Revelation 10

The Angel and the Book

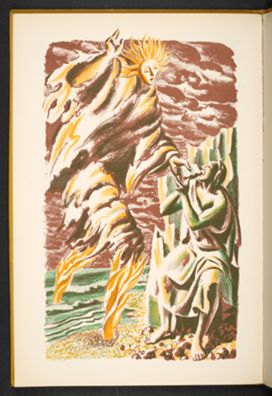

Hans Feibusch

An Angel Appeareth with a Book, from The Revelation of Saint John the Divine with Lithographs, 1946, Lithograph, 304.8 x 381 mm, The British Library, London; p.26, © The British Library Board L.R.298.dd.2

The Prophetic Artist

Commentary by Ian Boxall

In this dynamic image, one of a series of lithographs published in book-form in 1946, Hans Feibusch (1898–1998) presents the moment of John’s prophetic inspiration. John devours the ‘little book’ of God’s word in the angel’s left hand. The energy in the angel’s posture evokes the Spirit-breathed inspiration John now receives. Having consumed this book, he will ‘again prophesy about many peoples and nations and tongues and kings’ (Revelation 10:11). He is seated on a rock, resembling a chair or throne, symbol of the teaching authority he now possesses.

Many will know Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut of this scene in his 1498 Apocalypsis cum figuris, on which Feibusch draws. Yet Feibusch has made the subject his own, in light of his experience. A German Jewish artist who fled to England in May 1933 following Nazi denunciation of his work, his story mirrors that of his subject. Like John of Patmos, this John (Hans=Johannes) too has crossed a sea to his place of exile and inspiration. This New Testament image, produced in the aftermath of the Second World War, hints at that spiritual journey which would eventually lead Feibusch into the Church of England.

Does Feibusch regard the prophet John as a type of the inspired artist, as did so many of his artistic forebears (e.g. Botticelli, Duvet, Velázquez, even Dürer)? He suggests as much in words published in the same year as his Revelation lithographs, calling for a renewal of religious art to speak to those haunted by the horrors of war. Though his main subject is mural-painting, his words are equally apt for John’s Apocalypse:

Only the most profound, tragic, moving, sublime vision can redeem us. The voice of the Church should be heard loud over the thunderstorm; and the artist should be her mouthpiece, as of old. (Feibusch 1946: 92)

References

Coke, David (ed.). 1995. Hans Feibusch: The Heat of Vision (London: Lund Humphries)

Feibusch, Hans. 1946. Mural Painting (London: Adam and Charles Black)

Eucharist on Patmos

Commentary by Ian Boxall

John tells us that he received his vision on the remote island of Patmos ‘on the Lord’s Day’ (Revelation 1:10). Sunday, the day of the resurrection, was the day on which early Christians gathered to celebrate the Eucharist. John says nothing more about this context. Did he experience his vision while worshipping with fellow Christians? Or was this a solitary experience? Western art has tended to imagine John alone, apart from the presence of an eagle, his traditional symbol in Christian iconography. Eastern tradition, by contrast, has John accompanied by his disciple and scribe Prochorus (see Acts 6:5), and engaged in intense prayer and fasting.

Debates about John’s setting notwithstanding, this particular passage has eucharistic undertones which are frequently overlooked. John receives his revelation not primarily by hearing or even reading, but by ingesting. Readers of the Gospels will hear in the heavenly command to ‘Take it and eat’ (labe kai kataphage auto, literally ‘Take and devour it’) an echo of Christ’s command to his disciples at the last supper (labete phagete, ‘Take and eat’, Matthew 26:26). The connection is not lost on Hans Feibusch. His angel gently places the book in John’s open mouth, as if administering the host, while extending his right hand in the pose of priestly blessing. In response, John raises his hand to receive the heavenly gift. Like the faithful communicant, he is to embody what he now ingests.

This echo of Christ’s words of institution takes on added significance if, as many scholars believe, John’s Apocalypse was intended to be read aloud to Christians in the seven churches of Asia when they gathered for their own eucharistic celebrations. The ‘words of prophecy’ (1:2) they heard are as transformative and life-giving as the bread and cup they received. Word and sacrament: both are potent expressions of Christ’s living presence.

References

Coke, David (ed.). 1995. Hans Feibusch: The Heat of Vision (London: Lund Humphries)

Unknown artist

The Angel with the Book, c.1860, Wood engraving, 31.2 x 38.1 cm; World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

A Sea-Calming Colossus

Commentary by Ian Boxall

Revelation 10’s mighty angel impresses by his acrobatic skills. He is able to straddle both land and sea, like Christ himself, who walks on the Sea of Galilee without sinking (Matthew 14:22–33; Mark 6:45–52; John 6:16–21). In this dramatic wood engraving of the scene, from a nineteenth-century illustrated Bible, the delicate poise of the angel’s feet contrasts with his muscular, colossal upper body. ‘Colossal’ is an appropriate adjective, for this engraving, in common with several nineteenth-century depictions of this angel, consciously mirrors the Colossus of Rhodes. The rays emanating from his head recall the sun-god Helios, whose statue straddled the entrance to Rhodes harbour. That wonder of the ancient world, re-imagined by Martin Heemskerk in his widely known engraving of 1570, serves as an appropriate model for John’s solar-faced angel.

This engraving also shows the influence of Benjamin West’s A Mighty Angel Standeth upon the Land and upon the Sea (c.1797). Yet, in contrast to West’s painting, where the angel treads turbulent waters, the sea in this engraving is as calm as a millpond. The book of Revelation, like the Bible as a whole, views the sea as a place of danger, evil, and chaos, from which the beast emerges (Revelation 13:1–8). John’s location on the island of Patmos added a further dimension, since the surrounding waters of the Aegean were dominated by Rome, the beast’s current incarnation. The engraver visualizes the effects of the angel’s descent. Like the ‘sea of glass, like crystal’ that John previously saw in heaven (4:6), this sea has now been subdued. It has lost its ability to threaten, as heaven’s herald announces to the earth that ‘there should be no more delay’ (10:6). The roaring of the lion (10:3) has tamed the turbulent waters. The scene is set for Revelation’s climax, when the sea will be no more (21:1).

References

Boxall, Ian. 2015. ‘The Mighty Angel with the Little Scroll: British Perspectives on the Reception History of Revelation 10’, in The Book of Revelation: Currents in British Research on the Apocalypse, ed. by Garrick V. Allen et al (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck), pp. 245–63

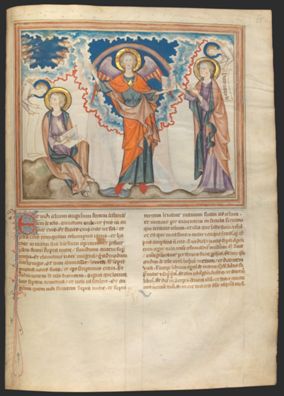

Unknown artist

The Angel with the Book, from the Cloisters Apocalypse, c.1330, Tempera, gold, silver, and ink on parchment, 308 x 230 mm, The Cloisters, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Cloisters Collection, 1968, 68.174, fol. 16r, www.metmuseum.org

A Christ-like Angel

Commentary by Ian Boxall

The angel John sees descending from heaven in Revelation 10 is a new character in the story (‘another mighty angel’). Yet he is also surprisingly familiar. His sun-like face and legs like pillars of fire recall the Son of Man in Revelation’s opening vision (feet ‘like burnished bronze’, face ‘like the sun shining at full strength’; 1:15–16). His lion-like voice evokes Christ the slaughtered Lamb, who is also ‘the Lion of the tribe of Judah’ (5:5). For this reason, many patristic and medieval commentators interpreted this passage as of Jesus. An alternative possibility is this mighty angel is not Christ himself, but Christ’s own angel, acting as his messenger and mediator.

This image from the fourteenth-century Cloisters Apocalypse, one of many Anglo-Norman illuminated Apocalypse manuscripts produced in England and France from the mid-thirteenth century onwards, explores the ambiguity. The angel, standing at centre, dominates the page. A red cross is visible in his halo, a clear symbol of Christ. Yet, unlike images of Jesus elsewhere in Cloisters (e.g. fol. 6r, depicting Revelation 5:7–14, or fol. 38r, illustrating Revelation 22:10–21), or the bearded angel of Revelation 10 in the earlier Abingdon Apocalypse (c.1270–75; British Library Add. MS 42555, fol. 27v), he is unshaven. He is both like Christ, and unlike Christ.

The angel’s role as mediator between heaven and earth, between Christ and John, is also effectively conveyed by his posture. His raised right hand, by which he swears ‘by him who lives for ever and ever’ (10:6), is positioned in parallel to the cloud extending heavenwards. With his left hand, he offers the little book or ‘little scroll’ to the human John. Thus all three stages in the chain of revelation—God/Christ, his angel, his servant John (1:1)—are presented visually. Christ has delivered his revelation through his angelic mediator. His earthly prophet can now proclaim its bitter-sweet message.

Thunder Silenced

Commentary by Ian Boxall

The illuminator of the Cloisters Apocalypse exploits the capacity of visual art to present several scenes from a narrative synchronically. This image visualizes almost the whole of Revelation 10 (vv.1–9), the Vulgate text of which has been transcribed underneath. The mighty angel, adorned with cloud and rainbow (v.1), simultaneously raises his right hand to swear an oath (vv.5–6), and hands over the book so that John, standing on the far right, can consume it (vv.8–11).

Yet the dominance of the angel should not obscure the scene on the left. Above in the heavenly realm are seven dogs’ heads, framed by a cloud, symbolizing the seven thunders (v.3). Below, John sits on a rock on Patmos. He is interrupted by another angel, frustrating his attempt to write down the content of the thunders (evidently heard as intelligible sounds).

The command from heaven—‘Seal up what the seven thunders have said, and do not write it down’ (v.4)—is surprising in an apocalypse. Normally, the act of sealing follows writing, to preserve a revelation until it can be made known (e.g. Daniel 12:4; 4 Ezra 14:26, 45–46). Here, by contrast, sealing up prevents the thunders’ message from being recorded. John is not told why, and it is left to the artist to hint at possibilities. Are the thunders (seven, a perfect number) symbols of God’s thundering presence (e.g. Job 37:4–5; Psalm 29:3)? Or do they represent divine judgments, like the trumpet plagues visualized on the preceding pages in Cloisters, now silenced as the mighty angel conveys a new prophecy? If the latter, then their silencing may denote a new divine strategy, revealed in the ensuing chapters. John will describe a story of a male child, born of a heavenly woman, who wins the victory, not by divine violence but by the shedding of his blood (Revelation 12).

References

Deuchler, Florens et al. 1971. The Cloisters Apocalypse: An Early Fourteenth-Century Manuscript in Facsimile, 2 vols (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

O’Hear, Natasha. 2001. Contrasting Images of the Book of Revelation in Late Medieval and Early Modern Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Hans Feibusch :

An Angel Appeareth with a Book, from The Revelation of Saint John the Divine with Lithographs, 1946 , Lithograph

Unknown artist :

The Angel with the Book, c.1860 , Wood engraving

Unknown artist :

The Angel with the Book, from the Cloisters Apocalypse, c.1330 , Tempera, gold, silver, and ink on parchment

Visualizing Angels

Comparative commentary by Ian Boxall

The Epistle to the Hebrews famously reminds its readers that some have entertained angels unawares (Hebrews 13:2; see also, Genesis 18:1–8). Angels in the biblical tradition, like the gods of Greece and Rome, frequently appear on earth in human form. Yet not all angels assume such a disguise. The rich panoply of angels in John’s apocalyptic vision makes no attempt to hide their heavenly origin. They fly (e.g. Revelation 14:6); they minister in the heavenly sanctuary (e.g. 8:3–5); they descend, like the mighty angel John describes in this passage (10:1). Nonetheless, the artist still faces a challenge when depicting them visually. What do angels look like? How does the heavenly realm manifest itself to the terrestrial, in the chaotic, topsy-turvy, apocalyptic world unveiled in Revelation? In particular, how can the kaleidoscope of details attributed to this particular angel be effectively portrayed?

In the tradition of Anglo-Norman illuminated apocalypses, the Cloisters Apocalypse chooses artistic convention over slavishly-literal depiction of the biblical text. His Christ-like features notwithstanding, this angel is typically Gothic. He is youthful, a nod in the direction of angelic immortality, and has androgynous features. He has prominent, colourful wings, their size not only proportionate to his body, but hinting at the speed of his flight from heaven. Rather than him being ‘wrapped in a cloud’, the latter functions as a backdrop, marking the boundary between earth and heaven. There is just a mere hint of the ‘legs like pillars of fire’ in the fiery-red feet visible below the angel’s tunic.

But perhaps most striking is the direction of the angel’s gaze. He looks, not at John, but out from the page at the viewer. His divine message—that there should be ‘no more delay’, that the end is already breaking into the present—is addressed to the wealthy, probably aristocratic owner of the manuscript. With John as surrogate, the viewer is to enter, page-by-page, into this visual world where humans and angels interact, and be transformed as a consequence.

The angel of the wood engraving also gazes out at the viewer, but with an expression which is more terrifying than serene. Angels are not to be trifled with. His raised right hand, fingers apart, suggests less oath-taking than a posture of warning. Moreover, his superiority over humans is evident in his immense height, dwarfing even the rocky outcrop on Patmos in the foreground. This mighty angel, like the Christ he represents, is truly awesome. Yet he is also less substantial than the robust, colourful angel of Cloisters. He emerges out of the clouds, the light emanating from his head indistinguishable from the sun’s rays bursting through rain clouds, promising the appearance of a rainbow. This engraving presents a much more modern take on the problem of divine communication: what does one really see? An angel, or a rather dramatic cloud formation?

Hans Feibusch, standing in the tradition of Albrecht Dürer (1498) and Jean Duvet (1555), treats this character differently from his other heavenly beings, whom he portrays as more conventionally angelic, albeit wingless. For Feibusch, the composite character of this figure dominates. Yet his is much more successful than the stilted, overly-literal image produced by Dürer. The angel is on the move, as energetic as the flames of fire which form his legs, or the billowing clouds covering his torso. The whole image is suffused with the light emanating from his sun-like face. Moreover, in sharp contrast to the stern angel in the Victorian engraving, the face of Feibusch’s angel exudes an almost maternal tenderness. The youthful John is a child who needs to be nurtured as he prepares for his prophetic future.

Inviting in Cloisters; terrifying in the nineteenth-century engraving; maternal in Feibusch: this mighty angel has many faces. But, alone of the three, the Cloisters Apocalypse makes a further point about angelic communication. The mighty angel is not the only heavenly messenger visible in the image. To the left, an angel interrupts John’s writing down the message of the seven thunders. In the top right-hand corner, another angel appears, holding a scroll containing the Latin words Vade accipe li[brum] (‘Go, take the book’). Yet in both cases in the biblical text, John sees nothing (10:4, 8). He merely hears a voice from heaven, conveying the divine message. These two lesser angels in Cloisters remind us that heaven often communicates in less overt and dramatic ways. Hearing as well as seeing. Listening to that still, small voice. And, in listening, perhaps entertaining angels unawares.

References

Boxall, Ian. 2015. ‘The Mighty Angel with the Little Scroll: British Perspectives on the Reception History of Revelation 10’, in The Book of Revelation: Currents in British Research on the Apocalypse, ed. by Garrick V. Allen et al (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck), pp. 245–63

Coke, David (ed.). 1995. Hans Feibusch: The Heat of Vision (London: Lund Humphries)

Deuchler, Florens et al. 1971. The Cloisters Apocalypse: An Early Fourteenth-Century Manuscript in Facsimile, 2 vols (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Feibusch, Hans. 1946. Mural Painting (London: Adam and Charles Black)

O’Hear, Natasha F.H. 2001. Contrasting Images of the Book of Revelation in Late Medieval and Early Modern Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Commentaries by Ian Boxall