2 Samuel 11:1–4

Bathsheba Bathing

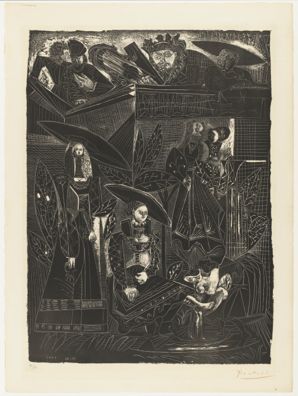

Pablo Picasso

David and Bathsheba, after Lucas Cranach, 1949, Lithograph, 760 x 562 mm (sheet), The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Curt Valentin Bequest, 363.1955, ©️ 2023 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Image: ©️ The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Exposure, Over and Under

Commentary by Sara M. Koenig

It is possible that Bathsheba was not bathing naked. While images of a nude Bathsheba are far more widespread than those of her bathing clothed (Vadillo 2008: 40), there are several illustrations of her fully dressed, and only bathing her feet. The German Renaissance painter Lucas Cranach the Elder, for example, painted such an image of Bathsheba in 1526 (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), and that image inspired this lithograph by Pablo Picasso. Working on a zinc plate, Picasso scraped out thirteen states—the different forms a plate takes while being produced for printmaking—between 1947 and 1949, printing various impressions as he proceeded.

Picasso adopted Cranach’s composition with King David and his attendants on a balcony watching Bathsheba get her feet washed by an assistant in a pool below the palace. In Picasso’s version, Bathsheba and the other women wear the sixteenth-century attire of Cranach’s time, including hats with distinctive slanted brims.

But Picasso notably altered Cranach’s composition in two significant places. First, while Cranach’s painting merely hints at the servant’s cleavage, Picasso depicted the servant’s breasts falling out of her dress. The servant’s exposure contrasts with Bathsheba’s modesty: as is typical in these images of Bathsheba bathing clothed, Picasso has shown only her foot and ankle as bare. Second, Picasso represented David with a disproportionately large, almost monstrous head. While Cranach’s David looks down intently at the bath, Picasso’s leers menacingly over the wall.

The threat of David’s power, of David’s position, of David’s gaze, is all the more vividly expressed because of its contrast with Bathsheba’s innocent and decorous bath.

References

Walker Vadillo, Monica Ann. 2008. Bathsheba in Late Medieval French Manuscript Illumination: Innocent Object of Desire or Agent of Sin? (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen)

Jean-Léon Gérôme

Bethsabée (Bathsheba), 1889, Oil on canvas, 60.5 cm × 100 cm, Private Collection; Historic Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Limited Availability

Commentary by Sara M. Koenig

Jean-Léon Gérôme, a French painter already known for his other images of bathing women—such as La Grande piscine à Brusa (1885)—made Bathsheba the subject of this 1899 painting.

The Bible does not specify the type of Bathsheba’s bath: it could, for example, have been a ritual bath given the mention of purification in 2 Samuel 11:2, though several English translations simply say that Bathsheba was ‘washing herself’.

Gérôme shows it as a more quotidian bath, though located in a rather spectacular setting on a roof terrace in the open air. A female servant kneels in front of Bathsheba, assisting with her bath. (While no servant is mentioned in the biblical story, the artistic interpretations of Bathsheba’s bath often include one or two assistants.) Bathsheba stands washing herself on a richly hued green and red rug, colours which mirror the plants and flowers to her left. Bathsheba’s own naked body is pale white and rosy pink, complementing the shades of pink and gold in the sky, as well as the colours on the light in the buildings in the distance. This scene seems to be set at sunset (as 2 Samuel 11:2 indicates, the bath took place ‘late one afternoon’).

This is a sensual painting without necessarily being seductive: Bathsheba is enjoying the water and fresh air on her body after the heat of the day. She is exposing herself to the city, but those buildings are too far away from her for anyone to see her clearly. Only her assistant—and David, who is almost an afterthought in the top left of the composition—could see her frontal nudity.

While David’s body language suggests some surprise at seeing Bathsheba, at this moment she is not aware that he is watching her. Because this happens at ‘the time when the kings go out to war’ (2 Samuel 11:1), Bathsheba would not expect David the king to be present in Jerusalem. She takes pleasure in her own body and the sensation of her bath for its own sake.

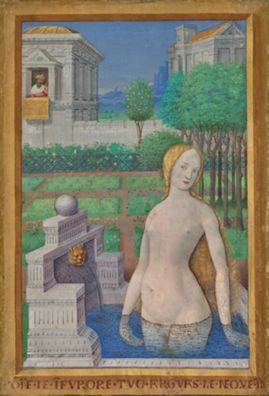

Jean Bourdichon

Bathsheba Bathing, 1498–99, Tempera and gold on vellum, 243 x 170 mm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Ms. 79, recto, 2003.105.recto, Digital image courtesy of Getty’s Open Content Program

A Compromising Position

Commentary by Sara M. Koenig

One of the most overtly seductive images of Bathsheba is found in the Book of Hours of Louis XII (c.1498–1499), in which court painter Jean Bourdichon depicted her in a deliberately provocative manner. She is explicitly, even graphically naked: though she is immersed in water to her hips, her genitalia are visible under the water (Kren 2005: 44). Bourdichon may have included some bawdy humour by painting a cat as the spout of the fountain in which Bathsheba is bathing, because chatte meant ‘prostitute’ in the French slang of that time (ibid: 57–58).

Bathsheba frequently appeared in Books of Hours from the medieval era. These private prayer books, which allowed laypeople to follow along with the church’s canonical hours of prayer, included the seven penitential Psalms as a standard part of their liturgy. The superscription to Psalm 51 introduces it as ‘a psalm of David, when Nathan the prophet came to him after he went to Bathsheba’. Illustrations of Psalm 51 in Books of Hours often included images of Bathsheba bathing, suggesting that was the catalyst which necessitated David’s penance.

In Bourdichon’s version, David is visible in the upper left corner of the illumination, watching Bathsheba from the window of the palace beyond the garden wall. The direction of Bathsheba’s eyes, turned to the right while she cocks her head to the left, suggests she is aware of his gaze. But David would not be able to see much from his vantage point; only her back would be visible, with her hair covering even that.

Louis XII, who was infamous for his infidelity and sexual appetite, likely enjoyed and was titillated by this view of Bathsheba (Kren 2005: 57). Now we—the contemporary viewers—are the voyeurs of this Bathsheba, who is presenting herself openly, even brazenly, to us. Such a view depicts her bath as a seduction and her as a seductress.

References

Kren, Thomas. 2005. ‘Looking at Louis XII’s Bathsheba’, in A Masterpiece Constructed: The Hours of Louis XII, ed. by Thomas Kren and Mark Evans (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum)

Pablo Picasso :

David and Bathsheba, after Lucas Cranach, 1949 , Lithograph

Jean-Léon Gérôme :

Bethsabée (Bathsheba), 1889 , Oil on canvas

Jean Bourdichon :

Bathsheba Bathing, 1498–99 , Tempera and gold on vellum

Finding an Angle

Comparative commentary by Sara M. Koenig

While Bathsheba does many different things in the Bible—gets pregnant, mourns her husband Uriah, needs comfort after her first child dies, gives birth to and names Solomon, helps Solomon succeed his father on the throne, and becomes the queen mother—artworks representing her story all focus on her bath.

This emphasis began in Western art during the medieval era, when manuscript illuminations of Bathsheba bathing accompanied the text of Psalm 51, one of the seven penitential psalms. Bathsheba’s textual connection with Psalm 51 is thin, as she is only mentioned in the superscription, but the iconographic expressions of her bath in this time period are robust. Eventually, in ways analogous to how David became visually identified with his harp, Bathsheba became visually identified with her bath. It became part of her iconography.

Hebrew narrative is known for being terse, with few details about appearances, feelings, or motives. But the story in 2 Samuel 11 is, according to biblical scholar Meir Sternberg, ‘frugal to excess even relative to the biblical norm’ (Steinberg 1987: 191). The dearth of information allows for a variety of interpretations of Bathsheba’s bath, as 2 Samuel 11:2 merely states that David ‘saw a woman bathing’. Was this a practical, necessary bath? Was it a ritual purification? Was it a sponge bath, or was she fully immersed? Was she naked or partially clothed? Did she know she was being watched?

Various answers to these questions will lead to various interpretations of Bathsheba’s character. Understood one way, Bathsheba is an exhibitionist, displaying her nakedness by publicly bathing where she could be seen. Understood another way, David is spying on a woman unaware that she is being watched while she bathes; he is a ‘Peeping Tom’ like the wicked elders in the deuterocanonical story of Susanna, or worse. The art generated by this story literally helps us envision different options, and the three artworks in this exhibition represent a variety of possibilities for understanding Bathsheba’s bath and the events that follow in her story.

Each artwork has located Bathsheba’s bath in a different place: Jean-Léon Gérôme has her bathing on a roof terrace; Jean Bourdichon placed her bath in a private garden; and Picasso put her in a public pool. This array of locations can be traced to the ambiguity in the Hebrew preposition in 2 Samuel 11:2 describing David’s initial viewing of the bath, as it is a compound preposition made up of two words, ‘from’ and ‘upon’ (מֵעַל, mēʿal). Many English translations only translate the first, emphasizing that David saw Bathsheba bathing from his location on the roof. But the second word in the compound allows for the tradition of Bathsheba bathing ‘upon’, or ‘on the roof’.

The three artworks also differ in how much of Bathsheba’s body can be seen, and by whom. Pablo Picasso, following Cranach, depicts Bathsheba fully clothed with only her foot and ankle exposed. Gérôme has Bathsheba completely naked, and David can see her full-frontal nudity. Viewers of Gérôme’s painting, though, only see her from behind, so this image is perhaps less explicitly erotic than Bourdichon’s version, in which Bathsheba is exposing herself completely to the viewers. In Bourdichon’s illumination, David cannot see Bathsheba; we can. We might view Gérôme’s painting as a depiction of a woman enjoying the sensory pleasures of her bath; Bourdichon depicts a seductress who smiles at her viewers knowingly and enticingly.

The terse nature of the story continues in the events narrated after the bath: Bathsheba ‘came to him, and he lay with her’ (2 Samuel 11:4). Was her arrival indicative of any desire on her part, or was it impossible to resist a summons from the king? Was the sexual encounter consensual, or forced? For centuries, the sexual act between David and Bathsheba was referred to as ‘adultery’. It is only in the past few decades that people have suggested the language of ‘rape’; this language became more prevalent after women began sharing stories of sexual assault and trauma when #metoo went viral in 2017 (Scholz 2010: 100; Lamb 2015: 134; Brooks 2015: 232). Based on Bourdichon’s presentation, it would not be hard to imagine Bathsheba eagerly coming to David. But Picasso’s David, painted with a malevolent expression on his face, hints at something darker and more violent than simple sexual desire. Consensual sex, a woman’s sexual initiative and pleasure, sexual abuse, and assault: all these interpretations are possible for the story surrounding Bathsheba’s bath, and all of them have real-life implications in our world today.

References

Brooks, Geraldine. 2015. The Secret Chord (New York: Viking)

Lamb, David T. 2015. Prostitutes and Polygamists: A Look at Love, Old Testament Style (Grand Rapids: Zondervan)

Sternberg, Meir. 1987. The Poetics of Biblical Narrative (Bloomington: Indiana University Press)

Scholz, Suzanna. 2010. Sacred Witness: Rape in the Hebrew Bible (Minneapolis: Fortress Press)

Commentaries by Sara M. Koenig