Revelation 4:1–11

God’s Throne Room

Dame Elisabeth Frink

Eagle Lectern, 1962, bronze with a dark brown patina and salvaged stone base, 147.3 cm high, Location unknown; ©️ 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London; Photo: ©️ Christie's Images / Bridgeman Images

Bearing the Weight of the Word

Commentary by Richard Stemp

After the medieval building had been reduced to a ruined shell by enemy bombing during the Second World War, architect Basil Spence wrote an account of the rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral. When talking about the design of the pulpit, he concluded that ‘the lectern had to have the traditional Eagle’. He then went on to say, ‘Elisabeth Frink, that gifted sculptress, was to my mind an obvious choice. She designed and carried out a magnificent bird which looks as if it had just settled here after a long flight’ (Spence 1962: 104).

But why was the Eagle ‘traditional’?

The answer comes, in part, from Revelation 4:6–7, and the ‘four living creatures’ which echo those seen by Ezekiel in Ezekiel 1 and 10. In Against Heresies, written around 180 CE, Irenaeus interpreted them as representing the four Evangelists, and the Eagle was identified as John (Against Heresies 3.11.8).

John’s Gospel famously opens with the statement, ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God’ (John 1:1). Although John mentions his namesake, John the Baptist, as one who ‘came…to bear witness to the light’ (John 1:7), the Evangelist too bears witness to the Word through his Gospel—and so it makes sense that his symbol, the Eagle, should bear the weight of the word.

Frink’s sculpture is thus a practical object, a vital piece of church furniture, as well as being a work of art. Spence’s realization that she was an ‘obvious choice’ to make the work acknowledged her early success—she was twenty-eight—but arose more specifically from her sculptures of tortured, angular birds, a series in which she captured something of her own experience of the war. On one occasion, she had narrowly avoided death when a German fighter machine-gunned the precise location where she and her friends had just been playing. As Frink herself said, ‘It’s to do with birds flying, planes crashing—big monstrous things flying, sometimes with a man in them’ (Spalding 2013: 12).

Frink’s lectern, however, is not one of these tortured, injured creatures, but, with its enormous wingspan—more than a metre—and the firm grasp of the talons, it is a creature that demands attention, and speaks with authority.

References

Porter, William. 2018. ‘Lot Essay: Dame Elisabeth Frink, R.A. (1930–1993) Eagle Lectern’, www.christies.com, available at https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-dame-elisabeth-frink-ra-1930-1993-eagle-lectern-6175152/ [accessed 10 September 2022]

Spalding, Julian. 2013. ‘Frink: Catching the Nature of Life’, in Elisabeth Frink: catalogue raisonné of sculpture 1947–93, ed. by Annette Ratuszniak (London: Lund Humphries), pp. 9–23

Spence, Basil. 1962. Phoenix at Coventry: The Building of a Cathedral (London: Geoffrey Bles)

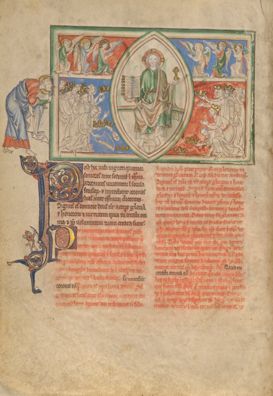

Unknown artist, England

The Twenty-Four Elders Pay Homage to the Throne of God, c.1255–60, Tempera, gold leaf, coloured washes, pen and ink on parchment, 31.9 x 22.5 cm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Ms. Ludwig III 1 (83.MC.72), fol. 4v, Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program

Embodying the Vision

Commentary by Richard Stemp

In the centre of this illumination, Christ sits enthroned upon a rainbow of which the most prominent colour is green, ‘like an emerald’ (Revelation 4:3). Although there is also an arc of red, the green predominates, in part due to the choice of the same colour for his robe.

Christ is framed by a mandorla, the name taken from the Italian word for ‘almond’, coloured in the same way. (Revelation 4:3 describes the rainbow as being ‘around the throne’.) Three angels kneel in adoration on either side of the mandorla’s top, and below them we see the twenty-four elders as they ‘fall down … and worship him,’ and ‘cast their crowns before the throne, singing’ (v.10).

Folio 4v of the Getty Apocalypse is specifically an illustration of Revelation 4:10–11. Many other details described in Revelation 4 are not included, but that is simply because another illumination, on folio 3v of the same manuscript, covers everything else. Both images include a haloed figure peering through a window in what appears to be the frame of the picture. This is the author of Revelation, traditionally identified as St John the Evangelist.

The unknown artist includes John to communicate the visionary nature of Revelation, as we see him ‘seeing’. In the first verse of the chapter, John mentions ‘in heaven an open door’—and it is through this that, ‘in the spirit’ (v.2), John witnesses the scene.

However, the ‘door’ is positioned differently in each image. On folio 3v, it is higher—at a level with Christ’s eyes—and John stands upright to peer through it. In this way, his stance echoes those of the elders, sitting upright on their thrones.

Here, the door is lower, so that the author bends to see through it, again echoing the elders as they prostrate themselves before the throne.

In these ways, the vision is shown to be an embodied one, with visual clues being given to the reader to help them to understand, and to remember, the actions of the text.

References

Lewis, Suzanne. 1992. ‘Beyond the Frame: Marginal Figures and Historiated Initials in the Getty Apocalypse’, The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal, 20: 53–76

Morgan, Nigel. 2012. Illuminating the End of Time: The Getty Apocalypse Manuscript (Los Angeles: Getty Publications)

Gabriel Dawe

Plexus A1, 2015, Thread, painted wood, and hooks, 7.62 x 3.65 x 12.19 m, Site specific installation at the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Renwick Gallery; Courtesy of Talley Dunn Gallery; Photo: Ron Blunt

Closer to the Transcendent

Commentary by Richard Stemp

There can be something magical about seeing a rainbow. This is surely because we are looking at something that is not there, a trick of the light, which—coming from behind us, refracted and reflected through droplets of water—allows us to see its different colours. However, Gabriel Dawe’s Plexus A1 is a double bluff, the illusion of a rainbow, created by solid matter—seemingly endless lengths of coloured thread. The immaterial is revealed to us as reality.

As Dawe himself says, ‘When you see a rainbow in nature you get a glimpse of the order that exists behind nature’ (Ault 2015). While he is referring to the laws of physics, the way in which the visible rainbow reveals these invisible truths parallels John’s vision of heavenly truth as it is manifested in our visible world.

Plexus A1 was created for an exhibition at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Museum in Washington DC in 2015. The exhibition was entitled Wonder—and a response of wonder is elicited by the sheer scale of Dawe’s work. In some ways, such a response is analogous to that inspired by the description of the heavenly throne in Revelation, which evokes the splendour of precious gemstones, the sublime terror of lightning, and the ‘magic’ of the rainbow.

Dawe’s installation is one of a series that takes its title, Plexus, from the network of nerves, blood, and lymph vessels which link the various parts of the human body. According to the artist, the title further refers ‘to the connection of the body with its environment. It also relates directly to the intricate network of threads forming the installation itself’ (Dawe ‘Density’).

Dawe believes that too many people are unaware of our interdependence with nature, and as a result are in danger of ‘killing everything into the ground’ (Ault 2015). There is an increasing fear that the world as we know it will end as a result of climate change, and humankind’s own actions.

Revelation’s rainbow throne (in its echo of Genesis 9’s rainbow) offers a sign of promise even in the face of impending destruction.

With the ‘wonder’ of Plexus A1, Dawe hopes to ‘offer the viewer an approximation of things otherwise inaccessible to us—a glimmer of hope that brings us closer to the transcendent, to show that there can be beauty in this messed up world we live in’ (Dawe ‘Density’).

References

Ault, Alicia. 2015. ‘Artist Gabriel Dawe Made a Rainbow Out of 60 Miles of Thread, 17 November 2015’, www.smithsonianmag.com, [accessed 28 May 2023]

Dawe, Gabriel. n.d. ‘The Density of Light’, www.gabrieldawe.com [accessed 30 May 2023]

Dame Elisabeth Frink :

Eagle Lectern, 1962 , bronze with a dark brown patina and salvaged stone base

Unknown artist, England :

The Twenty-Four Elders Pay Homage to the Throne of God, c.1255–60 , Tempera, gold leaf, coloured washes, pen and ink on parchment

Gabriel Dawe :

Plexus A1, 2015 , Thread, painted wood, and hooks

Islands and the End of the World

Comparative commentary by Richard Stemp

Revelation has long been accepted as a text that presents unique interpretative challenges. Jerome (d. 420 CE) observed that ‘manifold meanings lie hidden in its every word’ (Letter 53: 9). A millennium afterwards, Martin Luther was initially sceptical about its value, claiming that it was ‘neither apostolic nor prophetic’, and even that ‘Christ is neither taught nor known in it’ (Luther 1522: 398). Only later did he relax his stance, suggesting that one ‘ought to read this book…with other eyes than those of reason’ (Luther 1530: 410).

In many respects it is a book that defies logic. But then, logic is part of the structures of normal, everyday human experience, and the sudden, visionary appearance on earth of heavenly truths often requires the overturning of such structures. The reader is, therefore, invited on an interpretative journey through metaphor, allusion, and subtle negotiations of possible meaning. Christopher Rowland notes that Tyconius, writing in the same period as Jerome, saw Revelation as ‘having a contemporary application to the life of Christians living in the midst of ambiguity’ (Rowland 2016: 6). That is just the condition in which so many find themselves today, especially as more and more people fear for the future of the planet.

There is ambiguity, too, about the authorship of the commentary whose words appear alongside the biblical text in the Getty Apocalypse. It is usually attributed to Berengaudus, an obscure figure thought to have lived in either the ninth or eleventh century.

Berengaudus follows one of the most common interpretations of the ‘open door’ in Heaven (4:1): that it represents Jesus himself, in line with John 10:9, ‘ I am the door’. The anonymous illuminator seems to use this idea, and the door becomes a ‘viewfinder’, which thus accentuates the point that we are witnessing a vision. Berengaudus interprets the rainbow as representing ‘the Church, which surrounds us with its mercy,’ and ‘protects, governs, and defends us against invisible enemies’ (Morgan 2012: 41).

Two of the three artworks here, like the text itself, can be described as ‘insular’, whether because they explore what it is to feel threatened in a small space, or because they communicate insights that have been arrived at in places relatively cut off from the rest of the world.

The traditional location of John’s Revelation was the island of Patmos, while the Getty Apocalypse was created in Britain, which, at the time the book was illuminated, was on the island fringes of European civilisation.

Elisabeth Frink grew up on the same island, at a time when the future of the world was very much in doubt. She made her name in the aftermath of the Second World War, and during the complex peace which followed. With the conclusion of the conflict through nuclear destruction, it was now clear that humankind had the ability to destroy itself and bring about the end of humanity even without divine intervention. Growing up on an island that had once commanded a global empire and was now watching it dwindle, her tortured figures and angular forms were associated by some with a contemporary style which Herbert Read dubbed ‘the geometry of fear’ (Spalding 2013: 13).

Gabriel Dawe might appear to be an exception. He grew up in Mexico and now lives and works in the United States—neither of which is particularly ‘insular’. However, his concerns are with our interconnectedness across the globe, which, in the age of space exploration increasingly came to seem like an island itself—tiny compared with the size of the galaxy as a whole, though providentially at the right distance from the sun to support life. His revelation of the laws underlying the natural order, of our connectedness one to another and to our wider environment, reminds us of our responsibility to ourselves and to the world around us.

Writing about colour field painting (and specifically Richard Anuszkiewicz’s Rocket Red Apex, 1969), Dawe remarks on how the scale of such painting ‘[elicits] a trance-like state’:

It is futile to resist, and it would be foolish to try to make sense of it with the mind. (Dawe, 2019)

Even if there is a certain logic underlying its construction, his own work invites a similar response. Coincidentally, he thus echoes Luther’s opinion about Revelation.

The Getty Apocalypse shows us John witnessing to his revelations, Frink’s Eagle Lectern bears the Bible which witnesses to God’s Word, while Dawe’s Plexus A1 gives us the chance to witness something for ourselves, and to find a sense of community in the process.

There is positive hope in this last event of witness which suggests that all is not—yet—lost. Perhaps in its own way it chimes with Revelation 4’s vision of the second coming of Christ, in which the end is revealed as a new beginning.

References

Dawe, Gabriel. 2019. ‘Experiencing Color Field Art’, in Seeing America: The Arc of Abstraction, by Tricia Laughlin Bloom (Newark, NJ: Newark Museum)

Luther, Martin. 1960 [1522]. ‘Preface to the Revelation of St John [1]’, in Luther’s Works, vol. 35, ed. by E. Theodore Bachman (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press), pp. 398–99

______. 1960 [1530]. ‘Preface to the Revelation of St John [2]’, in Luther’s Works, vol. 35, ed. by E. Theodore Bachman (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press), pp. 399–411

Morgan, Nigel. 2012. Illuminating the End of Time: The Getty Apocalypse Manuscript (Los Angeles: Getty Publications)

Rowland, Christopher. 2016. ‘The Reception of the Book of Revelation, An Overview’, in The Book of Revelation and its Interpreters: Short Studies and an Annotated Bibliography, ed. by Ian Boxall and Richard N. Tresley (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield), pp. 1–25

Schaff, Philip (ed.), W.H. Fremantle, G. Lewis, and W.G. Martley (trans.). 1893. The Letters of St Jerome, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series 2, vol. 6 (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co.)

Spalding, Julian. 2013. ‘Frink: Catching the Nature of Life’, in Elisabeth Frink: catalogue raisonné of sculpture 1947–93, ed. by Annette Ratuszniak (London: Lund Humphries), pp. 9–23

Commentaries by Richard Stemp