2 Kings 5

The Healing of Naaman

Francis Frith

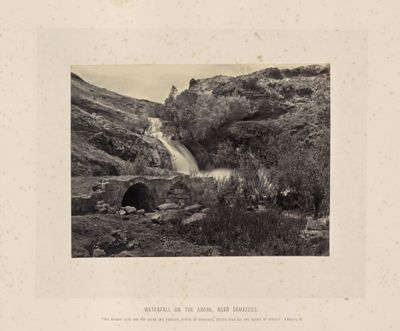

Waterfall on the Abana, near Damascus, c.1865, Albumen silver print, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; 84.XO.826.5.37, Image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program

Foreign Waters

Commentary by Stephen John Wright

In one of the most famous tantrums in the Bible, Naaman declares that he does not want to bathe in the waters of the Jordan. ‘Are not Abana and Pharpar, the rivers of Damascus, better than all the waters of Israel?’ (2 Kings 5:12). Anger comes to him at Elisha’s cold reception, which he directs towards the river he is instructed to bathe in. The entire project nearly comes undone, but for the intervention of his servants who keep him on track.

Francis Frith was a Victorian photographer, who became famous for his pictures of the biblical lands. This image is one of forty in a folio of images published in 1865 as F. Frith’s Photo-Pictures from the Lands of the Bible. Illustrated by Scripture Words. Whereas it was medieval practice to illuminate Scripture with images, Frith’s collection provides one of the earliest and most popular examples of illuminating photographs with Scripture. He trades on the apparent literalism of the photograph. Frith describes his desire to allow the viewer to vicariously witness the lands of the Bible through his lens (Van Haaften 1980: vii).

Taken near Damascus, in this photograph we observe a portion of the Abana forming a waterfall above a stone arch aqueduct. The water’s smooth surface, softened by the slow exposure time required by Frith’s techniques, places the water in sharp contrast with the rest of the photograph. Photography compresses time into a single image. The photograph renders the river anew.

Naaman desires the comfort of the familiar, but the God of Israel gives to him the new. To remain with the familiar would be to remain with old rivers and old diseases. Instead, the strange waters of Israel restore and renew. They enable the recognition of God’s identity. Just as the photograph renders a familiar landscape in a strange way, through the healing waters the believer sees the world in new ways.

References

Van Haaften, Julia. 1980. Egypt and the Holy Land in Historic Photographs: 77 Views by Francis Frith (New York: Dover Publications)

Rembrandt van Rijn

A man in Oriental Costume (King Uzziah Stricken by Leprosy), c.1639, Oil on panel, 103 x 79 cm, Chatsworth House Trust, Derbyshire; © The Devonshire Collections, Chatsworth; Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees / Bridgeman Images

Gehazi’s Kindred

Commentary by Stephen John Wright

Leviticus is oddly detailed when it comes to treating leprosy. ‘Leprosy’ in the Bible encompasses a range of contagious skin conditions. If one is to follow the Levitical laws, lepers are to tear their clothes, leave their hair dishevelled, and announce their corrupting presence by shouting ‘unclean, unclean!’ (Leviticus 13:45).

None of these features appears in Rembrandt van Rijn’s painting. His departure from the biblical conventions for identifying lepers suggests that something unusual is happening here. The image is a study in theodicy.

Rembrandt’s painting depicts a man identified only by his illness. The tightly knotted turban, the cloak draped over his shoulders joined at the chest by a golden and bejewelled fastening, and the sparsely adorned room behind him with a serpentine column, all fail to give much insight into his identity. The highlighted features of the man—his face, his hands—show the marks of his skin condition.

The ‘oriental’ style of the figure has led most scholars to attempt to place him within the world of Scripture. He has been identified as Moses, Aaron, Dan, Naaman, and most frequently in recent scholarship as King Uzziah (Boeckl 2011: 74).

Placed alongside 2 Kings 5, this painting becomes a commentary on affliction. The dark eyes set within the mottled face could be Naaman’s or Gehazi’s. The narrative of Naaman’s healing turns on the shock twist of Gehazi’s deception and punishment. His unrighteousness manifests as impurity. 2 Kings 5 reinforces the association of leprosy with sin.

Rembrandt shows that wealth cannot purify the heart. The pensive facial expression sets a limit on what can be seen, and provokes the viewer to imagine the unseen condition of the heart. We see a face marred not by skin disease, but regret. Whoever Rembrandt has depicted here is the kindred of Gehazi.

References

Boeckl, Christine M. 2011. Images of Leprosy: Disease, Religion and Politics in European Art (Kirksville: Truman State University Press)

Unknown South Netherlandish artist

Seven Scenes from the Story of the Seven Sacraments, Namaan Being Cleansed in the Jordan, c.1435–50, Tapestry, wool warp, wool and silk wefts, 231.1 x 208.3 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1907, 07.57.3, www.metmuseum.org

The Baptism of Naaman

Commentary by Stephen John Wright

Naaman never undergoes Christian baptism. Yet, when Naaman steps into the waters of the Jordan to be cleansed, Christians witness a prefiguration of their own baptisms. Immersed seven times, he arises with flesh ‘like that of a young boy’. Likened to a na’ar qaton, he is an analogue to the young Israelite girl, na’arah qetanah, who first directed him to Elisha (Brueggemann 2000: 33).

Depictions of Naaman’s baptism reached their high point in the medieval period, between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries (Boeckl 2011: 73), but here is a later example from the mid-fifteenth-century Netherlands. It is a panel from a larger tapestry depicting the seven sacraments along with Old Testament scenes intended to prefigure them. These biblical images provide visual commentary on the sacraments. The Old Testament scenes run horizontally along the top of the tapestry, with their sacramental counterparts beneath them, joined by a ‘scroll’ of text. The tapestry survives only in fragments, but the full tapestry would have been around 14 metres long and 4.8 metres high (Cavallo 1993: 160).

Naaman’s healing provides the tapestry’s commentary on baptism. We see him, already healed, in the waters of the Jordan, accompanied by two servants and Elisha. The viewer is invited to note the parallels between his healing and the baptism beneath him. His cleansed skin matches that of the child on the baptismal panel. The inclusion of Elisha, who was not present at the healing in the biblical text, suggests a priestly presence.

Only a portion of the scroll of text survives from this panel. We can read ‘… stories from scripture / … baptism purified / … washed in the Jordan’. Elisha does not follow the Levitical provisions for the management of skin diseases—examination, diagnosis, exclusion. Impurity creates isolation. By Elisha’s instruction, Naaman is instead purified. ‘Naaman’s story is the story of every baptized believer’ (Nelson 1987: 182).

References

Boeckl, Christine M. 2011. Images of Leprosy: Disease, Religion and Politics in European Art (Kirksville: Truman State University Press)

Brueggemann, Walter. 2000. 1 & 2 Kings (Macon: Smith and Helwys Publishing), pp. 331–40

Cavallo, Adolfo Salvatore. 1993. Medieval Tapestries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art), pp. 156–71

Nelson, Richard. 1987. First and Second Kings (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press), pp. 176–83

Francis Frith :

Waterfall on the Abana, near Damascus, c.1865 , Albumen silver print

Rembrandt van Rijn :

A man in Oriental Costume (King Uzziah Stricken by Leprosy), c.1639 , Oil on panel

Unknown South Netherlandish artist :

Seven Scenes from the Story of the Seven Sacraments, Namaan Being Cleansed in the Jordan, c.1435–50 , Tapestry, wool warp, wool and silk wefts

Foreign Purity

Comparative commentary by Stephen John Wright

For his bounty, the foreign general takes two mule-loads of soil. He arrives in Israel loaded with the fineries of gold, silver, and garments, but after his healing he values the dirt of the land more highly than all of this. The story of Naaman is touched by numerous such little ironies.

We are introduced to Naaman as the instrument of the LORD. It is a shock to discover that he also has leprosy, which typically signifies sin. The great general’s actions are directed by servants, who rescue him from ruin twice. The King of Israel tears his clothes and cries out, which are the actions required of lepers in Leviticus 13:45.

The most surprising twist, however, appears in the deception of Gehazi. In Gehazi we can locate one of the central issues of the Naaman story: foreignness. The servants of the foreign general are righteous, but the servant of the prophet of the LORD falls. Naaman’s leprosy is healed, and now attaches itself to Gehazi and his descendants. John Bunyan treats Gehazi as a precursor to Judas, but perhaps we also see something of Cain in him: desire for what another has, deception, and generational disease.

Gehazi only rarely appears in artistic renditions of this story. Yet there are two miracles in 2 Kings 5: the healing of Naaman, and the affliction of Gehazi (Nelson 1987: 176).

Rembrandt van Rijn’s image opens up space for us to consider the darker miracle. The relative anonymity of the figure renders the blotched and decrepit skin more concerning. Rembrandt’s stylized ‘oriental’ dress presents this man as a foreigner. The meaning of the painting is not readily disclosed to the viewer. His expression is closed, eyes glazed over by the sorrow of reflection. Uzziah and Gehazi both stand as figures who attempted to grasp what was not theirs to have. The pensive face, in this light, serves as a study in unintended consequences. For a people who associate wealth with happiness, the marriage of opulent dress with a grave and diseased face distresses our arrangement of the world.

Namaan’s story also turns on misdirected desire for foreign comforts. He considered himself to be deserving of special attention and treatment, due to his status. He came with gifts typical of a state visit, carrying a letter of introduction from his king to the king of Israel. His self-importance nearly undoes the entire enterprise. Francis Frith’s image of the Abana depicts a simple waterfall set in rugged surrounds. One might wonder what the fuss was all about. Far from home, the land and waters of Aram become to Naaman the locales of imagination. Many Victorians felt themselves to be intimately connected to the lands of Scripture, but they were largely unaware of the geographical features of this landscape (Van Haaften 1980: ix). Artists tended to depict the grand monuments, leaving the surrounding geography to the haze of imagination.

Victorians were overconfident in the evidentiary force of photography. Frith does not render the river itself, but frames a particular perspective, seemingly more invested in the photographic craft than the literal description of a landscape. What cannot be seen is Naaman’s impression of home. The appended text comments upon the image, but in a suggestive way. Even home becomes foreign when photographed. The water, blurred by time, is odd and unfamiliar. Naaman must choose the foreign. Elisha summons him to immerse himself in the chosen waters. To be healed he must do something new, and become something new: na’ar qaton, a little child.

The healing waters, the refreshed childlike skin of Naaman, all become suggestive of baptism for Christian readers. The Dutch tapestry depicts a very dour Naaman disrobed in the waters. His leprosy has already fled from his skin. He now belongs to this foreign land and its strange waters. Gehazi fails to see the change in Naaman. He says, ‘My master has let that Aramean Naaman off too lightly’ (2 Kings 5:20), insisting on treating Naaman as a stranger. The tapestry interprets baptism and Naaman’s healing in tandem. The sacrament incorporates the child into the Church, and the tapestry shows that the same has happened to Naaman. The child is baptized in the triune name; Naaman emerges from the waters uttering the name of God, saying that he will ‘no longer … sacrifice to any god except YHWH’ (2 Kings 5:17).

References

Boeckl, Christine M. 2011. Images of Leprosy: Disease, Religion and Politics in European Art (Kirksville: Truman State University Press)

Nelson, Richard. 1987. First and Second Kings (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press), pp. 176–83

Van Haaften, Julia. 1980. Egypt and the Holy Land in Historic Photographs: 77 Views by Francis Frith (New York: Dover Publications)

Commentaries by Stephen John Wright