Lamentations 1

Surviving Weeping

Ana Mendieta

Imagen de Yagul, from the series Silueta Works in Mexico 1973–1977, 1973, Chromogenic print, 50.8 x 33.97 cm, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; 93.220, © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. Photo: Don Ross, courtesy of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Lament as Exile and Identity

Commentary by William J. Danaher, Jr.

Taken while working on an archaeological dig in the ruins of a Zapotec tomb, Ana Mendieta’s Imagen de Yagul grapples with the ‘exilic qualities of identity’, the sense of being tied to, and yet separated from, the usual ‘categories’ of gender, race, ethnicity, nation, colony, exile, and home. Lacking a straightforward way to negotiate her experience, Mendieta defines these categories, Jane Blocker writes, ‘only through loss’. There is ‘no essence, only the search for essence; there is no identity, only the search for identity; there is no origin, only the cinder’ (Blocker 1999: 33).

Immersed in a Mexican culture brimming with colonial and indigenous traditions, Mendieta’s ‘earth/body’ art interjects ‘the performing body into nature to forge links with an ancestral past and present’ (Rifkin 2004: 11). Imagen de Yagul therefore speaks authoritatively with the ‘double-voice’ and in the ‘double-time’ of lament. ‘I have been carrying on a dialogue between the landscape and the female body (based on my own silhouette)’, Mendieta writes. ‘I believe this has been a direct result of my having been torn from my homeland (Cuba) during my adolescence. I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature). My art is the way I re-establish the bonds that unite me to the universe’. (Barreras del Rio and Perreault 1988: 10)

Drawing from Santería, which hybridizes Yoruban beliefs with Catholic practices, Mendieta is both a performer and archivist of loss. She lies as dead, waiting for rebirth—a return, she writes, to the ‘unbaptized earth of the beginning, the time that from within the earth looks upon us’ (Blocker 1999: 33). She is covered with flowers, which resonates not only with Catholic burial practices, but also with this larger indigenous cosmology—the contrast of the ruin and the fresh flowers gives ‘the sense’, Mary Jane Jacob writes, ‘of new life sprung from the dead, literally from her body’ (1991: 13).

References

Barreras del Rio, Petra, and John Perreault. 1988. Ana Mendieta: A Retrospective (New York: Museum of Contemporary Art)

Blocker, Jane. 1999. Where is Ana Mendieta?: Identity, Performativity, and Exile (Durham: Duke University Press)

Jacob, Mary Jane. 1991. The ‘Silueta’ Series, 1973–1980 (New York: Galerie Le Long)

Rifkin, Ned. 2004. ‘Forward’ in Ana Mendieta, Earth Body: Sculpture and Performance, 1972–1985, ed. by Olga M. Viso, (Washington, DC: Hatje Cantz)

Sam Gilliam

April 4, 1969, Acrylic on canvas, 279.4 x 456.6 cm, Smithsonian American Art Museum; Museum purchase, 1973.115, © Sam Gilliam; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC / Art Resource, NY

Lament as Fractured Memory

Commentary by William J. Danaher, Jr.

Many criticized Sam Gilliam for failing to create empowering, political images of African-American life. ‘Figurative art’, Gilliam responds, ‘doesn’t represent blackness any more than a non-narrative media-oriented kind of painting, like what I do’ (Binstock 2005: 71). Indeed, Gilliam’s work embodies, Mark Godfrey writes, a ‘Black aesthetic’ that loosened ‘the conventions of painting’ to make room for a ‘material improvisation’ analogous to John Coltrane’s ‘waves of sound’ (2017: 169).

To create cascades of colours in his work, Gilliam pours paint onto the canvas and then folds the canvas repeatedly, applying more paint as he proceeds. This introduces chance and contingency into his paintings—characteristics that he emphasizes by draping and hanging his unframed work, making its display ephemeral and non-repeatable. Gilliam’s paintings therefore blur the boundaries between painting, performance, and sculpture.

April 4 addresses, Gilliam writes, ‘the sense of a total presence of the course of man on earth, or man in the world’, (Binstock 2005: 71). Despite its abstraction, the work is unabashedly representational. The circles of red suggest gunshots and blood. The purple background suggests royalty. The colours caught in the folds trace an outline reminiscent of the Shroud of Turin. Dr Martin Luther King Jr.’s death therefore reflects the death of many more African Americans who are unremembered and unmourned, and yet who have been murdered just as unjustly, as if they did not matter.

At the same time, the improvisational quality of April 4 reinforces the fractures found even in memory. How can art archive loss, when what has been lost is not merely an exceptional life, but the larger social vision behind it of integration through love and nonviolence? Without this wider horizon, who are we? What have we become? Gilliam’s painting invites the viewer to lament—to mourn what we have done, and yet to imagine what we might be.

References

Binstock, Jonathan P. 2005. Sam Gilliam: A Retrospective (Berkeley: University of California Press)

Godfrey, Mark. 2017. ‘Notes on Black Abstraction’ in Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, ed. by Mark Godfrey, and Zoé Whitley (London: Tate Publishing)

Alison Saar

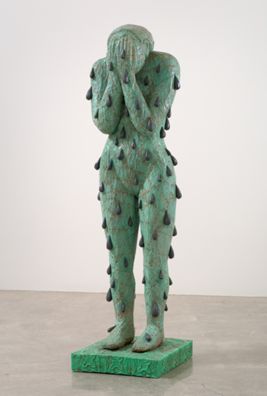

Blood/Sweat/Tears, 2005, Wood, copper, bronze, paint, and tar, 182.9 x 61 x 50.8 cm, Detroit Institute of Arts, Museum; Purchase, W. Hawkins Ferry Fund, 2011.2, © Alison Saar; Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA

The Lamenting Body

Commentary by William J. Danaher, Jr.

The daughter of Betye Saar, a seminal African-American artist, and Richard Saar, a ceramicist and conservator who was white, Saar describes herself ‘floating between two worlds’ (Dallow 2005: 27). Following her mother, Saar creates from reclaimed material. In the case of Blood/Sweat/Tears, these are beams of lumber that she carves with a chain saw, ceiling tin that she moulds into a base, copper strips that she nails to the wooden core, and droplets made of cast bronze. Saar also draws upon African rituals and mythology to create critical intersections between spirituality, ancestry, and identity. Following her father, Saar employs European sculptural disciplines and appropriates the European mythic canon, in particular Persephone and Demeter, goddesses cursed to grieve periodically for eternity.

This double-lineage is evident in Blood/Sweat/Tears, which achieves two complementary purposes. The first is to ‘make visible black women’s historical struggle to reclaim their own bodies, turning themselves from exoticized objects into critical subjects’ (Dallow 2004: 93). Rather than an object of projection, Saar’s grieving figure claims the viewer’s attention. This body language upsets the normative gaze, which has long eroticized African-American bodies. Rather than Eros, one sees Thanatos, as well as a deeper transition from death to life.

The second is the ‘historical role of the body as a marker of identity, and the body’s connection to contemporary identity politics’ (Dallow 2004: 93). Saar’s use of reclaimed materials reminds us that our bodies carry within them ‘the former lives’ and ‘histories of what they have witnessed’ (Lux 2011). Thereby, Blood/Sweat/Tears communicates the layered complexity of her grief—the personal grief she bears over losing her father as well as the political grief she feels as a biracial woman living in a culture that routinely ignores and denies the suffering bodies of African Americans. Lamentation, her work suggests, is not the exception but the norm, and, ironically, the bridge between the two worlds she inhabits.

References

Dallow, Jessica. 2004. ‘Reclaiming Histories: Betye and Alison Saar, Feminism, and the Representation of Black Womanhood’, Feminist Studies 30(1): 74–113

———. 2005. ‘The Art of Creating a Legacy’, in Family Legacies: The Art of Betye, Lezley, and Alison Saar, ed. by Jessica Dallow, and Barbara C. Matilsky (Seattle: University of Washington Press)

Lux Art Institute. 2011. ‘Artist-in-Residence: Alison Saar’, www.luxartinstitute.org [accessed 20 October 2018]

Ana Mendieta :

Imagen de Yagul, from the series Silueta Works in Mexico 1973–1977, 1973 , Chromogenic print

Sam Gilliam :

April 4, 1969 , Acrylic on canvas

Alison Saar :

Blood/Sweat/Tears, 2005 , Wood, copper, bronze, paint, and tar

Archiving Lament

Comparative commentary by William J. Danaher, Jr.

Laments express sorrow, anger, and frustration in the wake of catastrophe. Weaving together themes of loss, suffering, memory, vengeance, forgiveness, hope, and healing, laments perform a fractured identity. Vacillating between what is said and unsaid, between speech and silence, laments inhabit the shifting space between ritual, text, and performance.

A lament, as James Wilce notes, is a public performance improvised in real time as ‘melodic weeping with words’ (2009: 33). By contrast, our memories of lament are privately composed and presented as a finished product. This leaves a gap between the performance and the tradition, text or images that remember and interpret a lament. Every lament bears a unique set of features—words, sounds, smells, gesture, dance, music, setting, history, etc. However, to transcend this context, a lament must be transposed into a coherent and repeatable ‘set of signs’. Each additional performance adds to this entextualization, since ‘performance is entextualization’ by restructuring the lament so that it becomes memorable (Wilce 2009: 33).

Laments express what Richard Schechner calls ‘restored behavior’—the redeployment of past ‘strips of behavior’ in the present so that ‘individuals and groups’ can ‘rebecome what they once were’, or even, ‘what they never were but wish to have been or wish to become’ (1985: 37–8). Laments speak with a ‘double-voice’ in a ‘double-time’, thus amplifying the griever’s voice by echoing what has been said in another age (Wilce 2009: 58). This patina of antiquity lends authority. By incorporating inherited grievances into her own performance, the griever’s laments survive.

These dynamics are evident in Lamentations 1 and the artworks selected here. Written in the aftermath of three military assaults that left Jerusalem in ruins and its inhabitants in exile, a narrator compares Jerusalem to a woman who is the victim of violence and exploitation (1:1–11b). The personified city herself interrupts to implore God to ‘see’ (ra'ah) her affliction (1:9, 1:11c–22). As Kathleen O’Connor notes, a gender politics is at play here. The narrator’s ‘dispassionate description’ has ‘provoked’ Jerusalem to speak. She does not ask for ‘the return of her children, for freedom, or for the return of past splendor’. She only ‘wants God to see her pain’, but ‘God does not reply’ (O’Connor 2002: 22).

Standing behind this exchange is a longstanding tradition in antiquity that objectified women as ‘lament-loving’. Women typically played the emotive role of performers; men the intellectual role of archivers. This established, as Wilce notes, an ‘emotional regime’ of reserve that continues today (2009: 62–70). Jerusalem’s persistence therefore resists the ‘domineering logic of the archive’ that would make her performance ‘disappear’ from memory (Blocker 2004: 106). Of course, the actual lament that inspired Jerusalem’s voice goes unrecorded. We can only imagine the pain and horror she experienced. We can only trust God heard and saw her suffering.

Similar tensions exist in Ana Mendieta’s Imagen de Yagul (1973). Lying, as if dead, in the ruins of a Zapotec tomb, the flowers covering her body refer to both a common mourning practice and a deeper process of death and resurrection. Like other works from her series Silueta Works in Mexico 1973-1977, Mendieta is both the performer and archivist of this intersectional work, thus upsetting the usual gender politics of lament.

Alison Saar’s Blood/Sweat/Tears (2005) is a life-sized statue of a naked, grieving figure clothed in bronze droplets representing either blood, sweat, or tears. Highlighting the struggles of African-American women, Saar draws from African indigenous art and from the myth of Persephone and Demeter, goddesses who are cursed to grieve periodically for eternity. This statue also remembers the death of her father, Richard. She thus highlights the ‘double-voice’ and ‘double time’ features of lament.

Sam Gilliam’s April 4 (1969) remembers the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King, Jr. Gilliam pours colours on a canvas that he folds repeatedly before hanging it loosely on a wall. The circles of red suggest gunshots and blood. The purple background suggests royalty. The colours caught in the folds trace an outline that is reminiscent of the Shroud of Turin. Nonetheless, the work’s abstraction destabilizes the archiving process. Despite its resilient beauty, King’s memory must be recreated in our minds to understand the work’s message. We are thus invited to perform our own lament from the loosely constructed archive Gilliam creates, to imagine what we wish to have been or wish to become.

References

Blocker, Jane. 2004. What the Body Cost: Desire, History, and Performance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press)

O’Connor, Kathleen M. 2002. Lamentations and the Tears of the World (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books)

Schechner, Richard. 1985. Between Theater and Anthropology (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press)

Wilce, James M. 2009. Crying Shame: Metaculture, Modernity, and the Exaggerated Death of Lament (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell)

Commentaries by William J. Danaher, Jr.