Acts of the Apostles 10:1–48; 11:1–18

Peter in the House of Cornelius

Sonya Clark

Many, 2019, Woven cloth, 9.14 x 4.57 m; ©️ Sonya Clark; Photo: Carlos Avendaño

Weaving a Larger World

Commentary by Michael Wright

Flags are symbols that gather various associations into shared values and histories. But what happens when what a flag represents isn’t shared at all? When a flag perpetuates a story that needs to change?

These were the kind of questions on Sonya Clark’s mind when she discovered the original Confederate truce flag in the National Museum of American History. She asked:

Why do we know the Confederate Battle Flag instead of the Confederate Truce Flag that marked surrender, brokered peace, and was a promise of reconciliation? What would it mean to the psychology of this nation if the Truce Flag replaced the flag associated with hate and white supremacy? (Fabric Workshop 2019: 1)

Clark realized that many of today’s racial problems in the US come from a distorted story about the American past, and that perhaps by addressing the symbol of the flag, she might provoke others to imagine a different social fabric.

In Many, the artist invited museum staff to weave one hundred Confederate truce flags. It’s not enough for one person to learn a new story; Clark translated this history into an interactive project on a large scale in which people were invited to re-narrate this history for themselves. The change she sought pushed this act of weaving into the register of ritual—shared, embodied experiences to provoke transformation of the mind and heart.

At the beginning of Acts 11, the Apostle Peter is in a similar situation as the artist. When he returned to the church at Jerusalem, he returned to a community in conflict. Could uncircumcised people be part of the Way or not?

It wasn’t just arguing about a social symbol—their opinions on the symbol represented social commitments about who was in the community and who was out.

Peter, aware of these dynamics, translates what happened in the house of Cornelius into the ongoing history of his community. He interprets his journey to Caesarea in theological terms—‘the Spirit told me to go with them, making no distinction’ (11:12)—and helps his community interpret the conversion of outsiders through their shared memories of Pentecost: ‘Holy Spirit fell on them just as on us at the beginning’ (11:15).

Both artist and apostle are not only telling new stories about the past; they’re giving their listeners opportunities to interact with it, to tell the story of a more expansive community, and be changed in the process.

References

Fabric Workshop. 2020. Sonya Clark: Monumental Cloth, The Flag We Should Know (Philadelphia: Fabric Workshop and Museum)

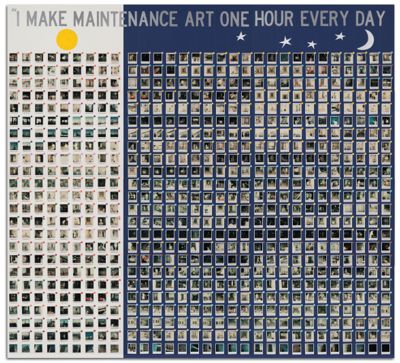

Mierle Laderman Ukeles

I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day, 1976, 720 collaged dye diffusion transfer prints with self-adhesive labels, graphite pencil, collaged acrylic on board, and self-adhesive vinyl on paper, Variable, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchase, with funds from the Photography Committee and The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, 2017.164a-b, ©️ Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

Listening to the Hum of Living

Commentary by Michael Wright

Inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s readymades—and the way Duchamp and the artists he inspired named art for themselves—Mierle Laderman Ukeles nevertheless uncovered a problem. By elevating ordinary things to the status of art objects, such artists often obscured the social structures that make museums and galleries possible in the first place.

So Ukeles reconceptualized her approach to art-making, and developed Maintenance Art. Maintenance Art unearths the systems that sustain the art world, and provokes consideration of the invisible labour that makes it possible.

In I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day (1976), Ukeles collaborated with over 300 maintenance workers at the original Whitney Museum. For more than five weeks, she asked custodians, plumbers, and other labourers to name an hour out of their work shift as a time when they were undertaking ‘maintenance art’, and to document these moments with a camera.

Ukeles was transferring her ‘naming authority’ as an artist to those without a voice, and by the end of the project, she covered a museum wall with documentation of these new artists. The resulting collage of images both uncovered and dignified an invisible working class that maintained the life of the museum as viewers walked through its halls.

Peter’s vision of a sheet unfurling above Joppa functions in a way that is comparable to Ukeles’s grid of images. Heaven opened to reveal a bounty of ‘unclean’ animals and, three times, a voice said ‘Rise, Peter; kill and eat … What God has cleansed, you must not call common’ (10:13, 15). If Jewish food codes can be interpreted as shaping who eats together as much as what is eaten, then Peter’s vision likewise presented him with more than just food. Like I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day, it revealed a community of outsiders (those who eat unclean food) as those he must now accept. It provoked him to reorient his social values.

Ukeles wrote in her manifesto that she was ‘trying to listen to the hum of living’ (Ryan 2009). Maintenance Art, then, is the practice of a certain kind of vision—to see all people, especially those obscured by hierarchies and the built environment, as part of a shared life. Whether pondering Maintenance Art or receiving a mystical vision, we too are invited to change the way we see others. To join in a ‘hum of living’ that’s much larger than the social boundaries that can limit our worlds.

References

Ryan, Bartholomew. 2009. ‘Manifesto for Maintenance: A Conversation with Mierle Laderman Ukeles, 18 March 2009’, Art in America, available at https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/interviews/draft-mierle-interview-56056/ [accessed 14 October 2022]

Ukeles, Mierle Laderman. 2014. ‘Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969: Proposal for an Exhibition CARE’, in Feminist Art Manifestos: An Anthology, ed. by Katy Deepwell (London: KT Press)

Sarah M. Rodriguez

Travertine Aggregate, 2019, Resin, dirt, clay, snakeskin, 142.2 x 76.2 cm; ©️ Sarah M Rodriguez, photo by Martin Elder

Unexpected Landings

Commentary by Michael Wright

The works in Sarah M. Rodriguez's Aggregate series are less depictions of landscapes and more the result of intimate collaboration with them. The artist hiked throughout Los Angeles, collecting dirt and clay and making plaster casts of animal prints she discovered. After months, she pressed them into a mixture of soil and resin.

Where landscape painting traditions represent idyllic scenes and ignore the various biological sources of canvases, brushes, and pigments, these sculptures present the environment. Rodriguez’s Travertine Aggregate questions the assumption that artists stand outside the world to depict it and suggests that art emerges when artists open themselves to the agencies of others (Wright 2020). The deep-ecology philosopher Arne Naess would call this searching for the ‘ecological self’ (Naess 1995: 226), an identity based not apart from nature but entangled within it.

The trajectory of Peter’s changing sense of his leadership in Acts develops toward a similar insight. In the early chapters, Peter leads a fledging church; he helps them search for a new apostle (1:15) and defines their values as he confronts Ananias and Sapphira (5:1–11). He preaches with confidence at Pentecost (2:14) and on Solomon’s Portico (3:11–26), and he’s so ‘filled with the Holy Spirit’ (4:8) that some Jewish leaders recoil from his ‘boldness’ (4:13). His reputation as a healer spreads so wide that the lame begin to lay in his path so that ‘at least his shadow might fall on some of them’ (5:15).

But Acts 10 doesn’t begin with Peter’s leadership; instead, the centurion Cornelius, prompted by an angel, sends for him. Meanwhile, a vision leaves Peter ‘perplexed’ (10:17) and ‘pondering’ (10:19). And when Peter visits Cornelius’s house, he begins not with preaching but with questions: ‘what is the reason for your coming? … Why have you sent for me?’ (10:21, 29). Peter doesn’t lead, preach, or heal. Instead: he listens. God, through Cornelius and his household, invites Peter to journey past the threshold of his own agency.

Peter’s experience and the Travertine Aggregate have this risk in common: both artist and apostle begin their work not from their own designs but from attending to forces beyond their control. Rodriguez’s vision didn’t start with the self but instead emerged out of a dialogue with the land. Likewise, Peter didn’t bring good news to outsiders but rather discovered that it was already afoot, entangling communities together across their social boundaries.

References

Naess, Arne. 1995. ‘Self-realization: An Ecological Approach to Being in the World’, in Deep Ecology for the Twenty-First Century, ed. by G. Sessions (Boston: Shambhala)

Wright, Michael. 2020. ‘Personal interview with the artist, Los Angeles, January 2020’

Sonya Clark :

Many, 2019 , Woven cloth

Mierle Laderman Ukeles :

I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day, 1976 , 720 collaged dye diffusion transfer prints with self-adhesive labels, graphite pencil, collaged acrylic on board, and self-adhesive vinyl on paper

Sarah M. Rodriguez :

Travertine Aggregate, 2019 , Resin, dirt, clay, snakeskin

The Conversion of the Imagination

Comparative commentary by Michael Wright

Acts 10 begins not with the acts of apostles but with the acts of outsiders in Caesarea.

The centurion Cornelius, known in the Roman naval town as a devout man, encountered an angel of God who directed him to reach out to Peter who was staying nearby in Joppa. That following day, Peter’s own vision left him both ‘inwardly perplexed’ (10:17) but also ready when he was asked to journey back to Cornelius’s household.

Acts 10, then, is not the story of one conversion but two: Cornelius’s conversion to Christian faith and a conversion of Peter’s imagination as the church expanded beyond his expectations. Both men were asked to go to the edges of their understanding and risk something unknown.

This sense of attentiveness beyond ego and intent is central to Sarah Rodriguez’s Aggregate sculptures. Instead of asserting authority over the land and its inhabitants, the artist strains to attend; to let something emerge beyond her own plans. This is the inciting force of Acts 10: not active decisions to expand the Church, but God enticing two men to encounter communities beyond what they imagine their social arrangements to enjoin. Terrified and perplexed, they’re jostled into a readiness to risk beyond their own plans and assumptions.

For Peter, this sense of risk comes from who it is that he’s being asked to meet—an outsider to the young Jewish sect of Christ. So, where the vision to Cornelius is more direct (‘send men to Joppa, and bring one Simon who is called Peter; 10:5), the vision to Peter comes through aesthetic means. Three times, a sheet of unclean animals spills out onto the roof in Joppa; three times, Peter wrestles with the image and its social implications. The vision is not only a display of Jewish dietary codes; it slowly converts Peter’s imagination and his values. Like the bitter lesson of his threefold denial of Jesus (Luke 22:54–62), this vision is meant to educate the apostle—to help him grow beyond his own social limits where the Spirit is at work.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day echoes this vision. Like the sheet falling from the heavens, the grid of Polaroids makes outsiders legible. But the vision and artwork echo one another at a deeper level. Both unearth an unquestioned social boundary and dignify the community of people made invisible by it. The vision of the sheet questions the Jewish boundaries of clean and unclean, and demands that Peter see the dignity of people on the other side of these food laws. Ukeles questions the unacknowledged pressures of class and demands that viewers see the dignity of people who maintain it. Both educate the eye, the imagination, and, finally, the heart.

Shocked into readiness, Peter travels up the coast to meet with Cornelius and finds that the Spirit of God is already moving under the roof of his home, and after preaching, he witnesses Cornelius and his household speaking in tongues and invites the first Gentile converts into the young Church. He asks, ‘Can any one forbid water for baptizing these people who have received the Holy Spirit just as we have?’ (10:46)—a question signalling his own ongoing conversion as the boundaries of the young church expand.

But Peter is far away from his Christian friends. How do you tell this story back in the church in Jerusalem, especially as they fight over circumcision (another social marker of who’s in and who’s out)? You weave the new story into the shared memories of the community. When Sonya Clark discovered the Confederate truce flag, her personal sense of history shifted on its axis. But that was not enough—she needed to invite others to experience that same shift; to re-narrate this story into their own lives. This is why, after Peter retells the story of meeting Cornelius to the Church, he adds:

As I began to speak, the Holy Spirit fell on them just as on us at the beginning. And I remembered the word of the Lord, how he said, ‘John baptized with water, but you shall be baptized with the Holy Spirit’. If then God gave the same gift to them as he gave to us when we believed in the Lord Jesus Christ, who was I that I could withstand God? (11:15–17)

He reminds the young Church of their own experience of speaking in tongues (Acts 2) and of the very words of their Teacher (Acts 1:5). Peter helps them re-weave their shared memories into an enlarged sense of their living community.

This story, like these artworks, make social boundaries legible and help us approach them through humility and risk. And as we do so, we may discover beyond our assumptions the same Spirit waiting for us in a larger world.

Commentaries by Michael Wright