Numbers 13

Spies Sent into Canaan

Unknown artist

The Grapes from the Promised Land, from Historienbibel by Ulrich Schriber, 1422, Manuscript illumination, Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg; 2 Cod 50 (Cim 74), fol. 105r. (p. 211), Courtesy Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

Fearing the Other

Commentary by Rembrandt Duits

Numbers 13:23, which describes two Israelite spies who carry an over-sized bunch of grapes from the brook of Eshcol in Canaan back to the Israelite camp, is the most consistently illustrated verse of this section of the book of Numbers.

This is a relatively early variant, made in Strasbourg in Alsace in 1422, stemming from a historiated Bible or bible historiale, a popular late-medieval reworking of Scripture in vernacular prose. Such Bibles offered a summary of the biblical narrative accompanied by a suite of illustrations. The caption states that ‘here, two carried a bunch of grapes on a pole and spotted a giant, which, however, gave them a great and bad scare’, capturing the outcome of the reconnaissance mission into the Promised Land: great fruits but inhabitants you do not want to mess with.

At first, the image seems a straightforward visual interpretation of the story, albeit translated to a medieval environment. The two spies, in fifteenth-century tunics and hose, walk through a verdant landscape. A central-European walled city with a prominent gate is visible in the background. The grapes they bear are green, perhaps reflecting the local varieties of the Alsace region. The heavily bearded giant on the left wears full gilded armour over a crimson tunic with the long dagged sleeves that were in fashion with the nobility in the 1420s. He could be the equivalent of a threatening local robber baron.

There may, however, be a subtle, more disturbing layer to this image. The spy furthest away from the spectator wears a typical pointed hat (or pileus cornatus) that is often used as a discriminating mark of Jewish people in northern European pictures of the time. The fact that his companion has more regular style headwear and is not singled out as a Jew may indicate that the image reflects an existing allegorical reading of the passage (known from the fourteenth-century Speculum humanae salvationis). In this interpretation, the grapes refer to Christ (whose blood became the wine of the Eucharist) and the two spies stand for the Jews and the Pagans whom medieval commentators accused of together putting Christ on the Cross. Thus, for a medieval Christian viewer, not just the giant but the entire population of the image may have consisted of those they regarded as hostile aliens, with only the grapes offering salvation.

References

Bodemann, Ulrike. 2017. ‘Historienbibeln. Historienbibel IIa. Handschrift Nr. 59.4.1’, in Katalog der deutschsprachigen illustrierten Handschriften des Mittelalters (KdiH) vol. 7, available at http://kdih.badw.de/datenbank/handschrift/59/4/1 [accessed 7 March 2024]

Gier, Helmut and Johannes Janota (eds). 1991. Von der Augsburger Bibelhandschrift zu Bertolt Brecht. Zeugnisse der deutschen Literatur aus der Staats- und Stadtbibliothek und der Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg (Weißenhorn: Konrad Anton)

Wilson, Adrian and Joyce Lancaster Wilson. 1985. A Medieval Mirror. Speculum Humanae Salvationis 1324–1500 (Berkeley: University of California Press)

Nicolas Poussin

Autumn, from the Four Seasons, 1660–64, Oil on canvas, 1.7 x 160 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris; INV 7305 ; MR 2340, ©️ RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Picturing the Promised Land

Commentary by Rembrandt Duits

Between 1660 and 1664, the French painter Nicholas Poussin, working in Rome since 1624, completed his final commission. Made for the Duc de Richelieu, the grand-nephew of Cardinal Richelieu of three-musketeers infamy, it consisted of a set of four paintings showing the four seasons.

The cycle of the seasons was a common theme in European art. Other artists had rendered it using landscapes, allegories, or sometimes classical gods. Poussin opted, instead, for an unusual combination of four subjects from the Old Testament: Adam and Eve in Paradise represent Spring; Ruth and Boaz among the wheat fields Summer; and the devastation of the Deluge Winter. For Autumn, Poussin selected the grape harvest of Numbers 13:23.

Poussin styled himself as a learned artist and his version of the verse stays close to the text. The spies enter Canaan when the fruits are ripe: there is a woman standing on a ladder picking apples from a tree in the background. Another woman with a laundry basket on her head walks by a stream flowing on the right: presumably the brook of Eshcol. The two spies carry their grapes on a pole, but the one on the right also holds other produce: the pomegranates and figs mentioned in the verse. The painting demonstrates how classical Antiquity had made an impact on art in the preceding two centuries. We see this if we compare it with the historiated Bible’s illustration of the same scene, discussed elsewhere in this exhibition. The clothes of the figures are inspired by antique statues, and the Mediterranean valley in which the scene plays out breathes the calm of ancient Arcadia.

The seasons aside, Poussin’s series also depicts the times of the day, from bright morning in Paradise via a sun-drenched noon in the episode with Ruth and Boaz, to a moonlit night for the Flood. This autumn scene is bathed in a golden evening glow that adds to the elegiac atmosphere. The menace of the giants which is so prominent in Numbers 13 is completely absent here. The only hint that not all is well is in the grim faces of the grape-bearers. They look decidedly concerned—either by a massive Son of Anak whom we may imagine lurking outside the frame, or possibly in a distant echo of the medieval exegesis that equated the two spies and their grapes with those responsible for the crucifixion of Christ.

References

Blunt, Anthony. 1967. Nicholas Poussin (London: Phaidon Press)

Milovanovic, Nicolas. 2021. Catalogue des peintures françaises du XVIIe siècle du musée du Louvre (Paris: Gallimard–Louvre éditions)

Rosenberg, Pierre. 1908. Poussin and Nature. Arcadian Visions (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

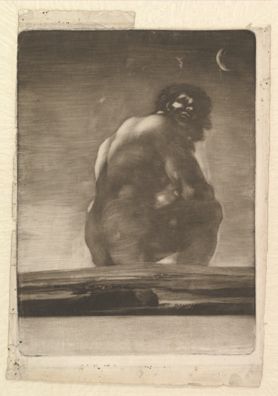

Francisco de Goya

Seated Giant, By 1818 (possibly 1814–18), Burnished aquatint, scaper, roulette, lavis (along the top of the landscape and within the landscape), 284 x 208 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935, 35.42, www.metmuseum.org

Fear Itself

Commentary by Rembrandt Duits

Europeans of the fifteenth and even of the seventeenth century might have related to the story of the spies confronted by giants in the Promised Land by thinking of voyages to, and exploration of, unknown places in the world; places where actual giants might live. By 1800, however, the unmapped areas of the globe had dramatically shrunk. At the same time, the early nineteenth century saw artists begin to abandon traditional themes such as ‘the four seasons’ and start to present more personal responses to the events of their time. They also experimented with techniques that allowed greater freedom of expression, such as the aquatint method, which changed printing from a line-based medium into one capable of more painterly nuances of light and shade.

All these trends seem to converge in the dramatic aquatint of a seated giant that the Spanish artist Francisco Goya (1746–1828) made in the later decades of his life. Goya earned a reputation as a portraitist at the Spanish court but turned to darker subjects in his private works, especially in print, with his often nightmarish series of Capriccios and the gruesome Disasters of War, inspired by the Napoleonic Wars in Spain (1807–14).

The seated giant, although a standalone sheet rather than part of a sequence, belongs with these brooding reflections. It is often thought the dark titan resting on the horizon of a moonlit landscape represents the threat of war, but it is equally possible that Goya created an associative image out of blotches (a bit like a Rorschach Test) when playing around with the aquatint medium.

One could argue that the reading of the print as a warning against war is almost too directly allegorical. What is striking is the vagueness and the lack of identifiable features. The landscape consists of blurry, imprecise shapes; the giant himself is a shadowy figure merging with the dusk. This is not a giant who inhabits a specific geographical location but one who looms in the half-light of a liminal space, resting on the border between night and day, and between this world and the next. In a sense, Goya sublimely sums up how giants became transformed from supposedly real, if unverified, dangers in foreign lands (as in Numbers 13) to creatures of the imagination, the embodiment of our own fears.

References

Ives, Colta. 2000. ‘The Printed Image in the West: Aquatint’, in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

MacDonald, Mark (ed.). 2021. Goya’s Graphic Imagination (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Unknown artist :

The Grapes from the Promised Land, from Historienbibel by Ulrich Schriber, 1422 , Manuscript illumination

Nicolas Poussin :

Autumn, from the Four Seasons, 1660–64 , Oil on canvas

Francisco de Goya :

Seated Giant, By 1818 (possibly 1814–18) , Burnished aquatint, scaper, roulette, lavis (along the top of the landscape and within the landscape)

Tall Tales

Comparative commentary by Rembrandt Duits

How do people respond to new and unknown worlds? In our own age, this is the domain of science fiction, where authors and film-makers have an unbridled freedom to envisage what we might encounter if we were ever to travel our galaxy at warp speed in starships—life forms in infinite variety, untold treasures, and mortal dangers. Gigantism is frequently a feature of such fantasies: creatures the size of entire planets—on or in which other beings live—are no rare exception in them.

The idea of giants beyond our borders is hardly new. Francisco Goya’s print of a brooding colossus perched on the edge of the world, included in this exhibition, is an earlier but still relatively recent example from a long history of giant imagination. This history can be traced back via Jonathan Swift’s satirical Brobdingnag, found by Gulliver on his travels, to medieval accounts of the Marvels of the East and from there to ancient accounts including the Bible.

One example occurs in Numbers 13, where the Israelites whom Moses has led out of Egypt, after decades of wandering the desert, at long last reach the threshold of the Promised Land. This happens against a background of growing dissent, which will erupt in the following chapter of Numbers, but already comes through in the first, mixed reactions to the Promised Land itself. The years in the desert have taken their toll on morale, and, to the frustration of their almighty but often very human God, some among Moses’s band have not kept the faith. Thinking they have been misled, a few are even arguing that it would be better to return to Egypt.

One problem with the Promised Land, now that the Tribes of Israel have finally arrived, is that it is not pristine. In a situation that will have echoes in many later human migrations, Canaan is already occupied, and right of settlement, let alone ownership, will have to be contested. In Numbers 13, all that happens initially is that Moses sends out spies, one for each of the twelve tribes, to gain intelligence on the lie of the land and its people. The twelve spies disperse and for a period of forty days trek the length and breadth of Canaan before they return to bring out their reports.

The most impressive result is achieved by the two spies who reach the brook of Eshcol, where the soil is apparently so fertile that the local agricultural produce is stimulated to excessive growth. A single bunch of grapes is huge enough that it has to be carried by two people on a stake. Such abundance has an obvious allure, in-keeping with the notion of a Promised Land as it has been dangled in front of the wandering Israelites for so long. It is not surprising that this particular passage from Numbers 13 is the one that has been the most illustrated, with successive artists from the Middle Ages onwards finding inspiration in the graphic image of the two spies walking with a pole balanced on their shoulders supporting a cluster of grapes the size of watermelons. Examples by the medieval German draughtsman of a Picture Bible and the seventeenth-century French classicist master Nicholas Poussin are included in this exhibition.

If the giant grapes represent the dream of a terra as yet incognita where the grass is greener than our own, other spies come back from Canaan with news that—in equal but opposite measure—corresponds to the terror that uncharted territories can inspire. They side with the faction who feel the whole escape from Egypt has been a futile exercise and seek to instil fear among the gathered tribes. Their claim is that it is not only the local flora that has assumed vast dimensions. Ordinary humans venturing into Canaan are at risk of being devoured, and it is pointless to consider taking on the Sons of Anak, who are of such enormous stature that they could crush Israelites like grasshoppers.

Interestingly, these fearsome giants are not often shown in images related to this biblical passage (perhaps because the stories of the spies are treated as deliberate exaggerations). Poussin, for instance, merely envisaged the Promised Land as a bucolic classical landscape. Only the medieval designer of the Picture Bible has added a menacing giant next to the spies bearing the grapes, conceivably because threatening giants in foreign lands were a vivid part of the lore of his own time. The medieval vision of travelling into the unknown was perhaps closest to that of modern-day science-fiction, picturing a variety of different life forms, treasures, as well as mortal dangers.

References

Bonheim, Helmut. 1994. ‘The Giant in Literature and Medical Practice’, in Literature and Medicine, 13: 243–54

Davis, Surekha. 2016. Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human. New Worlds, Maps, and Monsters (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Vitaliano, Dorothy B. 2007. ‘Geomythology. Geological Origins of Myths and Legends’, in Myth and Geology, ed. by L. Piccardi and W.B. Masse (London: Geological Society London Special Publications), pp. 1–7

Watson, G. 2016. ‘Numbers, Book of’, in The Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham: Lexham Press)

Commentaries by Rembrandt Duits