Acts of the Apostles 9:32–43

Aeneas Healed and Tabitha Raised

Works of art by Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Masaccio, Masolino and Unknown Byzantine Artist

Unknown Byzantine Artist

View of a section of the nave mosaics with scenes from Genesis and stories of Saints Peter and Paul, 12th century, Mosaic, Palatine Chapel, Palermo; Alfredo Dagli Orti / Art Resource, NY

Variations on a Theme

Commentary by Ben Lima

Throughout Luke and Acts, there is a special concern for the affairs of the broader Gentile world, from the appearance of Caesar Augustus at the beginning of Luke, to Paul’s sea voyages to Rome and Malta at the end of Acts.

This cosmopolitan perspective is easy to adopt when admiring the nave of the Cappella Palatina (Palatine Chapel) in the Palace of the Normans in Palermo.

A spectacular painted wood muqarnas ceiling is done in Fatimid Muslim style. Its geometrical designs would be far more typical in a mosque than in a church, making the Cappella Palatina an apt symbol of the hybrid culture of Sicily under the 12th-century Norman dynasty: Norman (Latin), Byzantine (Greek), and Muslim (Arabic). Drawing from North, South, East, and West, Norman Sicily was a cosmopolitan place.

One contemporary sermon, delivered for the Feast of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, praised the Cappella Palatina as a fitting monument, ‘greatest beyond compare, fairest and most magnificent for its newly created beauty, glittering with light … it imitates the sky, when the serene night air shines all around with the choir of stars’ (Duluș 2022).

Taking in all these mosaics at once suggests that, like the individual facets on the muqarnas ceiling above, or like the individual voices within a symphony orchestra, each episode harmonizes with the larger whole, contributing to the deep structure of salvation history. Both in music and in Scripture, a theme can develop each time that it is repeated. The faithful knew that Elijah, Elisha, and Jesus had healed the sick and raised the dead (e.g. Son of the Widow of Zarephath, Son of the woman of Shunem, Son of the Widow of Nain); the stories of Peter echo these accounts in striking ways. Each individual story is a sign that points to Christ’s ultimate, total victory over sickness and death.

In Acts, as the shock waves from Pentecost ripple across the Mediterranean world, there is no geographical or cultural location beyond the reach of the Holy Spirit, the same God who created Adam, Eve, and all their descendants. The theme first played by Elijah, Jesus, and Peter, then replayed for the Norman-Byzantine-Fatimid Sicilians, has continued to sound in Christian testimonies to healings and resuscitations around the globe, even into the present day (Keener 2013: 1713).

‘Aeneas’, says the Venerable Bede, ‘healed by the work and words of the apostles’ signifies the whole of the ‘ailing human race’ (Acts 9.33).

References

Duluș, Mircea G. 2022. ‘Philagathos of Cerami: The Ekphrasis on the Cappella Palatina in Palermo’, in Sources for Byzantine Art History vol. 3: The Visual Culture of Later Byzantium (c.1081–c.1350), ed. by Fotini Spingou (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Keener, Craig S. 2013. Acts: An Exegetical Commentary vol. 2, 3:1–14:28 (Ada, Michigan: Baker Academic)

Martin, Lawrence T. (trans.) 1989. The Venerable Bede: Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications)

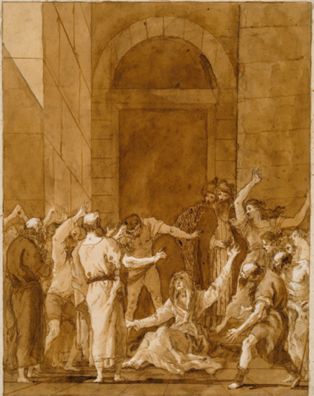

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo

The Raising of Tabitha, Early 1790s, Pen and brown ink with brown wash over charcoal on laid paper, 489 x 381 mm, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; Woodner Collection; Gift of Andrea Woodner, 2006.11.24, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Blessed are the Meek

Commentary by Ben Lima

In Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo’s drawing, the seated Tabitha—an expression of focussed intensity on her face—spreads her arms as if to join in with the circle of friends who surround her. Her right hand appears to meet the edge of Peter’s garment as he stands, his back to the viewer, commanding her to rise. This is artistic licence, since in the text, Tabitha has already been helped up by Peter, before he calls the saints and widows back into the room to see her alive. But Tiepolo's compositional choice both shows the centrality of Tabitha to her people and compresses the drama into a single moment.

Tabitha is one of many important women who appear in Luke and Acts. Here, she is called mathētria (the feminine form of ‘disciple’—appearing only here in the New Testament—while, in contrast, Aeneas was simply a ‘person’, anthrōpon; Acts 9:33). Her good works and acts of charity, making tunics and other garments, have measurably brought grace into the lives of those around her, who now rejoice in her life.

Most of the time, most Christians are more like Tabitha than like Peter, more likely to sew tunics than travel the world preaching. Of Tabitha’s past and present, N. T. Wright affirms, ‘these are the people who form … the beating heart of the people of God’. In Christianity’s transvaluation of pagan values, the meek, such as Tabitha, will inherit the earth, and their lives can become the centre of great celebration.

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo too was a little like Tabitha. Whereas his father Giovanni Battista was renowned for monumental fresco ceilings in the great palaces of Europe and other high-profile decorative works, Domenico had a particular interest in the more intimate medium of drawing. Indeed, for the last 18 years of his life, drawing was his only medium. He spent five of these years working on a New Testament cycle of 313 highly detailed and refined sheets—apparently not for patronage or prestige, or to develop into a final ‘finished’ work in another form, but as an expression of his own piety (Gealt & Knox 2006).

Unlike monumental fresco cycles, drawings are more at home in private collections and among small groups of viewers. In this drawing, Tiepolo depicts just such a small group of people, rejoicing at Tabitha’s return to life. This is what it looks like when the meek inherit the earth.

References

Gealt, Adelheid M. and George Knox. 2006. Domenico Tiepolo: A New Testament (Bloomington: Indiana University Press)

Wright, N. T. 2008. Acts for Everyone, Part 1: Chapters 1–12 (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press)

Masolino and Masaccio

The Resurrection of Tabitha and Peter and John the Healing of the Lame Man, c.1425, Fresco, 255 x 598 cm, Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence; akg-images / Rabatti & Domingie

Mightier than Trajan

Commentary by Ben Lima

In this section of Masolino and Masaccio’s fresco cycle, the two successive episodes of St Peter healing Aeneas and raising Tabitha are shown in a continuous narrative, within a single, unified space. This spatial unity is established by the convergence of all its architectural lines at a single vanishing point. The frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel were among the very first uses of single-point perspective, at that time a brand-new technique being developed in Florence.

Along with spatial unity, these scenes and their neighbouring frescoes also evoke the unity of the church, of which Peter was a symbol, as first among the apostles and, by tradition, first bishop of Rome.

Commenting on the text that introduces the stories of Aeneas and Tabitha (‘Peter passed through all quarters’; Acts 9:32), John Chrysostom figures this unity in military terms: ‘Like the commander of an army, he went about, inspecting the ranks, what part was compact, what in good order, what needed his presence’ (‘Homily 21, Acts 9.26,27’). Indeed, the two renderings of Peter here show him as the personification of decisive, active, forceful leadership, standing tall and strong. Continuous narrative had been used throughout the ancient world to tell the triumphant deeds of great generals (as in Trajan’s Column in Rome, completed a few decades after Peter’s death). Here, the continuous narrative shows the archetypal Christian ‘general’ tending the poor and the sick, and meeting his death on a cross. In this particular episode, the paralyzed man, Aeneas, happens to share his name with the legendary progenitor of the Romans, but his healing points to a new and different kind of universal empire.

The church’s unity is expressed through acts of mercy, which are occasioned by suffering, as Christians share each other’s burdens through care and prayer. Chrysostom observes, ‘Affliction … rivets our souls together’ (‘Homily 21, Acts 9.26,27’).

But affliction is not the end of the story. Citing as support the dry bones who hear the voice of the Lord (Ezekiel 37:4) and Jesus’s prophecy that the dead will hear the voice of the Lord (John 5:25), Calvin states, ‘[t]he voice of Christ…uttered by the mouth of Peter … gave [back] breath to the body of Tabitha’ (Acts 9.40).

It is in Spirit-filled response to this voice that the Church’s unity consists, and that it receives the power to do works mightier than Trajan.

References

Beveridge, Henry (ed.), Christopher Fetherstone (trans.). 1844 [1585]. John Calvin: Commentary upon the Acts of the Apostles, vol. 1, (Edinburgh: Calvin Translation Society)

Eckstein, Nicholas A. 2005. ‘The Widows’ Might: Women’s Identity and Devotion in the Brancacci Chapel’, Oxford Art Journal 28.1: 99–118

Howard, Peter. 2007. ‘“The Womb of Memory”: Carmelite Liturgy and the Frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel’, in The Brancacci Chapel: Form, Function and Setting, ed. By Nicholas Eckstein (Florence: Leo Olschki Editore), pp. 177–206

Walker, J. et al (trans.). 1889. Saint Chrysostom: Homilies on the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistle to the Romans, trans., rev. by George B. Stevens, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, series 1, vol. 11. ed. by Philip Schaff. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans)

Unknown Byzantine Artist :

View of a section of the nave mosaics with scenes from Genesis and stories of Saints Peter and Paul, 12th century , Mosaic

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo :

The Raising of Tabitha, Early 1790s , Pen and brown ink with brown wash over charcoal on laid paper

Masolino and Masaccio :

The Resurrection of Tabitha and Peter and John the Healing of the Lame Man, c.1425 , Fresco

Making Disciples of All Nations

Comparative commentary by Ben Lima

Throughout the book of Acts, as the apostles’ mission expands continuously outwards from Jerusalem towards the outer limits of their known world, two climactic points on the trajectory stand out. First, Saul the persecutor is converted on the road to Damascus, at the beginning of Acts 9. Second, Peter’s vision of the sheet with animals convinces him to preach and offer baptism to the Roman Cornelius and his household: ‘You yourselves know how unlawful it is for a Jew to associate with or to visit any one of another nation; but God has shown me that I should not call any man common or unclean’ (Acts 10:28).

The healing of Aeneas and the raising of Tabitha take place exactly in between these two climactic points. They remind the reader that the dramatic visions which turn Saul (later Paul) and Peter toward the Gentiles do not come from nowhere, but rather fulfil the promises to the Gentiles that can be found throughout the Old Testament. From the rainbow as the sign of the covenant between God and ‘all flesh that is upon the earth’ (Genesis 9:17), to the prophecies directed toward ‘all nations’ in Isaiah and the other prophets, the Abrahamic covenant with the Jewish people has always been part of a larger plan.

Aeneas’s home of Lydda, and Tabitha’s home of Joppa, were mixed between Jews and Gentiles. On the coastal highway running north and south between Caesarea and Egypt, they were busy with trade from all points, much like Norman Sicily, Renaissance Florence, and Rococo Venice. Jonah boarded a ship leaving Joppa for Tarshish (Jonah 1:3), and other ships arrived in Joppa bearing cedars from Lebanon to build the Second Temple (Ezra 3:7).

In this passage, even before Peter has his vision of the animals in the following chapter, there are already signs that Christ through the Holy Spirit is making clean what was unclean. Peter, like Jesus before him, has no hesitation about touching the corpse of a stranger. Afterwards, he stays for ‘many days’ with Simon, a tanner, whose dirty and smelly trade working with the bodies of dead animals was unlikely to have been located in the ‘nicer’ parts of town. After he heals Aeneas, ‘all the residents of Lydda and Sharon saw him, and they turned to the Lord’ (v. 35, emphasis added), suggesting that both Jews and Gentiles were hearers of the good news.

The powerful message that Peter brings in the name of Christ is for everyone: those who are far off, and those who are near (Ephesians 2:17). It’s given to the ‘person’ Aeneas, the ‘disciple’ Tabitha, and the mighty centurion Cornelius. The message speaks to Roger II, Norman warrior-king of multicultural Sicily, to the wily merchants and traders of Medici Florence, and to the suave and refined connoisseurs of Casanova’s Venice. It brings down the mighty from their seats (Saul and Cornelius) and exalts those of low degree (Aeneas and Tabitha). As the central narrative arc of the book of Acts proclaims, it goes throughout the whole world, as a testimony to all the nations.

Commentaries by Ben Lima