Numbers 11

Graves of Craving

Antony Gormley

Home of the Heart II, 1992, Concrete, 85 x 36 x 49 cm; © Antony Gormley; Photo courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery

The Burden of Flesh

Commentary by Jonathan Parker

Antony Gormley’s Home of the Heart II helps us consider Moses’s complaint (Numbers 11:10–17; 24–30) about his task to ‘carry … this people alone’ (v.14).

Gormley’s sculpture is part of a series in which concrete blocks upon closer inspection reveal carefully placed holes through which the head and limbs of a body might pass.

Two aspects of this work help illuminate our text.

First, it contrasts the weightlessness of the body-shaped ‘interior’ with the heaviness of the block ‘containing’ it. Moses needs help in ‘lifting’ his ‘burden’ (vv. 11, 14, 17), and this sculpture can be read as a visualization of the demands of embodied life. Embodied humans have wants, desires, and needs—these all on a daily basis.

This sense of bodily burden can be additionally intense for those who, like Moses, are ‘caretakers’ of their fellow human beings: those with duties of protection and pastoral care. For them even more than for others, life can feel like being encased in a concrete block, not just of one’s own bodily needs but of others’ as well.

In addition to the weightiness of physical burdens, this sculpture captures the depth of Moses’s psychological state too. He has nothing left; he is, emotionally, ‘flat on his back’. Although Moses’s emotional burden is featured in other stories about him (cf. Deuteronomy 1:9–18; Exodus 18:13–27), only here is Moses in utter despair—to the point where he wishes to die (v.15; cf. 1 Kings 19:4). Under the weight of his current life, Moses just wants to lie down, forever. Some have thought this culpable, but Martin Luther displays the sympathy of a fellow pastor: ‘[O]nly speculative theologians’ would condemn him (Luther 1967: 30–31).

The supine state of Gormley’s block is all the more poignant when one also considers the threat that Moses’s death poses to the people he leads. If Moses dies, does their access to the word of God die with him? His personal cry for death signals a corporate cry of crisis.

Yet this cry will not be the end of the story, and Moses’s unique apprehension of the Lord (cf. Deuteronomy 34) will be carried forward to generation after generation—we are as much his audience as those he led through the wilderness. The particular, spiritual ‘holes’ in Moses’s particular, fleshly ‘block’ will be addressed by God’s particular, spiritual gift.

References

Luther, Martin. 1967. Luther’s Works, Vol. 54: Table Talk, ed. and trans. by Theodore G. Tappert (Philadelphia: Fortress)

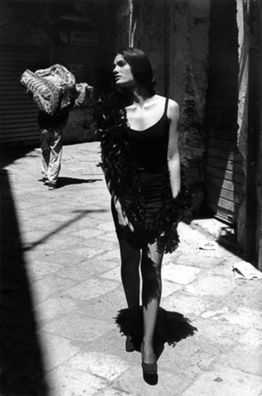

Ferdinando Scianna

Sicily, Palermo, 1991, Photograph; © Ferdinando Scianna / Magnum Photos

A Strong Craving

Commentary by Jonathan Parker

This photograph might be called merely ‘fashion art’, but, here and elsewhere, Ferdinando Scianna chooses to juxtapose his model with episodes of everyday life. Contrasts of life and death, of poverty and wealth, fill his ‘fashion’ portfolio; here, a model and (being carried in the background) a huge side of meat!

What is our attention drawn to here, and why? Are we drawn to the youth and beauty and clothing of the model or are we drawn to the meat? Are we provoked by envy or sexual desire or driven by hunger? What does the difficulty in untangling these possible responses tell us about the tangle of desires inside us?

Likewise, the desire for meat in Numbers 11 presents to us not just our hunger but our taste, not just needed nourishment (which is met by the manna, vv.7–9) but desired satiation (vv.4–6). The ‘strong craving’ of the ‘rabble’ in verse 4 (followed soon after by the rest of the people in v.10) signifies the transition from grateful partaking to avarice, the transgression of the limit that keeps enough from becoming too much.

God never rebukes the people merely for wanting meat. He rebukes them for letting their want for meat push them into rejecting Him as their saviour and rescuer from Egypt (vv.18b, 20b).

Although the Lord gives them what they want in abundance (vv.31–32; Psalm 78:27–29), the people were told to consecrate themselves (v.18), to prepare to be grateful. There is no indication they ever did or were. Instead, they consume the meat without gratitude or thankfulness. They may even have succumbed animalistically to devouring the flesh without cooking it. Verse 32’s ‘they spread them out’ implies ‘that they ate the meat raw’ (Milgrom 1989: 92). So ‘while the meat was still between their teeth’, God sent ‘a very great plague’ (v.33 NRSV), killing ‘the strongest of them’ (Psalm 78:31).

Scianna’s photo can help to draw out this aspect of Numbers 11. As in Numbers 11, death intrudes into the picture. Looking anew at the passage and the photo together, do we see something attractive (the desire for variety in food, the glamourous model) or how ugly and debased our cravings for ‘more’ can be?

References

Davis, Ellen. 2001. ‘Greed and Prophecy: Numbers 11’, in Getting Involved with God: Rediscovering the Old Testament (Lanham, MD: Cowley), pp. 202–08

Milgrom, Jacob. 1989. Numbers, JPS Torah Commentary (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America)

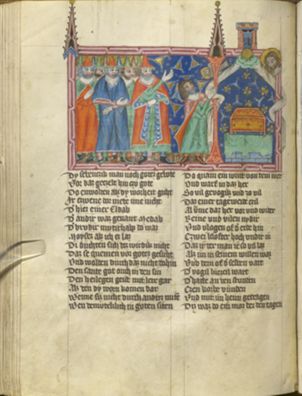

Unknown Bohemian artist

The Seventy Elders, from Rudolph von Ems Weltchronik, c.1360, Manuscript illumination, 295 x 220 mm, Fulda University and State Library (FUSL); 100 Aa88, fol. 124v, Fulda University and State Library (https://fuldig.hs-fulda.de/viewer/image/PPN314753796/)

Moses and the Seventy Elders

Commentary by Jonathan Parker

In the mid-1200s, Rudolph von Ems, a German knight and poet, composed the Weltchronik (‘Chronicle of the World’), consisting of ‘some thirty-three thousand lines of rhymed German verse’ (Cohen 1997: 67).

This copy of Von Ems’s seminal work was made for the accession of Charles IV to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire in 1355—bolstering the divine legitimacy of Charles’s new earthly authority by casting the empire itself as successor to the nation of Israel.

Numbers 11 (vv.16–17, 24b–25) is similarly concerned with the handing on of power: seventy elders are appointed to transmit Moses’s authority to future generations. The decorative architectural details depicted in this illumination of the episode mimic those atop the flying buttresses of St Vitus Cathedral in Prague. Moses obeys the Lord’s specific instruction to bring these elders ‘to the tent of meeting’ (cf. Exodus 33:7–11; 40:34–35). What better cultural equivalent to Moses’s tent of meeting than Prague’s St Vitus Cathedral? Here, we are dealing with the transfer of authority from Davidic Jerusalem to Carolingian Prague and from Moses to the later Christian Church.

The illumination deliberately includes God the Father as a golden circle on a ‘cloud’ (v.25) positioned above the centre of the tent of meeting, with God the Son (a second circle of gold haloing his human face) and the dove of God the Spirit to right and left, respectively. These bring a Christian hermeneutic to the scene. If the golden motifs in the illumination are read as signalling God’s presence and activity, it is striking that the symbols of the Spirit’s progress which we see outside the tent of meeting are a different shape from those representing the divine activity within. Forming triangles like Moses’s (falling) cone-shaped Jewish hat, these golden motifs seem to move from the Spirit via Moses to form a golden aura over the heads of the elders. Here is a specific equipping of scribes (or ‘officers’) and ‘elders of Israel’ (v.16) to prophesy like, with, and from Moses (v.24). They will carry his authority (‘the spirit upon Moses’) beyond his foretold death and into the future.

The depiction of this centralized, authoritative, prophetic but conciliar body receiving Moses’s spirit opens a theological path of continuity to the way that the spirit of Christ’s own person is breathed onto his disciples (John 20:22; cf. Luke 10:1–12, and Acts 2:1–13).

References

Cohen, Aaron S. 1997. ‘Rudolph von Ems, Weltchronik’, Masterpieces of the J. Paul Getty Museum: Illuminated Manuscripts (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum)

Mengel, David C. 2004. ‘From Venice to Jerusalem and Beyond: Milíč of Kroměříž and the Topography of Prostitution in Fourteenth-Century Prague’, Speculum 79: 407–42

———. 2014. ‘Emperor Charles IV, Jews, and Urban Space’ in Christianity and Culture in the Middle Ages: Essays to Honor John Van Engen, ed. by David C. Mengel and Lisa Wolverton (Notre Dame, IL: University of Notre Dame Press)

Roth, Norman. 2014. Medieval Jewish Civilization: An Encyclopedia (Hoboken, NJ: Taylor & Francis)

St Clair, Archer. 1987. ‘A New Moses: Typological Iconography in the Moutier-Grandval Bible Illustrations of Exodus’, Gesta 26: 19–28

Antony Gormley :

Home of the Heart II, 1992 , Concrete

Ferdinando Scianna :

Sicily, Palermo, 1991 , Photograph

Unknown Bohemian artist :

The Seventy Elders, from Rudolph von Ems Weltchronik, c.1360 , Manuscript illumination

Gifts of God for the People of God

Comparative commentary by Jonathan Parker

Ferdinando Scianna’s photo can work to unmask us; to present us with ‘our selves, our souls and bodies’. We are not, in fact, ‘reasonable, holy, and living sacrifices’ to the Lord (BCP 1979: 336). We are full of desires, brimming to the point of cravings and boiling to the point of lust, envy, and covetousness.

The ‘quail story’ of Numbers 11 performs a similar service for us, reminding us that, more often than not, our wants are not our needs but rather wanton desires that obscure the divine Giver. But what do these desires have to do with the rest of this biblical chapter—especially with the story of the elders whose prophesying seems ill-equipped to help with something as basic as hunger for meat? ‘How [the relief of Moses’s burden] is achieved by putting the seventy elders into a state of ecstasy is difficult to imagine’ (Noth 1968: 89).

It may be difficult to imagine, but not impossible. In all likelihood, the passage is an extended meditation on the Hebrew word, massa (which can mean both ‘burden’ and ‘oracle’), and on the phrase ‘graves of craving’ (which is the meaning of the place name in v.34, Kivrot ha-Ta’avah). As we have seen, our cravings can themselves be burdens, not just to us, but to those who care for us. The response we need is the gifts of God by his ruach, which means both ‘breath’ and ‘spirit’ but also ‘wind’ as in verse 31 when God blows in more meat than is humanly imaginable. Coming on the heels of God’s gift of the spirit on the elders at the tent of meeting, as depicted in the von Ems illumination, we can soon see that the unity of God’s action is his overflowing gift (Olson 1996: 68–69).

It is this overwhelming gift which itself overcomes Moses’s overwhelming ‘burden’, transforming his view of himself as trapped and ‘as good as dead’ to a blessedly limited but viable conduit of the Spirit of God upon him. If Moses had been able to look at Antony Gormley’s sculpture, he might initially only have seen the weight with which his concrete flesh felt burdened, but after God’s address to him (vv.16–23), he might instead have seen divine air, wondrously passing through the ‘body’ whose imprinted form proves able to receive and channel it.

According to Numbers 11, our creaturely life does not just need the satisfaction of our wants but the sanctification of our desires. A spiritual process that can only take place in and through chosen, trustworthy, and yet fallible bodies, ‘sanctification is the act of God the Holy Spirit in hallowing creaturely processes … within the history of creation’ (Webster 2003: 17–18). Holy oracles interpret God’s material gifts through a gracious chain of fallible but sanctified authorities so that we might know how to live in our bodies.

Even if we often neglect such prophetic help, like the prophesying of the elders who seem to have no effect on the people’s greed, we are not compelled to see the gift itself as fruitless. Indeed, we may only be underestimating our own sin. Psalm 78 deals with Numbers 11 specifically and suggests that God graciously continues his sanctifying acts, until he gets our attention, ‘In spite of all this they still sinned; … so he made their days vanish like a breath, … [only] When he killed them, they sought for him; they repented and sought God earnestly’ (Psalm 78:31–34 NRSV).

According to Numbers 11, God’s gifts come despite our sin, simultaneously telling us the truth about ourselves, giving us more than what we need, and calling us to continue to listen to His Spirit in our midst, in the middle of our blessedly limited creaturely lives.

References

Book of Common Prayer. 1979. (New York: Seabury Press)

Noth, Martin. 1968. Numbers, trans. by James D. Martin, Old Testament Library (London, SCM)

Olson, Dennis T. 1996. Numbers, Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching (Louisville: John Knox Press)

Webster, John. 2003. Holy Scripture: A Dogmatic Sketch, Current Issues in Theology 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Commentaries by Jonathan Parker