John 21:1–14

Stranger on the Shore

Lambert Sustris [attributed]; Circle of Jacopo Tintoretto

Christ at the Sea of Galilee, c.1570s, Oil on canvas, 117.1 x 169.2 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1952.5.27, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Coming in to Land

Commentary by Lauren Beversluis

Christ at the Sea of Galilee was most likely painted by the Dutch artist Lambert Sustris, working in the circle of Tintoretto in sixteenth-century Venice. The artist employs elongated proportions in his figures, cool and moody colours, and dramatic contrasts between light and dark.

An almost surrealistic landscape—playing somewhat freely with perspective and scale—gives the work a compositional tension. The luminous figure of Jesus stands large in the left foreground; his extended arm and raised finger direct our eyes to the disciples in the boat out on the water. They are minuscule relative to Jesus, suggesting a great distance between him and them. Yet the mountainous waves occupy the intervening space without diminishing in size, largely ignoring the rules of perspective. The effect is a kind of eeriness, even discomfort, and it forces the eye to work to situate the figures.

The cool and dark colours of the land-and-seascape evoke a hostile environment; they are counterbalanced by warm tones in the reassuring figure of Christ, who stands tall and beaming like a lighthouse upon the shore.

If we draw a straight line following Christ’s gaze through his raised finger towards the centre of the painting, we arrive at the top of the fishing net emerging from the water. Christ’s gesture thus probably represents his miraculous command to the seven disciples fishing in John 21:6, ‘Throw your net on the right side of the boat and you will find some [fish]’. At this, John is the first to recognize and announce the resurrected Christ, and Peter leaps into the sea to go to him, the latter here depicted with open arms and his full attention given to Jesus.

The depiction seems to hint that Peter may walk on water; he does not dive in, but takes a step—his right foot resting atop the waves of the stormy sea. There is little distinction between the sea and the land at Christ’s feet, creating the potential impression that Christ, too, walks upon the water. Sustris perhaps refers here to the earlier event described in Matthew 14:25–33, when Jesus invited Peter to walk to him on the waves. In that earlier episode, Peter ventured out, but soon began to sink, whereupon Jesus remarked, ‘Oh ye of little faith, why did you doubt?’. Now, with one foot in and one foot out of the boat, the viewer anticipates another test of Peter’s faith—one which Peter will ultimately pass (John 21).

References

n.d. Christ at the Sea of Galilee, NGA Online Editions, available at https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.41637.html [accessed 11 January 2024]

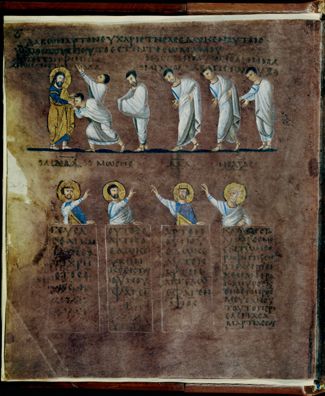

Unknown artist

The Communion of the Apostles: The Distribution of Bread, from the Rossano Gospels (Codex Purpureus Rossanensis), 6th century, Painted purple vellum, Diocesan Museum, Rossano Cathedral, Italy; Codex Purpureus Rossanensis; MS 042, fol. 3v, Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Known in the Breaking of the Bread

Commentary by Lauren Beversluis

The Rossano Codex is the oldest illustrated New Testament manuscript in existence, made of purple-dyed parchment and written with gold and silver ink. The fourteen pages of prefatory miniatures follow the liturgical order of the readings of Lent.

The miniature depicting the Communion of the Apostles is depicted on folio 3v, under the heading (in Greek): ‘Taking bread [and] giving thanks, he gave to them, saying, “This is my body”’. Six figures—men dressed in white tunics and mantles—process in a queue towards a haloed Jesus wearing the royal colours of gold and purple on the left. The first apostle bends over to kiss the right hand of Christ, whose left hand holds a small loaf of bread. The second figure raises his hands toward heaven, and the third’s hands are held out and reverentially covered, in anticipation of receiving the sacramental gifts. The remaining three figures appear to walk with their hands held open in front of them, in a gesture of prayer and reception.

Beneath this scene are four haloed male bust-length figures, labelled left to right as David, Moses, David, and Isaiah. Each figure raises a hand towards the procession above in a gesture indicating speech, and stands behind a large rectangular text box resembling a rostrum, which displays the content of their utterances. The first David on the left utters words from Psalm 33:9: ‘Taste and see that the Lord is good’. Next is Moses: ‘This is the bread which the Lord gave to you from heaven to eat’ (Exodus 16:15). Then David again: ‘Bread from heaven he gave to them; man ate the bread of angels’ (Psalm 77:24–5). And finally, Isaiah’s text reads: ‘And he sent to me one of the seraphim, and he had in his hand a coal of fire, and he said to me, “Son of Man, this will take away your sins”’ (Isaiah 6:6–7).

Each of these verses presents a typological and prophetic interpretation of the sacrament of the Eucharist occurring above, focusing particularly on the bread. These associations are reinforced by the facing folio, which shows a similar procession, with similar prophets and exegetical texts, and the reception of Holy Communion in the form of wine.

John 21, likewise, invites us—with the disciples—to find the Eucharist where we may not have expected it, as Jesus first takes and then shares bread on the beach.

References

Cavallo, Guglielmo, Jean Gribomont, and William C. Loerke. 1987. Codex Purpureus Rossanensis, Museo Dell’Arcivescovado, Rossano Calabro (Rome: Salerno Editrice)

Hixson, Elijah. 2016. ‘Forty Excerpts from the Greek Old Testament in Codex Rossanensis, a Sixth Century Gospels Manuscript’, The Journal of Theological Studies, 67.2: 507–41

Loerke, William C. 1961. ‘The Miniatures of the Trial in the Rossano Gospels’, The Art Bulletin, 43. 3:171–95

Weitzmann, Kurt (ed.). 1979. Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, 3rd–7th Century (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Duccio

Christ appearing to the Apostles on the Lake of Tiberias (from the Maestà), 1308–11, Tempera and gold on panel, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena; Scala / Art Resource, NY

Waving Not Drowning

Commentary by Lauren Beversluis

On 9 June 1311, the magnificent double-sided Maestà altarpiece painted by Duccio di Buoninsegna was reverently processed around the city of Siena before being installed in the cathedral. Its veneration and execution in the ‘Byzantine’ style —with relatively hieratic, flat figures and backgrounds of gold leaf—signal its debt to the icon tradition.

The front of the altarpiece displays the Madonna and Child, along with saints, angels, prophets, and scenes from Christ’s childhood. The reverse depicts forty-three scenes from the life of the Virgin and the life of Christ, including this image of the appearance of the resurrected Christ to the disciples on Lake Tiberias.

On the left side of the panel, Christ stands on the shore, the folds of his clothes highlighted with gold—the artist using a technique known as chrysography. He gestures towards the disciples in the fishing boat on the right, the closest being Peter, who steps towards him on the water, holding out his hands. The bottom of the boat and the fish are depicted as in the water, beneath a layer of translucent waves. In contrast, Peter is shown to stand on the water’s surface; his feet are untouched by the waves. In an unnatural distortion of space, his feet are placed to appear nearer to us than the boat, even though his upper left leg is behind the boat.

In a manner also typical of icons, there is a flattening and collapsing effect, which highlights the spiritual and emotional closeness of the figures. This occurs despite the figures’ expressionlessness, which conveys an overall impression of dignity and poise.

Peter’s leap into the sea (John 21:7) is rendered here as his walking on water, as in Matthew 14:25–33. By invoking this pre-resurrection episode in the context of John 21:1–8, Duccio’s work emphasizes the new strength of Peter’s faith—a faith which is restored after his denials and repentance during Christ’s Passion, and which foreshadows his repeated affirmations of love in John 21:15–19. In contrast to the other disciples, Peter is shown to have fully left the boat (with a total disregard for the fishing task at hand). He faces Christ with open arms, and at eye level; they might be in close conversation. In this way Duccio preserves the impulsive apostle’s dignity, and underscores his primacy over the other disciples.

References

Weber, Andrea. 1998. Duccio di Bunoninsegna: About 1255–1319, Masters of Italian Art, 6 (Köln: Könemann)

Lambert Sustris [attributed]; Circle of Jacopo Tintoretto :

Christ at the Sea of Galilee, c.1570s , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist :

The Communion of the Apostles: The Distribution of Bread, from the Rossano Gospels (Codex Purpureus Rossanensis), 6th century , Painted purple vellum

Duccio :

Christ appearing to the Apostles on the Lake of Tiberias (from the Maestà), 1308–11 , Tempera and gold on panel

Feed on Him by Faith

Comparative commentary by Lauren Beversluis

All three of our artworks depict an ethereal and majestic Christ standing on the left side of the composition and gesturing to his disciples, who adopt attitudes of reception, whether to his word or to his miraculous, sacramental food.

In Lambert Sustris’s painting, it is Peter alone who gazes at Christ and ventures to come to him, even from a distance. Duccio’s composition similarly features Peter coming first to Christ, though all seven are near to him and most gaze at him. In the Rossano illumination, the six disciples are unidentifiable, and all come to Christ in postures of thanksgiving and reception.

Unlike the Sustris and the Duccio works, the Rossano illumination does not explicitly depict the events of John 21, nor any single scriptural episode. Instead, it depicts the Communion of the Apostles, an archetypal sacrament reflected in the eucharistic liturgy at every mass. Yet although the Rossano miniature is non-narrative in character, it has any number of scriptural resonances and exegeses, as can be seen in the prophetic speech boxes below it. Arguably, John 21:12–13 also fits among these verses:

Jesus said to them, ‘Come and have breakfast.’ None of the disciples dared ask him, ‘Who are you?’ They knew it was the Lord. Jesus came, took the bread and gave it to them, and did the same with the fish [my emphasis].

This passage is reminiscent of Luke 22:16, which is recited by the celebrant during the consecration of the Eucharist: ‘And he took bread, gave thanks and broke it, and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body given for you; do this in remembrance of me”’. In addition to the Last Supper, the Gospel episodes of the miracles of the loaves and fishes are germane, and can be interpreted in light of the Communion of the Apostles.

When Christ enables the miraculous catch of fish in John 21 (echoing the earlier miraculous catch of fish and calling of Peter, James, and John in Luke 5:1–11) it is not simply food that he provides, but a communication of his very self. This is why Peter abandons the nets and the boat to go and receive (and be received by) Jesus directly. An attitude of receptivity towards Christ characterizes the disciples, especially Peter, in John 21 and in the works in this exhibition.

Such attitudes ought also to characterize communicants who partake of the eucharistic elements, as the Rossano miniature makes plain. St Augustine also affirms this in his commentary on John 21:12–14:

The fish roasted is Christ having suffered; He Himself also is the bread that cometh down from heaven. With Him is incorporated the Church, in order to the participation in everlasting blessedness. For this reason is it said, ‘Bring of the fish which ye have now caught,’ that all of us who cherish this hope may know that we ourselves, through [the seven disciples, which here symbolize] our universal community … may partake in this great sacrament, and are associated in the same blessedness. (Augustine, ‘Tractate 123’, John)

In addition to the theme of eucharistic reception, the issue of faith in Jesus is also foregrounded in our works. The Sustris painting seems to follow a visual tradition—as exhibited in the earlier panel from the Maestà—of depicting Peter as walking, or almost walking on water, following Matthew 14:25–33. If Peter now no longer sinks, as he did in this earlier episode, then Peter must no longer doubt; he is ultimately resolute in his faith in Jesus.

Peter’s faith is a central topic of John 21. After the disciples reach the shore and eat breakfast with Jesus, Jesus turns to Peter and asks thrice, ‘Simon, son of Jonah, do you love me?’ Thrice Peter responds, ‘Yes Lord, you know that I love you,’ reversing his three denials of Jesus a few days prior (John 18:17, 25, 27). Jesus replies, ‘Feed my sheep/lambs’, underscoring that Peter’s faith must now be demonstrated through ministry to his flock, despite the prospect of martyrdom (John 21:18–19). The Sustris and Duccio paintings display Peter’s apparent readiness to do so as he leaves the safety of the boat to walk atop the stormy sea. While in the Gospel account John is the first to recognize the resurrected Jesus, it is Peter who first acts upon his faith by jumping into the water to come to him.

The unifying concept underlying these three works, therefore, is the disciples’ faith in and reception of Christ—the Word that he is and pronounces, and the Living Bread (and Fish) that he is and provides to his Church.

References

Augustine. ‘Tractate 123’. Trans. by John Gibb and James Innes. 1888. St Augustin: Holilies on the Gospel and First Epistle of John, Soliloquies, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers Series 1, vol. 7, ed. by Philip Schaff (New York: Christian Literature Publishing)

Commentaries by Lauren Beversluis