1 Peter 1:1–12

Where Angels Long to Look

Pat Steir

Waterfall of the Misty Dawn, 1990, Oil on canvas, 198.1 x 314.9 cm, Private Collection; Courtesy of Pat Steir and Lévy Gorvy

Ready to Be Revealed

Commentary by Rebekah Eklund

In 1 Peter’s first chapter, his recipients are in motion. They are being protected; they are receiving (1 Peter 1:5, 9).

American painter Pat Steir’s Waterfall of the Misty Dawn is not a painting of 1 Peter. It’s not about the epistle or the apostle. But when set alongside the biblical text, it illuminates Peter’s words, inviting us to consider them in a new way.

Steir (b.1940) uses techniques whose names evoke the fluidity of a waterfall: ink-splashing or flung ink (common in Chinese landscape painting), and drip painting, which creates the long, thin vertical lines of paint streaming down the canvas. The suggestion of incessant motion in Steir’s Waterfall can highlight the motion of Peter’s recipients, too. They’re journeying towards their inheritance—imperishable, unfading—which is being kept in the heavenly realm for them. It’s an inheritance that they have to die (and rise) in order to receive.

The very elusiveness of the connections between Peter’s missive and Steir’s waterfall tugs at another important thread of 1 Peter’s first chapter: the theme of seeing and not seeing, of believing while straining forward to see something that has not yet appeared (1 Peter 1:8). The joyful news of their salvation is a mystery long hidden and now revealed. The word ‘revealed’ (Greek apokalyptō and apokalypsis) is repeated three times in these twelve verses. Angels long to see into such things! But even they couldn’t see past the veil.

When one gazes at Steir’s waterfall, one’s eyes are drawn not only to the streams of water but also to what lies behind the shimmering veil. The ‘misty dawn’ in the painting’s title evokes the unfading inheritance that Peter’s recipients are waiting to receive (1 Peter 1:4). The dawn has long been used by Christians to symbolize the arrival of God’s new age—as when Luke’s Gospel describes Jesus’s birth as ‘the dawn from on high’ breaking upon Israel (Luke 1:78), and when Christ is given the title the ‘Dayspring’ (an older word for the dawn). Jesus’s dawning is their living hope, the glory they rejoice in even before they can see it (1 Peter 1:3, 8).

References

Denson, G. Roger. 1999. ‘Watercourse Way’, Art in America, 87.11: 114–21

McEvilley, Thomas. 1995. Pat Steir (New York: Harry N. Abrams)

Olga de Amaral

Alchemy 50 (Alquimia 50), 1987, Canvas, gesso, gold leaf, and acrylic paint, 165 x 150 cm, Tate; Presented by the artist 2016, T14879, © Olga de Amaral; Photo: © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

The Alchemy of Faith

Commentary by Rebekah Eklund

At first glance, this intricate weaving has no obvious link to a biblical letter about suffering and salvation. Yet its very title invites a closer look.

This work is part of the Alchemies (Alquimias) series created by Colombian artist Olga de Amaral (b.1932). The ancient practice of alchemy had several aims, but its most famous was the quest to turn lead (or other base metals) into gold. The artist has used actual gold—delicate, thin strips of gold leaf—to create her textured piece.

As a symbol, gold is multifaceted; it is widely seen as the most precious of metals and is admired or coveted for its beauty. The use of gold establishes a connection between the ancestral culture of Colombia’s precolonial past and the later adornment of Christian churches after Catholicism arrived with fourteenth-century Spanish colonialists. In some cultures, it is a symbol of immortality; in others, of knowledge. The term ‘golden age’ (derived from Greek mythology) is often used to describe a period of exceptional flourishing or achievement. De Amaral (2003) herself has noted the association of gold with knowledge.

Peter appeals to another common quality of gold in his letter: its ability to be refined through fire (1 Peter 1:7). Because gold has a low melting point, it can be stripped of impurities or other metals in a hot fire. Peter reminds the suffering Christians who receive his letter that their faith is like gold, and their suffering is like a fire. They are being refined through fire, and their faith will be stronger and more genuine because of their suffering. But their faith is unlike gold in another way: gold, although beautiful and long-lasting, is not immortal. It is—ultimately—perishable. Their faith—and the inheritance that awaits them—is, by contrast, imperishable and unfading. Nothing can defile or destroy it.

Of course, De Amaral’s work is not simply a sheet of gold. It is interwoven with small black threads. The gold shimmers behind a veil, indistinct, not fully visible. Likewise, Peter urges the hearers of his letter to rejoice in things they have not yet seen (1 Peter 1:5, 8), to prepare for the divine ‘alchemy’ that will transform their mortal bodies into glorious and imperishable ones (1 Corinthians 15:42–54).

References

De Amaral, Olga. 2003. ‘The House of My Imagination: Lecture by Olga de Amaral at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 24 April 2003’ (Bogotá: Zona)

Goin, Chelsea Miller. 1998. ‘Textile as Metaphor: The Weavings of Olga de Amaral’, in A Woman’s Gaze: Latin American Women Artists, ed. by Marjorie Agosín (Fredonia, NY: White Pine Press), pp. 54–63

Eugène Burnand

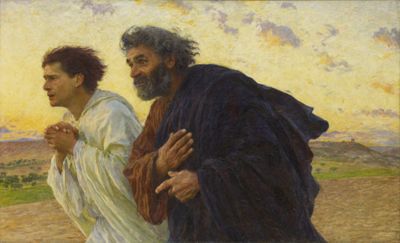

The Disciples Peter and John Run to the Sepulchre the Morning of the Resurrection (Les disciples Pierre et Jean courant au Sépulcre le matin de la Résurrection), 1898, Oil on canvas, 83 x 135.5 cm, Musée d'Orsay, Paris; RF 1153, LUX 1219, JdeP 338, Photo: Martine Beck-Coppola © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Loving Without Seeing

Commentary by Rebekah Eklund

Here the aged letter-writer (Peter) runs alongside his young friend, John son of Zebedee. Those familiar with John’s Gospel will know what directly precedes this moment: another disciple, Mary Magdalene, has just seen the risen Jesus, and has told Peter and John the astonishing news (John 20:1–2). Swiss painter Eugène Burnand (1851–1921) shows the two disciples running to Jesus’s tomb to see for themselves.

Burnand often painted everyday working people, and Peter and John appear not as enhaloed saints but as two fishermen. John clasps his hands in pleading prayer; Peter holds one hand, weathered with age and sun, over his heart, while the other points ahead (is that the tomb in the distance, just out of view?). They hurry forward. One can almost feel the cool morning air on their faces.

Dawn breaks; the sky is flooded with gold. Of course, Burnand paints the dawn because it was still early in the morning when Mary Magdalene discovered the empty tomb. But for Christians the dawn becomes also a symbol of the dawning of God’s new age, when they too will rise and receive the unfading inheritance being kept in heaven for them (1 Peter 1:4).

When Peter writes his letter to the exiles of the Diaspora—that is, to Christians scattered across Asia Minor—he uses gold as an image of their faith (v.7). Just as gold is refined in fire, so their faith was being tested and made stronger by suffering. Peter knew his own suffering, not only as he ran to his Lord’s tomb, hoping against hope that it would be empty as Mary promised, but also in the bitter tears he wept after he denied knowing Jesus three times just before Jesus’s death (John 18:15–18, 25–27).

When Peter wrote, ‘Although you have not seen him, you love him’ (1:8), he might have been describing his own beating heart, and John’s, as they ran on that first Easter morning—not seeing, but still straining forwards.

Pat Steir :

Waterfall of the Misty Dawn, 1990 , Oil on canvas

Olga de Amaral :

Alchemy 50 (Alquimia 50), 1987 , Canvas, gesso, gold leaf, and acrylic paint

Eugène Burnand :

The Disciples Peter and John Run to the Sepulchre the Morning of the Resurrection (Les disciples Pierre et Jean courant au Sépulcre le matin de la Résurrection), 1898 , Oil on canvas

Just Before the Dawn

Comparative commentary by Rebekah Eklund

The opening words of 1 Peter call forth joy at the glorious splendour of God’s salvation. ‘You are rejoicing’, the author twice reminds his hearers (1 Peter 1:6, 8). But they are also suffering.

We don’t know exactly what their ‘various trials’ were (1:6). Peter addresses them as ‘exiles’ living in five provinces of the Roman Empire in Asia Minor (modern-day Türkiye). We know that, although persecutions were scattered and sporadic in the Roman Empire in the second half of the first century, some Christians did lose property, friends, and livelihoods when they turned to Christ. Some died for their faith. It is this faith that Peter explains is being tested and refined by the fire of their suffering. Peter reminds his first hearers that Christ also suffered and then was glorified (1:11). If found to be genuine, their faith—that is, their trust in God, their faithful endurance—will result in their salvation. That makes their faith even more precious than gold.

All three artworks give us a glimpse into Peter’s gold: from the literal use of gold in Alchemy 50 to the glowing light of Eugène Burnand’s sunrise to the barest hint of warm colour in Pat Steir’s waterfall. All three also, in their own way, may help to illuminate the theme of suffering, and the biblical passage’s acute awareness of what is not yet seen. The dominant note in Steir’s painting is not light but darkness, a black backdrop over which shards of light glimmer. Olga de Amaral’s textile also has a dark feature: the black threads that crisscross the gold, in a very literal way marking the precious gold with the sign of the cross (the classic sign of suffering in Christian thought) over and over again.

Burnand has captured the anxiety in the faces of Peter and John as they hurry forward, caught forever in the moment just before they arrive at the empty tomb, just before they see the risen Jesus for themselves. This, of course, is the exact position in which Peter’s readers find themselves: they have not yet seen the risen Jesus, but they believe anyway. Viewed side by side, the long vertical lines of Steir’s painting are matched visually by Alchemy 50’s small vertical lines, created by the black threads and the fringe at the bottom of the textile. Only Peter and John interrupt this vertical alignment by leaning forward, breaking the vertical plane as they strain into the future.

The perpetual motion of both waterfall and the running disciples gestures toward the ongoing work of faith in the midst of suffering; the endurance and the waiting. American painter Steir was influenced by Daoism, not by Christianity. For her, the ceaseless motion of the waterfall is ‘an example of perpetual becoming and falling’ (Denson 1999: 118). Set alongside 1 Peter, however, falling water and racing disciples might remind the viewer of another exhortation to ‘run with perseverance the race that is set before us’ (Hebrews 12:1), just as Peter encourages his readers to endure in their faith until the end.

That there is an end to their striving reminds us of one final element of the passage’s ‘not yet’ quality, which is reflected in the motif of the dawn in two of the paintings (the ‘misty dawn’ in the title of Steir’s painting and the actual dawn breaking in the background of Burnand’s). In the New Testament, the dawn is both the time of day when the women disciples discovered Jesus’s empty tomb, and a symbol of the end of the old age and the beginning of God’s new age. Peter writes that Jesus has not yet been revealed (1 Peter 1:5, 7). The ‘revealing’ of Jesus is the dawn in this second sense: the end of the old age, the world’s long night, and the birth of the new age, sometimes simply called ‘the Day’, when Christ returns in glory (Romans 8:18; 13:12; 2 Thessalonians 1:7; 2 Peter 1:19). It’s the alchemy of resurrection, when mortal human bodies will rise and be transformed into immortal and imperishable bodies.

This is why Peter refers to the recipients of his letter as exiles, or as pilgrims. They are away from their true homeland, but they are on their way home. They yearn in hope for their inheritance, as Israelites in exile once longed for the promised land. That is the mystery—the completion of their salvation—that even the angels long to see.

References

Denson, G. Roger. 1999. ‘Watercourse Way’, Art in America, 87.11: 114–21

Goin, Chelsea Miller. 1998. ‘Textile as Metaphor: The Weavings of Olga de Amaral’, in A Woman’s Gaze: Latin American Women Artists, ed. by Marjorie Agosín (Fredonia, NY: White Pine Press), pp. 54–63

Commentaries by Rebekah Eklund