2 Samuel 6; 1 Chronicles 13 & 15:1–16:6

David Dances before the Ark

Works of art by Limbourg Brothers, Unknown English artist and Unknown French artist [Paris]

Unknown English artist

David Bringing the Ark of the Covenant to Jerusalem, from Illustrated Vita Christi, c.1480–90, Illumation of tempera colours and gold leaf on parchment, 119 x 170 mm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Ms. 101 (2008.3), fol. 14r, Image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program

Spreading the Joy

Commentary by Beth Williamson

This page shows two closely related scenes. In the upper field, King David gathers the chosen men of Israel, and prepares for the return of the Ark of the Covenant to Jerusalem. The partly obscured heads of the figures in the rear are an attempt to suggest a crowd, to represent the thirty thousand men whom David supposedly brought together for this purpose (2 Samuel 6:1).

In the lower register, the Ark is carried to Jerusalem. It takes the form of a golden ‘aedicule’ reliquary—a structure in the shape of a small building. Such objects would have been familiar to fifteenth-century viewers as containers for something extremely holy. Here it is carried on poles upon the Levites’ shoulders (1 Chronicles 15:15).

Jerusalem is represented by the stone city gate within which David stands. He receives the Ark, rather than leading the procession. This may be a departure from the letter of the biblical text, but perhaps it allows a christological parallel to be played out. The Ark was understood in certain medieval commentaries (e.g. Pseudo-Ambrose [Maximus of Turin], Sermon 42.5) as representative of the Virgin Mary. The Ark contained the tables of the Law (which sealed the first covenant) while the Virgin contained the body of Christ (which sealed the second). In receiving the Ark into Jerusalem this David seems to cement the connection of Christ, born of Mary, with his own kingly line of succession.

There is a further Marian resonance in this scene of welcoming encounter: an echo of the Visitation. When Elizabeth sees Mary she asks, ‘And why has this happened to me, that the mother of my Lord comes to me?’ (Luke 1:43). The verse in Luke is itself an echo of 2 Samuel 6:9, when David asks, ‘How can the Ark of the Lord come into my care?’.

The Ark is accompanied by two musicians, one playing a harp. The harp is positioned near to David, appearing to be closely associated with him even though he does not hold it. It is almost as though the musician has taken temporary charge of David’s familiar instrument and now plays it as his proxy in service of the noisy celebrations attending the Ark’s arrival. On this reading, the harp, like David’s jubilation, is shareable—and viewers of this illumination are being invited to share that jubilation too.

Limbourg Brothers

The Ark being carried into the Temple, from Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, Fifteenth century, Illumniation on vellum, Le musée Condé, Chantilly, France; MS 65, fol. 29, Photo: René-Gabriel Ojéda © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

‘Lift up your Heads, O Gates!’

Commentary by Beth Williamson

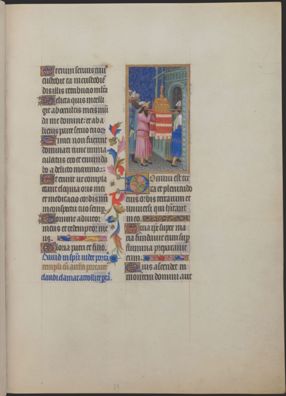

This illumination appears within one of the best-known manuscripts of the later Middle Ages. It was made for the Duc de Berry, who was one of the most illustrious collectors and patrons of art of his day. The miniature depicts the Ark of the Covenant being carried in procession into the Temple at Jerusalem, and accompanies one of the psalms that were interspersed throughout Books of Hours.

Here, the Temple is shown as a Gothic church, with a rose window, carved stonework portal, and flying buttresses. The Ark is represented as a gilded metalwork reliquary, itself in the shape of a miniature Gothic building.

The psalm in question is Psalm 24 (23 in the medieval numbering of the Psalms), verse 7 of which declares ‘Lift up your heads, O gates! And be lifted up, O ancient doors! That the King of glory may come in’. The titulus (the text in blue and gold that explains what is about to be seen in the book) reads: ‘David in spirit sees the gates of the Temple closed when the ark is being carried there and cries out “O gates lift up your heads”’.

The text ‘Lift up your heads, O gates!’ was used liturgically for the dedication of a church, and for the entry of the procession into the church on Palm Sunday. This links the psalm included at this point in the Book of Hours to the narratives concerning David of 2 Samuel 6, and Chronicles 13, and Chronicles 15–16 , as well as forward to the Gospel accounts of Jesus’s triumphal entry (Matthew 21:1–11; Mark 11:1–11; Luke 19:28–44; John 12:12–19). It ensures that the reader of this Book of Hours would have understood the Christian liturgy as linked to, and fulfilling, these Old Testament texts.

Unknown French artist [Paris]

David's Greatest Triumph, The Ark Enshrined in Jerusalem, David Blesses Israel, from The Crusader Bible (The Morgan Picture Bible), c.1244–54, Illumination on vellum, 390 x 300 mm, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; Purchased by J.P. Morgan (1867–1943) in 1916, MS M.638, fol. 39v, Photo: The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

A Merry-Making Monarch

Commentary by Beth Williamson

The Morgan Bible’s concentration on kingly stories—especially of King David—seems to be designed to appeal to a royal patron. The Bible was probably created in Paris for Louis IX of France around the years 1244–54. This illumination asks us to consider what royal dignity and royal duty demand.

In the upper register, David, crowned and wearing an ermine-lined cloak, leads the procession carrying the Ark of the Covenant into Jerusalem. This was a moment of huge significance in the biblical story, because, with the Ark, God’s glory came to Jerusalem. It was an occasion for celebration. The king leaps and dances.

The artist has assumed that David, as he danced, was one of the many who were playing musical instruments (2 Samuel 6:5). Presumably David is given a harp here (the texts do not mention the instrument) because he is commonly shown with his harp in other depictions, such as at the start of Psalm 1, and because he had played the harp for Saul (1 Samuel 16:14–23).

The Ark was God’s throne; it was holy. Once it had arrived in Jerusalem, it established that city as the centre of Israel’s worship, as well as the political capital of David’s kingdom. The altar and the candles and the sacrifice of animals in the lower register reflect the worship that David later commanded (2 Samuel 6:17–18).

This grand entry notwithstanding, David’s legitimacy was challenged. We can see this at the very top right of the illumination in the figure of Michal, David’s wife (the daughter of his predecessor, Saul) who leans out of a window and appears to reprimand him. 2 Samuel 6:16–20 tells of Michal despising David for his dancing, because it did not seem to her to fit with the royal dignity. David reproves her (vv.20–21) and sets out his understanding of kingly rule under God.

Medieval commentators, including Gregory the Great, noted that by dancing before the Lord David overcame himself, and made himself noble through humility (Gregory Moralia in Job, 27.46). His dancing is both exultation, and an act of personal abasement. David is thus shown to be noble in a truer sense—an appropriate message for a royal book.

Unknown English artist :

David Bringing the Ark of the Covenant to Jerusalem, from Illustrated Vita Christi, c.1480–90 , Illumation of tempera colours and gold leaf on parchment

Limbourg Brothers :

The Ark being carried into the Temple, from Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, Fifteenth century , Illumniation on vellum

Unknown French artist [Paris] :

David's Greatest Triumph, The Ark Enshrined in Jerusalem, David Blesses Israel, from The Crusader Bible (The Morgan Picture Bible), c.1244–54 , Illumination on vellum

A Triumphal Entry

Comparative commentary by Beth Williamson

In 2 Samuel 6: 1–15 and its parallels in 1 Chronicles, King David brings the Ark of the Covenant triumphantly into his city of Jerusalem.

This fundamentally important artefact had been built by the Israelites (according to the detailed instructions in Exodus 25) to hold the tablets of the law given to Moses by the Lord on Mount Sinai. These instructions included the pledge that God would dwell among his people, speaking to them ‘from between the two cherubim that are upon the ark of the testimony’ (Exodus 25:22).

Thus, the Ark was the locus, and the sign, of God’s presence. The Israelites carried the Ark with them during their wanderings in the desert, and whenever they camped it was placed in the sacred tent called the Tabernacle.

Later, after their settlement of the Promised Land, 1 Samuel 4 tells how the Israelites’ decision to bring the Ark to the battlefield resulted in its capture by the Philistines. Later still, it would be returned, but it was only when David was anointed king of Israel that it would come to its resting place in Jerusalem.

This was significant in several ways: it established the throne of David and his true kingship; it also made Jerusalem not just the political centre of Israel under David, but also the Holy City of God, the place in which the Israelites encountered the divine presence.

Thomas Aquinas, following patristic precedent, understood the tablets of the Law within the Ark as a foreshadowing of Jesus Christ, the Word incarnate, God present on earth (Summa Theologica I-II. 102.4). This explains why the Ark’s entry into Jerusalem is depicted as it is in the Très Riches Heures. The illumination does not illustrate the psalm so much as place its words within a network of typological connections. The reference to ‘the King of Glory entering in’ (Psalm 24:7) is made to recall the entry of the Ark—as the throne of God’s presence—to Jerusalem. But the Ark in turn points to Christ’s later triumphal entry into Jerusalem, which the Christian Church celebrates on Palm Sunday.

The account of the bringing of the Ark to Jerusalem is more extended in 1 Chronicles than in 2 Samuel. 1 Chronicles 13 and 15 offer an elaborate treatment of the arrangements that David makes for the Ark’s transportation. And central to these arrangements is his command that the Ark should be carried into Jerusalem to the accompaniment of exuberant music (1 Chronicles 15:16–25). In 2 Samuel 6:5 we hear about the ‘songs and lyres and harps and tambourines and castanets and cymbals’. And in 1 Chronicles 13:8, we hear that ‘David and all Israel were making merry before God with all their might, with song and lyres and harps and tambourines and cymbals and trumpets’.

David was the harpist who could calm Saul’s restless soul when he played (1 Samuel 16:14–23) and is celebrated as the composer of the Psalms, so the centrality of music in this episode should perhaps be no surprise. Joyous noise was also a demonstration of the momentousness of the occasion.

In the same way, music accompanies important moments in the liturgy of the Christian Church. It is notable that Palm Sunday was one of the feasts treated with the most elaborate ceremonial, processions, and music in the whole of the Christian liturgy.

Each of the images shown here presents the ceremonial and the procession accompanying the Ark’s entry into Jerusalem as crucially important. They all also pay visual homage to music. In the two illuminations which depict the Ark’s entry in order to illustrate the Davidic narrative directly (from the Morgan Bible and the Vita Christi), the music-making is explicitly represented within the image. And although there is no direct representation of music in the Très Riches Heures, it is implied in the link made with the psalm used for Palm Sunday.

David’s story (like that remembered on Palm Sunday) reminds the viewers of these images that the right model of kingship and authority is one that is humble. It also reminds viewers that, in the presence of God, they should be jubilant.

![David's Greatest Triumph, The Ark Enshrined in Jerusalem, David Blesses Israel, from The Crusader Bible (The Morgan Picture Bible) by Unknown French artist [Paris]](https://images-live.thevcs.org/iiif/2/AW0557_Davids+Greatest+Triumph_MLM-edited.ptif/full/!400,396/0/default.jpg)

Commentaries by Beth Williamson