Revelation 12:1–6, 13–17

The Woman and the Dragon

Sandro Botticelli

'Mystic Nativity', 1500, Oil on canvas, 108.6 x 74.9 cm, The National Gallery, London; Bought 1878, NG1034, © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

Mercy and Truth are Met Together

Commentary by Robin Griffith-Jones

She brought forth a male child, one who is to rule all the nations with a rod of iron (Revelation 12:5)

Sandro Botticelli’s The Mystic Nativity is a patently joyous painting. From an opening in heaven, golden as the sun, a circle of twelve dancing angels links heaven and earth. These—and all the painting’s angels—wear white, green, or red, for the cardinal virtues faith, hope, and love. Between them they hold olive branches, symbols of mercy and of peace. On each branch flutters a ribbon with a Latin or Italian inscription in praise of the Virgin Mary: ‘Sanctuary beyond words’, ‘Mother of God’, ‘Virgin of Virgins’, ‘Wondrous Bride of God the Father’, ‘Virgin Mother’, ‘Hope of Sinners’, ‘Queen over All’, ‘Only Queen of the World’. From the branches hang small crowns.

In the central register, an enormous Mary kneels before the infant Jesus. Beside them sits Joseph, elderly and balding. He might almost be asleep, for he was a man, like his namesake in the Old Testament, who dreamed dreams (Matthew 1:20; 2:13). Behind the stable and a darkly mysterious wood, the Sun of Righteousness is about to rise. On each side of the Holy Family, more olive-bearing angels present visitors: the shepherds certainly, and perhaps the Magi. The olive on the left bears another banderole, ‘Behold the lamb of God’.

In the foreground register three angels and three humans embrace. Once more the angels’ ribbons speak for them: ‘Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to everyone of good will’ (Luke 2:14). Scurrying away into crevices from this wonderful scene is an assortment of tiny devils, their evil aims defeated.

‘Mercy and truth are met together’, says the psalmist; ‘righteousness and peace have kissed each other’ (Psalm 85:10). It would be hard to envision a lovelier depiction of the joy of heaven to earth come down.

So far, so good. But the scene is the Nativity. Why is this picture not nestling among the Christmas commentaries?

Well, it would be, if Botticelli himself had not written a cryptic inscription along the painting’s top. We come back to his inscription in the next commentary. For the moment we can simply relish his disclosure of joy in heaven and on earth.

Apocalypse Now

Commentary by Robin Griffith-Jones

And the great dragon was thrown down, that ancient serpent, who is called the Devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world—he was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him. (Revelation 12:9)

We ended the previous commentary with reference to Sandro Botticelli’s cryptic inscription along the painting’s top. It is in Greek, incomprehensible to most of Botticelli’s contemporaries. Botticelli wanted—needed?—to be mysterious. Here it is:

THIS PAINTING AT THE END OF THE YEAR 1500 IN THE TROUBLES OF ITALY I ALEXANDER, IN THE HALF-TIME AFTER A TIME, WAS PAINTING IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE ELEVENTH [CHAPTER] OF SAINT JOHN IN THE 2ND WOE OF THE APOCALYPSE IN THE LOOSING, FOR THREE-AND-A-HALF YEARS, OF THE DEVIL. THEN HE WILL BE BOUND IN THE 12TH AND WE WILL SEE HIM ABOUT TO BE BURIED SIMILAR TO THIS PAINTING.

Revelation 11 tells of two witnesses who testify for three-and-a-half years and are then killed by the beast coming up from the abyss (v.7). ‘The Second Woe has been and gone. Look, the Third Woe is coming soon’ (v.14, own translation).

Botticelli was painting in Florence, at the beginning (in our modern calendar) of 1501. The French had invaded in 1494 and again in 1499. From September 1494, the Dominican mystic and preacher Fra Girolamo Savonarola had relentlessly threatened God’s punishment of the city. Savonarola and his follower Fra Domenico da Pescia preached for almost exactly three-and-a-half years until they were burnt at the stake in May 1498. Here, perhaps, had been the two prophets foreseen in Revelation 11. The banderoles of Botticelli’s heavenly angels bear the words of Savonarola’s own hymns to the Virgin.

The Mystic Nativity certainly recalls Revelation: in the open heaven (4:1), the twelve angels for stars above the Virgin (12:1), and those defeated devils (12:8). But the tone is so different: Botticelli’s angels have a playful grace, his devils are almost risible. There are hints of ‘Woe’ to come: the donkey bears on the neck the mark of a cross; the cave and swaddling-clothes portend burial. Yet the painting as a whole radiates joy.

Here was an artist, working in personal and civic turmoil, who could look through and beyond it to a depiction—so uplifting—of its resolution. It is as if he could see dreams as strange and as wise as the dreams of Joseph.

Diego Velázquez

The Immaculate Conception, 1618–19, Oil on canvas, 135 x 101.6 cm, The National Gallery, London; Bought with the aid of The Art Fund, 1974, NG6424, © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

Celestial Signs

Commentary by Robin Griffith-Jones

And a great portent appeared in heaven, a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars; [and] she was with child. (Revelation 12:1)

For a moment we must look away from the art around us to gaze at the splendour of the skies above us. Diego Velázquez painted The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, c.1618, early in his career, probably for the Carmelite Convent of Our Lady in Seville. It is a study of Revelation 12; and of the night sky itself. To see what is to be seen in the passage and the painting, set aside your computer one night when you are away from any urban glare, go outside, and look up at the vast order of the heavens. What do you see there? Our forebears saw of course the majestic movements of the sun, moon, and planets against the background of the stars. And more than that: they (literally) joined the dots, to see figures of destiny inscribed, on a huge scale, in the patterns of the stars.

The Greek sēmeion means a ‘sign’, sometimes a (portentous) ‘constellation’. The woman in Revelation 12 is almost certainly the constellation of the winged Pregnant Woman (in Greek, Parthenos or Virgin, our Virgo). She is ‘clothed with the sun’ in September; and each month the moon passes her feet. The twelve stars around her head may be Leo, but more probably represent the zodiac as a whole. Jupiter, king of the planets, is in Virgo once every 11–12 years; he may here be the imperial son ‘who will shepherd the nations with an iron rod’ (Revelation 12:5). The red dragon is probably the southern constellation Scorpio. The serpent of Eden (Genesis 3) is now revealed as a cosmic dragon, heir to the Greeks’ Python and Egypt’s Typhon.

The seer was ordered at Revelation 11:1 to measure the Temple on earth; at Revelation 11:19 the heavenly prototype of its innermost sanctuary is opened and the Ark of the Covenant seen. God’s home and plans are laid open to view, and are fittingly inscribed on the heavens in the great Parthenos herself, the Ark who for nine months bore God’s new Covenant in her womb.

Queen of Heaven and Earth

Commentary by Robin Griffith-Jones

And she cried out in her pangs of birth, in anguish for delivery. (Revelation 12:2)

The Carmelites, for whom Diego Velázquez probably made this painting, traced their origins to the Old Testament prophet Elijah, who saw on Mount Carmel ‘a little cloud rising from the sea’ (1 Kings 18:44). For the Carmelites, this cloud prefigured the Virgin Mary and her conception free from any stain (macula) of original sin.

Velázquez has surrounded the Virgin with clouds, trees, and sea, the attributes of God’s own Wisdom as Wisdom herself describes them in Ecclesiasticus 24:

I covered the earth like mist, my throne was a pillar of cloud. I alone have made a circuit of the heavens. I have grown tall as a cedar on Lebanon, as a cypress on Mount Hermon, as a palm in En-Gedi. I am like a conduit from a river, and my river has grown into a sea. (vv.3–5, 13–14, 31, own translation)

Meanwhile, the bridegroom speaks of his bride in the Song of Solomon: ‘She is a garden enclosed, a sealed fountain. Who is this rising like the dawn, fair as the moon, resplendent as the sun?’ (4:15; 6:10, own translation) So the Church speaks of Mary, virgin-mother; the painting’s circular temple is based on Rome’s temple to the virginal Vesta.

The woman in this vision is there for all to see. The sign simply ‘was seen’ (v.1); the seer does not say that as a privileged mystic ‘I saw’. We become the visionaries. The constellations take body and life. A young woman, far larger than the moon, emerges from the sun to fill the heavens. She is modest and demure; she is perhaps modelled on Velázquez’s own sister Juana (b.1609). This is a Queen of Heaven and earth alike with no crown or clutter, of an age to become the virginal mother of Jesus and so of all his beloved disciples (John 19:26–27).

We nowadays revere astronomy; astrology, we disregard. To read Revelation we need to re-learn something of astrology’s language. Not in order to credit its claims; but to sense the disclosure of God’s purposes in the vast complexity of the heavens, here come down, on a beautifully translucent moon, to be within reach of us and of our hearts on earth.

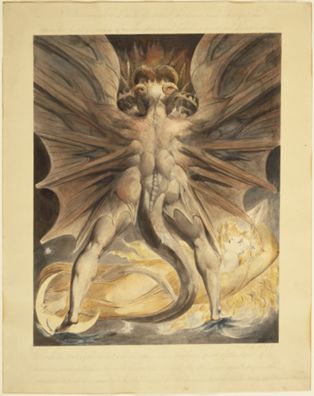

William Blake

The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun (Rev 12:1–4), c.1803–05, Black ink and watercolour over traces of graphite and incised lines, 437 x 348 mm, Brooklyn Museum; 15.368, Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York, USA / Gift of William Augustus White / Bridgeman Images

The Study of Archangels

Commentary by Robin Griffith-Jones

And another portent appeared in heaven; behold, a great red dragon, with seven heads and ten horns, and seven diadems upon his heads. His tail swept down a third of the stars of heaven, and cast them to the earth. (Revelation 12:3–4)

What an extraordinary image. In a large watercolour (437 x 348 mm), William Blake has evoked a vast and terrifying monster, threatening the radiant Woman with dire physical—and sexual—violence. There is no sign of her escape, promised in Revelation 12:6. She lies supine, utterly vulnerable, stars scattered around her.

Blake created an elaborate mythology of his own. In conventional religion of ‘the primeval priest’s assum’d power’ (Blake 2008: 70), in a dominant rationalism, in the political and economic structures in England, he saw a systemic oppression of soul and body together. His demiurge Urizen—a play on ‘Your Reason’—reduced the world both to measured definition and to chains.

Blake welcomed the American and French revolutions and the energy which they represented and released. He famously wrote of Milton in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell:

The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devils party without knowing it. (Blake 2008: 35)

Even in our watercolour the towering dragon—figure of the world’s most ruthless oppressors—has a majestic power that fascinates as much as it repels.

Blake was a visionary, for whom soul and body cohered; but for him there was still an Eternity beyond normal sight, to which ‘in the regions of my Imagination’ both Blake and all those who took his lead had access (Blake 1956: 43). He wrote to John Flaxman in 1800:

In my brain are studies & Chambers fill’d with books and pictures of old, which I wrote & painted in ages of Eternity before my mortal life; & those works are the delight & Study of Archangels. (Blake 1956: 51)

Blake did not set out just to illustrate Revelation, but to reveal its angelic mysteries. He demands a visceral response to this terrible scene. The cool analysis of ancient and discarded myths, indispensable to modern scholarship, would be for Blake the work of Urizen. Revelation mattered to Blake because it revealed the power structures of the present world.

References

Blake, William. 1956. The Letters of William Blake, ed. by Geoffrey Keynes (New York: Macmillan)

———. 2008. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. by David V. Erdman and Harold Bloom (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press)

Seeing Everything Infinite

Commentary by Robin Griffith-Jones

And the dragon stood before the woman who was about to bear a child, that he might devour her child when she brought it forth. (Revelation 12:4)

We might find The Great Red Dragon spell-binding but creepy. The scene is crudely gendered. The fault here, if there is one, is the Bible’s rather than William Blake’s. Revelation sets up programmatic contrasts: between the Woman attacked by the Dragon and the Whore of Babylon who rides a scarlet beast (17:3); and then between the Whore and the New Jerusalem ‘prepared as a bride for her husband’ (21:2). These female figures are cosmic and formal: the stereotyped extremes of femininity as seen by men. Blake’s defenceless Woman is an heir of this polarity. We would ourselves, I think, look in the ‘chambers’ of our brain (in Blake’s phrase) for a different cast of symbols.

Blake’s indivisible imagination and action have made him an icon of the political artist and visionary. He even took part in the Gordon Riots of 1780. Well, yes, he did; but only by mistake. His heroism lay elsewhere: in an indomitable spirit. Many of us may hope to see the world with Blake’s intensity. ‘If the doors of perception were cleansed’, Blake wrote, ‘every thing would appear to man as it is: infinite’ (Blake 2008: 39). So it does, in Revelation. But how in practice are we to relate Revelation’s phantasmagorical splendours to any present calling to re-conceive and liberate the world?

Blake demands that we open our eyes and see. We may not, in the end, see what he saw. But we will no longer be able to deny the grandeur and—sometimes terrifying—appeal of the powers around us and within us. Blake saw more in the heavens than most of us ever will. ‘What it will be Questioned’, he asked, ‘when the Sun rises do you not see a round Disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea O no no I see an Innumerable company of the Heavenly host crying Holy Holy Holy is the Lord God Almighty’ (Blake 2008: 555–6).

References

Blake, William. 1956. The Letters of William Blake, ed. by Geoffrey Keynes (New York: Macmillan)

———. 2008. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. by David V. Erdman and Harold Bloom (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press)

Sandro Botticelli :

'Mystic Nativity', 1500 , Oil on canvas

Diego Velázquez :

The Immaculate Conception, 1618–19 , Oil on canvas

William Blake :

The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun (Rev 12:1–4), c.1803–05 , Black ink and watercolour over traces of graphite and incised lines

‘Immortal Eyes and Eternal Worlds’

Comparative commentary by Robin Griffith-Jones

‘The Imagination’, wrote William Blake, ‘is not a State: it is the Human Existence itself’ (Blake 2008: 32). Revelation fires the imagination of artists, and should fire our own. We can, of course, think, hope, and dream only in the terms of our own age. Some terms have carried through the centuries; others have faded.

For Augustine (354–430 CE) and thence the whole Western Church, the miasma of original sin and its guilt was ineluctably transmitted through sexual generation: ‘in sin did my mother conceive me’ (Psalm 51:5). Jesus himself had of course been conceived without sexual congress; and he was wholly sinless. And Mary? Could she—must she—have been free from any such taint herself, in order to have been deemed or made worthy to be the Mother of God? In that case, she surely needed no redemption by her Son: such a claim was either outrageous or glorious.

The Spain of Diego Velázquez saw in Revelation 12 an icon of Mary’s Immaculate Conception. The doctrine became Roman Catholic dogma only in 1854; but it had been a point of fervent belief—and bitter dispute—since the Middle Ages. The Dominicans opposed it; the Franciscans extolled it. When in 1617, to try again to end the disputes, a papal Bull forbade any censure of the doctrine, there was celebration throughout Andalusia, ‘the land of Mary most Blessed’, and in its principal city Seville.

Velázquez portrayed an ancient vision brought newly to life for the Carmelites of Seville and still alive throughout Catholic Christendom to this day.

And Sandro Botticelli’s Mystic Nativity? This painting, seemingly so simple, encodes more mysteries than we have yet seen. According to its inscription, the devil will be bound in chapter 12 of Revelation. But not so. He will be bound far later in the book, at its climax (Revelation 20:2), before the 1,000 years of Christ’s first reign. The devil will then be released for the final battle, defeated, and cast forever into the lake of fire (Revelation 20:4–10). Botticelli seems to have wrenched the final battle out of its setting and brought it forward to the first Christmas.

Botticelli is following a long tradition here. Augustine himself had said that the climactic events of Revelation 20 started with the binding of the devil at Christ’s nativity, when the devil’s power was first curbed (City of God 20.7–8).

Revelation divides naturally into seven sections, which may either describe seven successive phases in the history of creation, or recapitulate the whole of that history seven times with the emphasis in each reprise moving onwards, over the series, from primordial history to the end of this present world. From Augustine onwards, no exegete could completely escape the sense of recapitulations. But it was still possible—and important—to locate one’s own time in God’s plan. The Florentine friar Savonarola declared that he was living in the fourth of the successive phases, described from Revelation 11:19.

And so back to Botticelli’s Mystic Nativity: the story told in Revelation 12 encapsulates the whole history of salvation. Here in the Nativity is Christ’s first coming and the devil’s first defeat (Revelation 20:2). Here too, in the vast timeline of history, is its turbulent fourth phase, in the Florence of 1501 in which Botticelli is painting (Revelation 11:19 onwards). And this augurs and even inaugurates the devil’s final release, defeat, and eternal imprisonment (Revelation 20:4–10) in those devils running for cover

Savonarola spoke fervently of Christ coming to Florence as he had to Jerusalem. The Nativity invites us, conversely, to take our own initiative and come to Christ: to walk that winding path into the painting to join the worshippers and angels at the crib. Then indeed Christ will be with us again, the devil will be bound, and mercy and truth will kiss each other. Botticelli unveiled in this Nativity on earth all the significance of the signs in heaven: the Woman and her Child, the beast from the abyss, and the war in heaven. Those who have eyes to see all salvation distilled into one such scene, let them see.

There were and are many forms of vision. It is hard to know what significance—let alone what authority—to grant to any of them. William Blake’s watercolour is enthralling, but does not interpret itself. If we are not careful, it might become an art-historical diversion, just an aesthete’s delight. So too, we can reduce Revelation itself to a literary and historical jigsaw.

That would be a sad diminution, of our text and our images alike. But what are the responsible alternatives? Most of us are not visionaries, and we help nobody by pretending we might be. But our three images make an offer: that despite all our caveats we can cleanse the doors of our perception and in our imaginations discern something of the animated, personal glory of God’s Wisdom at work in our own turbulent times.

References

Augustine. 2008. The City of God (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers)

Blake, William. 2008. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. by David V. Erdman and Harold Bloom (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press)

Commentaries by Robin Griffith-Jones