Romans 12:1–8

Be Transformed

Samuel Palmer

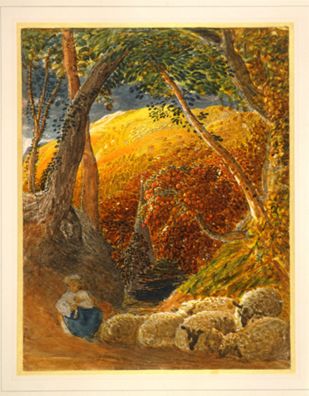

The Magic Apple Tree, c.1830, Pen and Indian ink, watercolour, in places mixed with a gum-like medium, on paper, 349 x 273 mm, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; Given by A.E. Anderson in memory of his brother, Frank, 1928, 1490, © Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge / Art Resource, NY

Fruitfulness and Transfiguration

Commentary by Malcolm Guite

The key word in the opening verse of Romans 12 is ‘Therefore’ (Greek: oun). Paul’s appeal for transformation here is a glad and free response to ‘the mercies of God’ as set out in the previous chapters of the letter, but especially the eleventh. Using the image of a tree, which receives the graft of a new branch (the Gentiles), Paul sees us all as rooted and grounded in universal mercy: ‘he has concluded all under sin that he might have mercy on all’ (Romans 11:32). Romans 12:1–8 is a call to respond to unmerited and unconditional grace, to ‘mercies’ already freely given and received, a call to let that mercy bear fruit.

Fruitfulness and transfiguration are central to Samuel Palmer’s painting The Magic Apple Tree, especially, at the heart of the painting, the apple tree itself, bowing its branches low and offering its fruit freely to all, in a more than natural abundance, itself suggestive of grace.

The painting is from his ‘Shoreham Period’, painted in the place in Kent he called ‘the valley of vision’ (Wilcox 2005: 29–42). Together with the other ‘Ancients’, a fellowship of Christian visionary artists all inspired by William Blake (1757–1827), Palmer was seeking, even in the shadow of the Fall, to paint a vision of the world redeemed by grace, to see things in the light of Eden, rather than in its shadows. The golden light which shines beneath, rather than beyond the dark storm clouds above it, so that it gilds the corn and lights the apples, hints at a revelation of glory in and through creation, rather than simply above and beyond it, something also hinted at in Paul’s phrase ‘For from him and through him and to him are all things’ (Romans 11:36).

The shepherdess in the foreground, and the church spire at the centre of the composition, establish both a pastoral and Christian context for the scene, but it is the tree itself that draws us in to grace and restoration.

References

Wilcox, Timothy. 2005. Samuel Palmer (London: Tate)

David Jones

Flora in Calix Light, 1950, Graphite and watercolour on paper, 570 x 768 mm, Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge; DJ 5, © Estate of David Jones / Bridgeman Images; Photo: © Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge / Anthony Hynes 2010

Things Are More Than They Are

Commentary by Malcolm Guite

‘Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds’. These words from Romans 12:2 get to the heart of the passage: in the light of grace, the world is not to be annihilated but transformed, so that the glory of the redeemed may be revealed. With its numinous fullness, David Jones’s watercolour of three translucent glass chalices (Latin: calix) on a table by an open window amidst a plethora of flowers may help us to imagine such a transformation.

Jones was influenced by the works of French Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain (1882–1973), and had absorbed his Thomistic insight that ‘things are more than they are and they give more than they have’ (Williams 2005: 60–1). The insight was essential to his whole way of seeing the world and of being an artist. In Flora in Calix Light everything, down to the smallest detail, is abundantly ‘more than it is’ and ‘gives more than it has’.

There is here a sense of sheer pleroma, of overflowing and undeserved abundance. In Anne Price-Owen’s (2010) words, ‘Calyx is [both] the flower’s cup and Eucharistic chalice’. This table is also an altar. And it seems that everything at this altar flowers and is fulfilled. Even inanimate things, like the curling metal spiral of the window latch—seem to have come to life, and to be curling and growing like the tendrils of some vine. The window itself, partially open, seems to beckon, drawing the eye to go through and beyond the panes of ordinary sight. The effect is further enhanced by Jones’s curious double perspective: we see the three chalices as though we approached them to receive the sacrament, and yet we also look down on the whole table/altar, as though we ourselves might be standing there to make a consecration, and scattered on that surface we see the little ears of wheat that form the other element of the sacrament.

All of it is waiting, not to be conformed, but to be transformed.

References

Price-Owen, Anne. 2010. ‘Materializing the Immaterial: David Jones: Painter-Poet’, www.flashpointmag.com, 13, available at http://www.flashpointmag.com/priceowen.htm

Williams, Rowan. 2005. Grace and Necessity: Reflections on Art and Love (London: Bloomsbury Publishing)

Samuel Palmer

Coming from Evening Church, 1830, Tempera, chalk, gold, ink, and graphite on gesso on paper, 302 x 200 mm, Tate; Purchased 1922, N03697, © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Presented and Re-presented

Commentary by Malcolm Guite

Romans 12 moves from a contemplation of God’s mercies, through a call to transfiguration, to a consideration, beginning here in verses 6–8, of the church itself as a transformed community of grace.

In this painting, the church is central both to Palmer’s composition and its meaning. The spire of the church, exaggerated and elongated for effect, sets and guides the strong vertical lines that dominate the composition. Palmer disregards naturalistic conventions of proportion and perspective, suggesting instead that the order of nature has been transformed so as to conform to the order of grace. The hills have a peculiarly distorted steepness that is echoed in the cone-shaped gables of the buildings; the boughs form a natural arch; the trees and bushes take forms that echo the church’s architecture. All are transfigured in the numinous glimmering moonlight.

But arguably more significant than either the natural or architectural beauties are the people. Again Palmer shuns naturalism in order to suggest instead what is spiritually significant. Though they are painted in detail and variety, painted in their place and context, there is an archaic quality about them that means they seem to transcend any single historical moment. Young and old together, they are individual in their forms but—together—they constitute a single arc from the recesses of the painting to its foreground. They are in deep organic sympathy with the larger composition.

It seems a significant decision that the congregation is represented coming from the church rather than going into it. Having ‘presented their bodies as a living sacrifice’ (Romans 12:1), these figures are now re-presented to the world as a spiritual body, united in Christ and yet all the more clearly manifesting their integrated differences. Paul speaks of the different gifts given ‘in proportion’ to faith (Romans 12:6), and Palmer’s remaking of both proportion and perspective in this painting may help us to imagine, to glimpse in an outward and visible form the inward transformation of perspective, and the sanctification of the body itself which is bestowed in worship and is part of the transformation so central to this passage in Romans.

Samuel Palmer :

The Magic Apple Tree, c.1830 , Pen and Indian ink, watercolour, in places mixed with a gum-like medium, on paper

David Jones :

Flora in Calix Light, 1950 , Graphite and watercolour on paper

Samuel Palmer :

Coming from Evening Church, 1830 , Tempera, chalk, gold, ink, and graphite on gesso on paper

Unfolding a Triptych

Comparative commentary by Malcolm Guite

One way of allowing these three artworks to converse imaginatively with Romans 12:1–8 is to think of them as a triptych, and in particular as an altarpiece. To imagine these three works located at the place where we ‘present our bodies as a living sacrifice’ (12:1), the place where all things, both people and ‘these thy creatures of bread and wine’ (Book of Common Prayer) are presented so that they may no longer be conformed to this world, but rather transformed and renewed. If we were to unfold this triptych on our imaginary altar, David Jones’s Flora in Calix Light might be the central panel. Samuel Palmer’s The Magic Apple Tree could unfold to the left of it, with his Coming from Evening Church to the right.

So, centrally, we would see in the three glass chalices with their abundance of flora, their translucency, and their constant invitation to see through and beyond them, an icon of the mystery of transformation itself. The vases, the flowers, the window, the distant tree, even the table, are all of ‘this world’, as are the elements we might place on the altar and the people who come to receive them, but all are here transformed, transfigured. In and through these chalices we see, as Anne Price-Owen has observed, ‘Crucifixion and Resurrection’, ‘the mercies of God’ to which Paul is making his appeal in Romans 12:

…the three crystal glasses reference the crosses on Calvary. … Light, signifier of epiphany, and flowers, tremble and clamber over the whole picture, infiltrating it with divine beneficence. (Price-Owen 2010)

Viewed as a triptych in this way, we can then see the ‘calix-light’, the light of transformative grace, flowing from the central scene into the two on either side. On the left, in The Magic Apple Tree we see nature transfigured, a shadowed world seen for a moment in the light of Eden:

These colours seem to fall from Eden’s light,

The air they shine through breathes a change in them,

Breaking their sheen into a certain shade

Particular and unrepeatable.

Some golden essence seems to concentrate

From light to air, from pigment into paint

In increments of incarnation down

To burn within these apples and this bough…

(Guite, ‘The Magic Apple Tree’)

But this is no mere aesthetic transformation, the church spire, the shepherdess and sheep, and the paradisal tree all locate that transformation within the salvation story.

As we look from the central image (Jones’s chalices) to the right, we see the ‘calix light’ of Eucharistic grace informing the moonlight of Palmer’s painting and the redeemed community leaving the altar, themselves transformed, and ready to discern and work that same transformation in the world. Coming from worship, the procession that winds towards us seems transfigured, giving as much light to the scene as they themselves receive from the moon.

We can also read our triptych sequentially, moving through the pictures as through the Romans passage, beginning with The Magic Apple Tree as an image of ‘the mercies of God’ (v.1) then looking at Flora in Calix Light as both the locus in which we ‘present our bodies’ (v.1) and the place in which we move from being conformed to being transformed (v.2), and finally turning to Coming from Evening Church as showing us the ‘one body’ all ‘members of one another’ in movement and action (vv.3–8).

References

Guite, Malcolm. 2012. ‘The Magic Apple Tree’ in The Singing Bowl (London: Canterbury Press Norwich), p. 20

Price-Owen, Anne. 2010. ‘Materializing the Immaterial: David Jones: Painter-Poet’, www.flashpointmag.com, 13, available at http://www.flashpointmag.com/priceowen.htm

Commentaries by Malcolm Guite