Mark 16:19–20; Luke 24:50–53; Acts of the Apostles 1:1–11

The Ascension

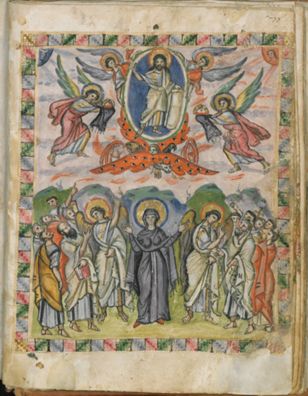

Unknown artist, Syria

Ascension, from the Rabbula (Rabula) Gospels, c.586, Tempera on parchment, 330 x 250 mm, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence; Cod. Plut. I. 56, fol. 13v, Su concessione del MiBACT, E' vietata ogni ulteriore riproduzione con qualsiasi mezzo / By permission of MiBACT, Any further reproduction by any means is prohibited

In No Way Parted

Commentary by Andrew Louth

This is really the icon of the Ascension, the earliest icon (though in a manuscript), that also established the iconography of the feast.

An icon does not depict an historical event, but a liturgical event: it is the liturgical meaning that the iconographer is trying to capture, not an historical scene.

The liturgical meaning of the Ascension is expressed in one of the verses for the kontakion (a verse sermon) of the feast, composed by Romanos the Melodist (c.500–after 555), just a few decades before the making of the sixth-century Rabbula Gospels:

When you had fulfilled your dispensation for us, and united things on earth with things in heaven, you were taken up in glory, Christ our God; in no way parted, but remaining inseparable, you cried to those who loved you: I am with you, and there is no one against you. (Lash 1994: 195)

The meaning of the Ascension for Christians is that everything Christ came to do has been fulfilled, that he is received into glory, without being separated from those who loved him, who have the assurance of his enduring presence with them. Christ departs, but his presence, his blessing (cf. Luke 24:51), remains.

In the icon, there is a clear separation between Christ ascending and the apostles who remain on earth, and yet that separation is not division—angels receive Christ; there are angels, too, with the Mother of God and the apostles.

In this icon, Mary, the Mother of God, is always depicted at the centre of the apostolic band (though Acts is not so explicit), and depicted in prayer, in the orans position, for it is prayer that bridges the distance between heaven and earth. Nor is the apostolic band ‘historical’, because the apostle Paul is clearly depicted, opposite Peter, for this is the apostolic Church in nuce, led by the leaders of the apostles, Peter and Paul.

References

Lash, Ephrem (Trans.). 1994. ‘On the Ascension, prelude 1,’ in Romanos the Melodist, On the Life of Christ: Kontakia (New York: HarperCollins)

Master of the Vyšší Brod Altar

Ascension of Christ, from the series 'Scenes from the Life of Christ', the Hohenfurth monastery, c.1350, Tempera on wood, 99 x 92.5 cm, Národní galerie Praha; NG O 6793, akg-images / André Held

Feet Last

Commentary by Andrew Louth

The general features of the icon tradition of the Ascension remain recognizable in this late medieval Western picture. It is a representation of Mary and the apostles; Jesus is in the process of vanishing into the cloud (cf. Acts 1:9). All we can see are his feet, sticking out. (In some other works, only the soles of his feet are visible.)

For late medieval pilgrims to Jerusalem, the mark of the soles of Christ’s feet on the summit of the Mount of Olives was a place of pilgrimage: it was, for example, this especially that St Ignatius of Loyola wanted to see on his pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1523 (Munitiz & Endean 1996: 35).

In contrast to the message of the Eastern icons, these Western accounts of the Ascension are rather about the absence of Christ, and, as Herbert Kessler and Robert Deshman have argued, about the event being ‘unwitnessed’ and therefore not fully representable (Kessler 2000: 132; Deshman 1997). Christ is no longer here on the earth. As the angels said to the disciples:

Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up into heaven? This Jesus who has been received up from you into heaven shall so come in like manner that you have seen him go into heaven. (Acts 1:11)

Compared with the icon in this exhibition, this picture is about the earth Jesus has left; heaven is not part of the picture. In such a this-worldly account historical verisimilitude holds sway: there are twelve apostles, with no trace of the ahistorical Paul of the icon.

We can also find this sense of the Ascension in Western liturgies—witness the collect in the Roman Missal: ut, qui hodierna die Unigenitum tuum, Redemptorem nostrum, ad caelos ascendisse credimus; ipsi quoque mente in caelestibus habitemus, which Cranmer rendered: ‘that like as we do believe thy only-Begotten Son our Lord Jesus Christ to have ascended into the heavens; so we may also in heart and mind thither ascend, and with him continually dwell…’ (Book of Common Prayer).

References

Deshman, Robert. 1997. ‘Another Look at the Disappearing Christ: Corporeal and Spiritual Vision in Early Medieval Images’, The Art Bulletin, 79.3, pp. 518–46

Kessler, Herbert. 2000. Spiritual Seeing: Picturing God's Invisibility in Medieval Art (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press)

Munitiz, Joseph and Philip Endean. 1996. Saint Ignatius of Loyola: Personal Writings (London: Penguin Books)

Donatello

The Ascension with Christ giving the Keys to St Peter, c.1428–30, Carved marble in very low relief, 40.9 x 114.1 cm; Weight: 60.5 kg, Victoria and Albert Museum, London; 7629-1861, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Left Behind

Commentary by Andrew Louth

Here we have an unusual and original depiction of the Ascension. It is clearly an Ascension, as we can tell from the figures present. Mary (with her back turned towards us) and the apostles are in prayer. Christ is raised up above the rest, apparently about to ascend. Angels, rather dimly, are in readiness to lift the throne on which he is sitting up to heaven which merges in some way with the clouds.

But the central focus is really on another ‘event’: the giving of the keys of the Kingdom to Peter, who stretches out his hand to receive them. This is presented as the Lord’s last action before departing for heaven, which had been promised after Peter’s confession of faith in Christ at Caesarea Philippi (Matthew 16:19).

As in many other Western treatments of this subject, we find here a sense that the Ascension is about Christ’s departure, and subsequent absence, from the world. But here Donatello gives it a further, and distinctly Catholic twist. Christ, now absent from the world, is present in it through his Church, led by St Peter, and his successors the popes, to whom he has bequeathed the keys of the Kingdom. The sense is that the historical institution of the Church, under the leadership of the Pope, is Christ’s presence in the world.

Donatello’s finely carved bas-relief was made in Florence barely a decade before an ecumenical Council was called in Ferrara, and then moved to Florence in 1439, in an attempt to reconcile the estranged Churches of the Eastern Byzantine Empire and the Western Papal Church. It may have been intended to sit below a niche housing a sculpture of Peter carved in the round. Together, these works would have focused the beholder’s attention on the historical claims of the Papal Church.

This sense of historical fact is enhanced by the treatment of the trees, less stylized and more naturalistic than in most earlier depictions, which emphasizes the earthly reality of the Mount of Olives, as do the walls and the towers of Jerusalem, which can be discerned in the distance.

Unknown artist, Syria :

Ascension, from the Rabbula (Rabula) Gospels, c.586 , Tempera on parchment

Master of the Vyšší Brod Altar :

Ascension of Christ, from the series 'Scenes from the Life of Christ', the Hohenfurth monastery, c.1350 , Tempera on wood

Donatello :

The Ascension with Christ giving the Keys to St Peter, c.1428–30 , Carved marble in very low relief

Let Heaven and Earth Combine

Comparative commentary by Andrew Louth

One problem in thinking about depictions of the Ascension is that, for most of the artists who have treated it (and still for most churchgoers), it is the liturgical celebration of the Ascension—forty days after Easter and ten days before Pentecost—that governs their/our sense of the Lord’s Ascension. It is imagined as an historical event that took place between the Resurrection and the Descent of the Holy Spirit.

But only Luke, in his Gospel and the book of Acts, thinks of the Ascension in such an historically defined way. Both Matthew, in the concluding verses of the Gospel (Matthew 28:16–20), and the last verses of the longer continuation of Mark (Mark 16:19–20), seem to suggest a much sooner end to Jesus’s Resurrection appearances, giving way to the preaching of the apostles. Meanwhile the Evangelist John speaks of Christ’s ‘ascending to the Father’ after the Resurrection in the context of Jesus’s encounter with Mary Magdalene in the garden on the morning of the Resurrection. Here, while there seems to be some kind of ‘not yet’ about the Ascension, it also seems just about to take place—and this on the day of the Resurrection itself. This entails a distance between the Magdalene and Christ, which Titian has perhaps most famously captured in his Noli Me Tangere.

As we have noticed, all three depictions in this exhibition confront the question of the historical. The fact that they respond to it in different ways highlights how the influence of more than one Gospel may be at work in them. Are these visual depictions of a specific event in time, or is something else going on?

What might be called a ‘Lukan’ approach is found in both the Western depictions, for both of them think of Christ’s departure and what comes next: the preaching of the apostles and the Church. The difference seems most marked if we compare the Rabbula Gospels’ illuminated page with Donatello’s bas-relief. For it is in the history of the institution of the Roman Church and its papal claims, resting on the donation of the keys, that Donatello sees the meaning of the Ascension; whereas the icon speaks of something more tangible and personal.

The manuscript icon could, moreover, be regarded as more ‘Johannine’ in that there is a marked sense of the collapsing of historical sequence: the apostles include St Paul, then historically still a persecutor of the Church. Furthermore, by including both heaven and earth in the picture, there is some sense that the division between heaven and earth is transcended in the Ascension. Christ is ‘in no way parted, but remaining inseparable’: an allusion to his human and divine natures, united but distinct.

Here the Christology of the Chalcedonian definition of faith informs the meaning of the Ascension. The union of heaven and earth is rooted in the union of human and divine in Christ. It is in the light of this reality, that any notion of separation or absence on Christ’s part dwindles into insignificance. It is affirmed at the heart of the liturgy, when the earthly Church, gathered before the altar, joins with the heavenly beings in singing the Sanctus.

Prayer is not at all absent from the Western depictions of the Ascension. Indeed, in addition to Mary, who is always depicted in prayer, some, at least, of the apostles seem to be praying, whereas in the Ascension from the Rabbula Gospels, their gestures seem rather of pointing to Christ, present enthroned in the heavens. But the notion of prayer seems different—something encouraged by the difference between the Eastern kontakion and the Western Collect for the Feast. Whereas the Eastern kontakion speaks of something dogmatically established (if we can put it like that), the Western collect speaks of a subjective personal ascent to be with Christ, whereby we may continually dwell with Christ, rather than the assurance of the kontakion that ‘I am with you, and there is no one against you’.

Commentaries by Andrew Louth