2 Samuel 13

Tamar and Amnon

Bernardo Cavallino

The Murder of Amnon by his brother Absalom, 17th century, Oil on canvas, 103 x 133 cm, Private Collection; Private Collection / Bridgeman Images

Sexually Transmitted Disease

Commentary by Ellen T. Charry

More fish than Amnon sputter on the author’s grill. The rape of Tamar appears in the narrative immediately after Nathan’s double rebuke of David. David is condemned for adultery (perhaps also rape, although the text is silent about whether Bathsheba spared her own life by not resisting; 2 Samuel 11:4). And he is condemned for assassination (2 Samuel 11:15–17).

Some of David’s sons followed their father’s path. If the taking of Bathsheba reveals David’s moral illness and the rape of Tamar reveals Amnon’s moral illness, the assassination of Amnon is about Absalom’s moral turpitude.

After Amnon’s rape of Tamar, David refuses to punish his heir apparent. But Absalom, David’s third son and Tamar’s full brother, sees an opportunity. He begins to plot against Amnon (ostensibly in retaliation for the rape), and therefore also against David. He arranges a banquet where he has Amnon assassinated (2 Samuel 13:28–29). Slier and more ambitious than Amnon, he takes out his rival for the throne.

Bernardo Cavallino’s painting of this assassination is telling. The hit man, accoutred in medieval armour, has his face illuminated—by contrast with the host, the real assassin. The victim is seated at the head table across from the shady Absalom. It is Absalom’s long index finger, not his face, that catches the light as he points at his brother.

The mercenary surprises Amnon from behind, pulling him back by the hair (in what might be a wry anticipation of Absalom’s own future death, caught by his hair in the branches of a tree; 2 Samuel 18:9–15). He reaches for the weapon with which he will turn a convivial feast into the scene of a homicide.

Thus the fratricidal Absalom (the name means ‘father of peace’!) uses his disgraced sister to advance his dynastic aspirations. Perhaps the various additional figures in attendance here include some of David’s other sons (we know of twenty-one by eighteen women, at least two of whom died in infancy). Their consternation is understandable.

Amnon is a manipulative liar and rapist. Absalom is an equally manipulative liar and murderer. Their father is a recognized adulterer and assassin. David’s monarchy cracks under its own weight.

Jan Steen

Amnon and Thamar, c.1661–70, Oil on oak panel, 67 x 83 cm, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud; Acquired in 1936 as part of the Carstanjen collection, WRM 2536, © Rheinisches Bildarchiv, rba_c010936

Testosterone’s Toy

Commentary by Ellen T. Charry

Rape is a vile wrong in ancient Israel. In a society that lacked the rule of law, it prompts revenge killing through war in one instance and civil war in two other cases.

The rape of Dinah (Genesis 34) led to war against the Shechemites. The gang rape and slaughter of a wife of a Levite (Judges 19) ended in a protracted and vicious civil war. The duplicitous rape of Tamar by her half-brother Amnon, both children of King David (2 Samuel 13), also led to civil war. Sexual incontinence becomes an excuse for self-serving political ends. Women are both abused (by our standard) and instrumentalized.

Rape is about the instability of male sexuality unleashed by unbridled testosterone. It is about female vulnerability to male physical strength and sexual lust. Male sexual instability concerned the biblical authors. Yet, these rape stories are about more than male self-indulgence. In the case of Amnon, the instability of male sexual lust is shown to go far beyond the gross violation of a woman’s mind and body. It is pernicious socially, politically, and religiously.

Amnon’s rape of Tamar, abetted by David and secured by lying to his comely half-sister, discloses this instability. Having gratified himself momentarily he reveals himself further by turning on his victim. His hatred of Tamar is interpretable as self-hatred at his own weakness projected onto her. She begs him to marry her to restore her place in society when women were believed to be dishonoured by rape. He retorts, ‘Get out of here’ (2 Samuel 13:15 own translation). She continues to beseech him but he orders his servant: ‘Get this thing out of here and bolt the door behind her’ (2 Samuel 13:17 own translation).

The biblical author’s blatant moral point about Amnon seems lost on the seventeenth-century Dutch painter Jan Steen. He insensitively depicts the servant as mocking the incident, distracting our attention from the unstable predator with a vaudeville comedy act. Sex is male amusement. Women are toys to Amnon and perhaps also to Steen.

Yet as bawdy as Steen’s painting is, there may be an element of truth here that women disregard at their peril.

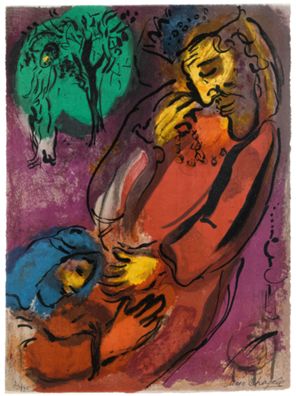

Marc Chagall

David and Absalom (from 'The Bible'), 1956, Colour lithograph, 355 x 265 mm, Private Collection; © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris; Photograph courtesy of Sotheby’s

Blood Stains

Commentary by Ellen T. Charry

Marc Chagall carries the story that began with Tamar’s rape in 2 Samuel 13 through to 2 Samuel 18, near the end of the David stories.

The lithograph elides more than one moment in David’s struggle with Absalom. In the lower right, we see Absalom begging for forgiveness from his father years after the murder of Amnon (2 Samuel 14:33); in the upper left, we see Absalom’s assassination by Joab, David’s general. While directing the campaign against Absalom, Joab disobeys David’s order to spare his son and murders him (2 Samuel 18:1–15); David then mourns the death of his rebellious and vicious son (2 Samuel 18:24–33). Absalom’s years of plotting to overthrow his father culminate in total defeat.

Perhaps Chagall chose red for David’s garment—the colour of blood—to call to mind God’s refusal of one of David’s cherished hopes: to build God’s house in Jerusalem in an act that would affirm his victory over the Jebusites. Once David settled in as king of Israel, and long before the confrontation between them, he sought the prophet Nathan’s advice about building God’s house in Jerusalem (2 Samuel 7). Nathan initially encouraged David but with dripping irony the biblical author adumbrates what is to transpire in later history. God tells Nathan to tell David that his son, not David, will have that honour. But he does not say why.

The later-dated text of 1 Chronicles fills in the information by putting the words in David’s own mouth: ‘God said to me, “You may not build a house for my name, for you are a warrior and have shed blood”’ (1 Chronicles 28:3).

One wonders whether Chagall’s opulent use of red recalls these biblical counsels. The honour is bestowed upon Solomon who uses foreign policy (through marriage) rather than military might to forward Israel’s empire (1 Kings 11:1). Solomon is stained by idolatry (1 Kings 11:5), but David’s whole body is blood-stained and it spills over onto his son. The blood spilled in war mingles with the blood of violated women like Tamar and the blood of family vendettas. All pass judgement on David and his house.

This is perhaps what Chagall notes (astutely if so) by bleeding David’s red onto Absalom’s beseeching hand and coat.

Bernardo Cavallino :

The Murder of Amnon by his brother Absalom, 17th century , Oil on canvas

Jan Steen :

Amnon and Thamar, c.1661–70 , Oil on oak panel

Marc Chagall :

David and Absalom (from 'The Bible'), 1956 , Colour lithograph

The Poison of Power

Comparative commentary by Ellen T. Charry

Disclosure of male sexual lust points toward the lust for power that suffuses the House of David originally blessed by God (2 Samuel 7).

Samuel’s warning against monarchy (1 Samuel 8:10–22) hovers over both biblical books that carry his name. He objected strenuously when the Israelites first begged for a king as other nations had. The self-destructive poison of power yields the desecration of women, fratricide, war, civil war, societal instability. Samuel weeps in his grave.

Of our three artists, two seem to have got the biblical author’s point, while Jan Steen seems to miss it, at least on first reflection.

Bernardo Cavallino and Marc Chagall understand that the evil actors, Amnon and Absalom, are the chief subjects of the stories while Steen seems caught up in his cultural location—one that was closely connected with the theatre. His training taught him to paint exaggerated figures as if the characters were stage actors. His painting is as much about the fool as it is about the debased rapist or the violated woman.

But from ancient times up to our own day, innocent rape victims are often shamed although they are guiltless, and even in some cases considered accomplices to what the rule of law knows to be a crime against them. In rape as in slavery (they often go together), it is the victim’s dignity that is lost, not that of the perpetrator.

These three art works, hovering around the rape of Tamar (prepared for by David’s crimes of adultery and murder, and their aftermath) reveal much about ancient Israel’s sordid leadership. Fortunately, it was carefully preserved for our edification by the Deuteronomist as a great red flag. The author(s) of the Deuteronomic history, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings, tell an extended morality tale that every age can understand. And this narrative inexorably points to us, just as the author hoped.

The Deuteronomist knows that power corrupts weak spirits. He is direct. Our painters, along with other interpreters of the text, wend their way between the morally astute biblical authors on one side and their immediate audiences on the other—finding bridging points between the two.

These texts need no help from modernizers. In 2 Samuel 13–18 we enter the entrails of human ignominy. Judaism’s rabbinic sages noted that trespass breeds trespass (Pirkei Avot 4:2); the biblical authors got it.

Steen contemporizes the rape of Tamar for his effete seventeenth-century audience dwelling in opulent theatrical foppery. He seems to have reinforced the misogyny of the biblical story. Though this may cause us to raise our eyebrows in shock some four centuries later, it is possible that he hoped to engender a sense of arch collusion among his original viewers.

For his part, Cavallino exposes the ugly lust for power that abides in the human breast. What could speak more directly to our own moment? Intrigue, scheming, lying, back-biting, betrayal, self-advancement, flaunting, selling one’s integrity, manipulating others for personal political and ultimately financial and corporate advancement—all this leers at us. So does the politicization of our base taste for revenge, dressed up as righteous anger. Self-gain clothed as retribution is an apt motif for many political moves in our present day.

The West inherited religion from the ancient Israelites and many aspects of the rule of law from the ancient Romans. The West is now struggling to hold onto both.

At least two of our artists appear to have selected biblical texts in order to edify their audiences. Today Cavallino might be identified as a peace activist using art to highlight the ugliness of human ambition dressed in royal garb. Chagall, whose work presses deeply into the biblical stories, takes us inside the mind and heart of one of ancient Israel’s most complex and vaunted characters. David is an outsized figure both in the Hebrew Bible, where he figures in his own right, and in the Younger Testament where he authenticates Jesus’s pedigree (Matthew 1). Some may object that the biblical characters are not legitimated beyond the biblical text but the blood-stained life of this dashing yet ugly powerhouse would be difficult to invent. David is complex enough to be real.

But Tamar may not be eclipsed, for she has every bit as much to teach.

Art does theology in many of the ways that other genres do. It has the advantage of being immediately accessible to wider audiences than the written word. It speaks in every age. Despite the profound moral flaws of Steen’s interpretation of Tamar’s story, he at least acknowledges the fact that a woman is ineradicably at the heart of this tale.

The story of male power interpreted here by three male artists is truly told only with her help.

Commentaries by Ellen T. Charry