Ruth 1

An Uncertain Future

John Warrington Wood

Ruth and Naomi, 1884, Marble, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool; Purchased from the artist's sister, Mrs Mary Darbyshire, by the Walker Art Gallery, 1902, WAG 4109, National Museums Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery / Bridgeman Images

Choices

Commentary by Heather Macumber

British sculptor John Warrington Wood captures the celebrated moment in which Ruth clings to Naomi and begs permission to accompany her to Bethlehem (Ruth 1:16). This passionate speech, memorialized in many modern wedding readings, highlights the faithfulness of Ruth.

While the sculpture communicates Ruth’s devotion, it also raises questions regarding Naomi’s ambivalent reaction and desires. Scholars have proposed that Naomi is less than enthused about the presence of Ruth, who is both a foreigner and potentially a burden as a fellow widow (Fewell and Gunn 1999: 236; Sakenfeld 1999: 34–35). This ambiguity is discernible in the sculpture, as the women’s embrace is not portrayed as entirely reciprocal. Ruth’s arms are draped over her mother-in-law with her face upraised in supplication. In contrast, though Naomi’s face is bent towards the younger woman, she does not return the intensity of Ruth’s hold. Naomi’s left hand rests lightly on Ruth’s lower back, while her right one gathers her garment as she steps forward. A long journey awaits Naomi, and her posture indicates her determination to return home.

Ruth’s name precedes that of Naomi in the title of the sculpture; however, Warrington Wood does not treat Naomi as a supporting character. While the naming of the biblical book after a single character might predispose one to privilege Ruth’s story, Naomi’s journey holds equal importance for the narrator. In the book of Ruth’s first chapter, Ruth’s eloquent words of devotion to Naomi are remembered and revered, yet they are mirrored by Naomi’s lesser-known lament regarding her bitter condition (Ruth 1:20–21). There is an unresolved tension as the women move towards Bethlehem that culminates in Naomi’s angry pronouncement that she has adopted the name Mara meaning ‘bitterness’ (Koosed 2011:62). The chapter ends with Naomi’s experience of emptiness, a lack of blessing that she attributes to her God.

References

Fewell, Danna Nowell and David Miller Gunn. 1999. ‘“A Son is Born to Naomi!”: Literary Allusions and Interpretation in the Book of Ruth’, in Women in the Hebrew Bible: A Reader, ed. by Alice Bach (New York: Routledge), pp. 233–39

Koosed, Jennifer L. 2011. Gleaning Ruth: A Biblical Heroine and her Afterlives (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press)

Sakenfeld, Katharine Doob. 1999. Ruth, Interpretation (Louisville: John Knox)

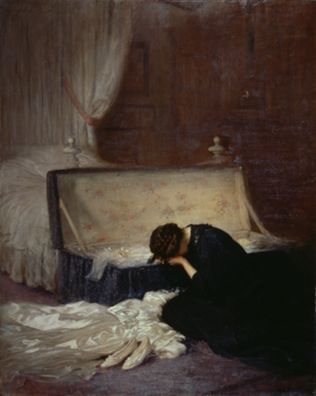

Frederick W. Elwell

The Wedding Dress, 1911, Oil on canvas, 128 x 103 cm, Ferens Art Gallery, Kingston Upon Hull; Gift, 1914, KINCM:2005.4894, ©️ Ferens Art Gallery / ©️ Estate of Frederick Elwell. All rights reserved 2024 / Bridgeman Images

Grief

Commentary by Heather Macumber

Frederick Elwell’s The Wedding Dress juxtaposes light and shadow, pointing up the disparity between life and death, hope and despair.

A white wedding dress and shoes lying on the floor draw one’s attention to the figure of a grieving woman dressed in dark clothes. With her face buried in her hands, she is bent over a chest from which the edge of a bridal veil spills out. Shadows dominate the muted, panelled bedroom walls in the background while at bottom right they merge with the wedding chest and the woman’s clothes. There is a haunting quality to the painting as it highlights the absence or trace of something that cannot be retrieved.

Elwell was known for his other works centred on domestic subjects, particularly The First Born (1913) where a father leans over to view his wife and newborn child. Bright tones dominate that painting in stark contrast to The Wedding Dress where the domestic setting no longer harbours life but death.

The identity of the grieving woman in The Wedding Dress is unknown. She may be a widow, or a prospective bride who has lost her fiancé. The wedding chest, a symbol of hope for one’s future, takes on a more ominous tone as it bears an uncanny resemblance to a funeral casket.

The book of Ruth also opens with the intersection of familial hope and despair. It is a domestic tale focused on the daily lives of a single Israelite family. Naomi with her husband and her sons seek refuge in Moab from a famine in Bethlehem. Although known as ‘the house of bread [or 'food']', here is a terrible and ironic reversal for this family as Bethlehem becomes a place of scarcity.

More reversals follow. Their initial security in Moab is upended by the death of Naomi’s husband and two sons. Both Naomi and her daughters-in-law Ruth and Orpah are widows, left childless after the passing of their husbands. With no explanation for the death of the men, the book of Ruth, like Elwell’s The Wedding Dress, leaves the audience to fill in the gaps.

Yet, though this chapter opens with famine and despair, the narrator anticipates a hopeful change to their situation as Naomi and Ruth return to Bethlehem at the beginning of the barley harvest (Ruth 1:22).

Marc Chagall

Naomi and her daughters-in-law, 1960, Lithograph, 525 x 380 mm, Musée National Marc Chagall, Nice; MBMC429, ©️ RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Solace

Commentary by Heather Macumber

This sepia-toned lithograph is one of five scenes from the book of Ruth featured in Marc Chagall’s Drawings for the Bible. A similar colour scheme of muted browns and reds marks Chagall’s treatment of other episodes from the book, which were first published by Verve in 1960.

The vegetation in the background along with the unidentified animal in the foreground potentially allude to the security found in Moab compared with the famine left behind in Bethlehem. In the upper right corner, the hot red sun stands out prominently by contrast with the subdued tones of the composition. Conversely, the lack of any building in the background which might be their home may indicate that this is a wilderness location, and that they have already begun their difficult journey from Moab to Bethlehem (Ruth 1:6–7).

It is noteworthy that Chagall positions all three women centrally—merged in an emotional embrace—rather than simply focusing on Ruth and Naomi. This posture is reminiscent of the iconography of the Three Graces (a famous example being Antonio Canova’s 1814 sculpture in which they are likewise mutually entwined). The younger women surround Naomi, actively holding her, while Naomi’s arms are clasped in front of her body. Chagall does not differentiate between Ruth and Orpah, echoing the way that the biblical text initially treats the daughters-in-law as an indistinguishable pair. Both women are united in their desire to journey with Naomi, weeping and raising their voices (Ruth 1:10).

Although some early Jewish and Christian interpreters maligned Orpah’s choice to return to her family of origin, there is no judgement or shame accorded to her in the biblical text as she (unlike Ruth) obeys Naomi her elder (Koosed 2011: 35–36; Lau 2023: 97–98). Laura Donaldson notes that Cherokee women see in Orpah a hopeful figure who by returning to Moab chooses the house of her mother, positively embracing her traditions and ancestors (Donaldson 2006: 167). Similarly, Chagall in his five scenes from the book of Ruth, diverges from other artists by omitting Orpah’s departure and highlighting a moment of intimacy between women struggling with grief and loss (O’Kane 2010: 144).

References

Donaldson, Laura E. 2006. ‘The Sign of Orpah: Reading Ruth through Native Eyes’, in The Postcolonial Biblical Reader, ed. by R.S. Sugirtharajah (Malden: Blackwell Publishing), pp. 159–70

Koosed, Jennifer L. 2011. Gleaning Ruth: A Biblical Heroine and her Afterlives (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press)

Lau, Peter H. W. 2023. The Book of Ruth, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans)

O’Kane, Martin. 2010. ‘The Iconography of the Book of Ruth’, Interpretation, 64.2: 130–45

John Warrington Wood :

Ruth and Naomi, 1884 , Marble

Frederick W. Elwell :

The Wedding Dress, 1911 , Oil on canvas

Marc Chagall :

Naomi and her daughters-in-law, 1960 , Lithograph

An Ambiguous Tale

Comparative commentary by Heather Macumber

Ruth begins with ‘In the days when the judges ruled’, recalling a narrative setting before the time of David. Readers familiar with Judges recognize that this period of Israel’s history was marked by violence and uncertainty, especially for women (Judges 19–21). Though written in the post-exilic period, Ruth is set within this troubled past, focusing on a tale of three vulnerable women. Whether through death or migration, Naomi, Ruth, and Orpah are left untethered from societal structures.

The narrator provides little backstory for the book’s characters. Naomi’s husband Elimelech appears briefly in the text before he dies in Moab, and the reader is left in the dark as to the cause of his death or any details to flesh out his character. Even Naomi’s sons Mahlon and Chilion are treated as a homogenous unit without any depth, and the reader is unaware until the end of Ruth to whom they are married. A similar ambiguity extends to Ruth and Orpah, both Moabite women, as readers are given little background regarding their families, traditions, and experiences. Finally, Naomi remains an enigma in respect of her character and motivations, despite her speeches in chapter one. Traditionally, it is assumed that the devotion of Ruth is reciprocated by Naomi, but her unsettling silence after Ruth’s speech leaves this open to question (Ruth 1:18).

The Wedding Dress prompts a similar exercise in interpretation since nothing is known of the context of this weeping woman. Though one might assume the missing subject is a husband or a fiancé, it is also possible that the woman in the painting is a mother, daughter, or sister grieving the loss of a bride who will never wear her wedding dress. A poignant quality pervades the scene as the focus is on the woman left behind rather than the identity of the one she has lost. Moreover, it is easy to sentimentalize the woman in the painting, but (as in the book of Ruth) the real cause of her grief might be a lack or loss of material security rather than romantic heartbreak.

Marc Chagall’s lithograph stands out for the unity apparent between the three women; their bond is tangible as they are linked together both physically and by shared trauma. Phyllis Trible notes this cohesion in the biblical text, ‘as childless widows, these three are one’ (Trible 1978: 169). Their loyalty is also reflected in Orpah and Ruth’s textual refusal to leave Naomi, ‘Surely with you, we will return to your people’ (Ruth 1:10). Despite differences in age and ethnicity, Naomi and her daughters-in-law find their narratives intertwined as they grapple with the sorrow of the past and the uncertainty of the future.

Each woman has crossed borders, merging her identity with another culture. This entails, for Naomi, settling in Moab for over ten years, while Ruth and Orpah must adapt to living with an Israelite family as Moabite women. Though some commentators note the bias against Moabites elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, such an overt negative evaluation is missing from Ruth (Koosed 2011: 32).

The beginning of Ruth is marked by famine, while the end of the chapter coincides with the barley harvest, and each woman is similarly transformed throughout the course of the narrative (Linafelt 1999: 18). Though Naomi returns to her homeland with Ruth, she comes back in much-reduced circumstances, forced to glean for subsistence. This fleeting moment of unity captured by Chagall is bittersweet as the family once again faces separation and loss.

Absence is inscribed upon the book of Ruth, from the loss of a homeland, the death of family, and the geographical separation of loved ones. John Warrington Wood’s sculpture Ruth and Naomi highlights the intimate relationship between these two women; however, the absence of other characters is palpable. Most notably, Warrington Wood omits Orpah from his representation, and introduces a level of ambivalence in Naomi’s half-hearted return of Ruth’s embrace. She is already moving away from the younger woman as she prepares to leave for Bethlehem. The indecipherability of Naomi’s attitude is similarly present in the biblical text where Naomi responds to the townswomen, ‘I went away full, but the Lord has brought me back empty’ (Ruth 1:21a). Naomi’s words seem particularly harsh considering the presence of Ruth at her side during this declaration, leaving the reader to wonder whether Ruth is seen as a blessing or a burden.

The book of Ruth is less a quaint love story than an ambiguous text that resists precise meaning (Linafelt 1999: 8). There are more gaps than explanations in the stories of the characters, leaving much to the imagination of the reader. Not only do the spectres of Elimelech, Mahlon, and Chilion hover at the edges of the text, but the eventual fates of Orpah, Naomi, and Ruth are never fully resolved.

References

Koosed, Jennifer L. 2011. Gleaning Ruth: A Biblical Heroine and her Afterlives (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press)

Linafelt, Tod. 1999. Ruth and Esther, Berit Olam: Studies in Hebrew Narrative and Poetry, XXV; XXII (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press), pp. xiii–87

Trible, Phyllis. 1978. The Rhetoric of Sexuality (Philadelphia: Fortress Press)

Commentaries by Heather Macumber