrast to our humble position alongside the animals at Sinai. Nature, too, is part of the divine story and it serves us all well when we remember that.

Joseph Mallord William Turner :

One of Twenty Vignettes, Sinai's Thunder (Illustration to 'The Pleasures of Hope'), c.1835 , Watercolour over pencil on paper

Francis Frith :

Mount Horeb, Sinai, 1858 , Albumen silver print

Paul Landacre :

Death of a Forest, 1938 , Wood engraving on black on wove paper

Sinai Still Thunders

Comparative commentary by Amy L. Balogh

The theophany at Sinai is the linchpin of the book of Exodus, serving as both the culmination of the Hebrews’ liberation from the tyranny of Egypt and the preamble to YHWH's pronouncement of the terms of their collective relationship. The divine word could have come to Moses in a whisper, as it later does when the prophet Elijah meets YHWH at Sinai (1 Kings 19:12–13), but it does not. Instead, it comes with fire, smoke, and a thunder that shakes mountains.

The legitimacy of this divine word is the raison d’être of the theophany. With the descent of YHWH at Sinai, the relationship between YHWH and Israel pivots from one of redemption to one of responsibility in light of that redemption.

The connection between divine salvation and the way we live is an essential theme of the Bible from beginning to end but is perhaps no more explicit than here. YHWH's ‘now therefore’ (v.5)—establishing and perpetuating the idea that YHWH liberates the Hebrews from something unto something else—reverberates like a resounding gong in this passage. The pivot from the tyranny of Egypt to life with YHWH in their midst is no small event in Israel’s history.

The spectacle accompanying YHWH's descent occurs solely that the people may hear YHWH speak to Moses and thus believe Moses forever (v.9). In impressing the memory of theophany upon the reader, the author makes an argument not only for YHWH but for Moses as mediator of the divine word and thus for the divine word itself. How does one access that divine word? Through engaging with the book of Exodus. The revelation at Sinai is both a one-time event and an event that occurs in perpetuity, every time someone picks up the book and reads. This pairs well with the tradition that all past, present, and future Jewish souls were present at the moment of revelation at Sinai (Midrash Tanhuma Nitzavim 3; Babylonian Talmud Shevu’ot 39a).

The idea of Sinai as both past and perpetual is the foundation of the Jewish Passover (Pesach), a seven-day celebration that memorializes both the exodus out of Egypt and the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai. Passover is also closely linked to the Christian story of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, as Jesus’s Last Supper takes place on the evening when Passover begins (Matthew 26:17–19; Mark 14:12–16; Luke 22:1–16) and his death occurs on the first full day (John 18:28–40). In this way, both Judaism and Christianity connect their adherents’ lives to Sinai’s call to live in light of one’s salvation.

The spirit of Mount Sinai finds itself expounded by Turner, Frith, and Landacre. Each artist’s work helps to highlight a different facet of the spiritual life of this geological feature. Turner’s figural representation conveys the drama of the moment, fiery and awesome, invoking a wide array of responses from those in attendance. Frith draws our attention to the historical importance of Sinai as a place of religious pilgrimage for Jews, Christians, and Muslims. Landacre’s engraving—while not depicting Sinai directly—can open our imagination to another side of Sinai, prompting us to think about the experience of nature and the implications of that experience for rethinking our relationship to the earth.

Together, Turner’s, Frith’s, and Landacre’s works illustrate that time and the mountain move on.

Although it looks like any other mountain in the region, Sinai has never been—nor will it ever be—the same as them. As long as the Bible or any one of the Abrahamic traditions endures, it will be remembered as the place where YHWH manifested himself in the sight of all Israel. The thundering of the deity’s voice rises for one reason and one reason alone: that the people might hear his word, find it trustworthy, obey, and become his treasured possession (19:4–5, 9)—in each new generation.

Why? ‘For all the earth is mine’, says YHWH (v.5). Because it is his, Sinai calls us to live with reverence and with the memory that the mountain trembled along with us and the beasts stood by our side in witness to the terror of that which we could not touch either literally or figuratively. As long as the mountains endure, Sinai stands as the reminder that all of creation trembles in the presence of the divine, yet what we do matters. It always has and it always will.

Commentaries by Amy L. Balogh