Matthew 4:23–25; 12:15–21; Mark 3:7–12; Luke 6:17–19

Healing the Multitude

Benjamin West

Christ Healing the Sick in the Temple, 1817, Oil on canvas, 3.04 x 4.5 m, University of Pennsylvania Hospital; Courtesy Pennsylvania Hospital Historic Collections, Philadelphia

Stepping In

Commentary by Rossitza B. Schroeder

Painted for the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia, this work invites a comparison between the doctors working there and Christ in his ministry of healing. The text that inspired it is Matthew 21:14–15 which describes Jesus restoring ‘the blind and the lame’ in the Temple. The event occurs immediately after his Entry into Jerusalem which marks the beginning of the Passion narrative. Before these healings, Christ had chased away the moneychangers—the ‘cleansing’ of the space paralleled with the ‘cleansing’ of the diseases plaguing the people gathered around him.

Although slightly off-centre, the figure of Jesus dominates the composition. His arms are opened wide, toward us as much as toward the brightly lit paralytic, in a gesture that speaks of welcome and acceptance, and that invites participation in the miracle. Indeed, the empty space immediately to Christ’s left, and a little in front of him, allows the viewer imaginatively to ‘step in’, momentarily becoming one of the people seeking his cure and—by extension—absolution and salvation.

The paralytic is brought before Christ by two muscular figures, who might be servants. The sick man is wrapped in luminous white fabric. Iconographically, he seems less a typical paralytic than a Lazarus-like figure who had just been resurrected. The healing that is about to occur thus seems more than a restoration of physical health; it is also a gift of new life.

Noteworthy is the group to Christ’s left, clustered around a demoniac boy. His body is greyish blue, his facial features distorted by an uncontrollable spasm, and his limbs flailing; he is being restrained by an older male figure, his father perhaps. In an earlier version of the painting this subject was omitted. In a letter dated to 5 September 1815, West noted how important it was to include a demoniac, as he epitomized most of the maladies healed by Christ.

‘Let the children come to me’ (Matthew 19:13). An important feature of the painting is its emphasis on parents and children. A young mother at left, cradling her sick child, has fallen to her knees gently supplicating with her left hand. Behind her, an older man with a balding head supports a young blind girl while directing his hopeful gaze toward Christ. Immediately to Jesus’s left, a blind beggar is accompanied by a young boy. In the background, we see a mother holding a young child evoking some of Raphael’s Madonnas.

References

Von Erffa, Helmut and Allen Staley. 1986. The Paintings of Benjamin West (New Have: Yale University Press), pp. 346–50

Robinson, John. 1818. A Description of, and Critical Remarks on the Picture of Christ Healing the Sick in the Temple; Painted by Benjamin West Esq. and Presented by Him to the Pennsylvania Hospital (Philadelphia: S. W. Conrad)

West, Benjamin. 1805. ‘Letter to the Hospital Discussing His Gift and Exhibition of His Painting’, available at: https://www.uphs.upenn.edu/paharc/history-day/painting/west-letter-to-hospital.jpg [accessed 15 January 2024]

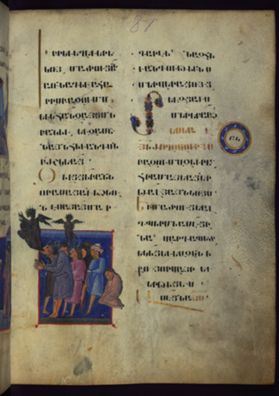

T'oros Ṙoslin

The Sick and the Possessed, from the T'oros Roslin Gospels, 1262, Illuminated manuscript, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore; W.539, fol. 40r, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore / CC0 1.0

The Power of the Word

Commentary by Rossitza B. Schroeder

This manuscript illumination accompanies Matthew 8:16–18, which describes Jesus’s healing of a multitude of people. An inscription in Armenian identifies that these are the ‘sick and the possessed’ mentioned in the Gospel passage.

Curiously, the painter T’oros Roslin, chose not to visualize Christ’s engagement with the crowds (v.18) who brought the infirm to him. Instead, only the sick people are represented; most of them demoniacs as indicated also in Matthew’s text. From the mouths of three males issue dark, nude, winged figures—devils of some sort—which was a standard way to represent exorcism. All appear to be poor with their simple short tunics and bare feet. One of the people at the back of the crowd, a paralytic, is leaning on a staff; he also wears a turban which is perhaps meant to indicate a different ethnicity.

On the margins of the illumination and spilling beyond its frame is a kneeling figure with his head bowed and with hands folded in his lap. This is a posture associated more with contemplation and penance than with illness; physical affliction and its cure is thus given a spiritual dimension. A healthy body indicates also a healthy soul, a physical cure is paralleled with spiritual absolution.

The background is minimal. There are no architectural or even landscape elements to suggest the specific location of the figures. Interestingly, the figures all face left in the direction of the miniature across the manuscript’s gutter on folio 39v where Peter’s mother-in-law, healed by Christ (as described in Matthew 8:15), is ministering to the disciples.

What distinguishes this illumination is the conspicuous omission of Christ. How then are the various people being cured?

Matthew’s accompanying text provides an answer: he specifically indicates that the healing was effected by Christ’s words, not hands, or contact with substances and clothing (see the Healing of the Man Born Blind in John 9:1–12 or the Healing of the Woman with an Issue of Blood in Luke 8:43–48).

These holy words abound on the pages of the manuscript; the Gospel text itself, beautifully written and occasionally lavishly adorned, is what expels the demons from the sick people depicted there. The words written in the manuscript equate with the salvific healing words spoken by Christ, thus turning the book into the ultimate healing agent.

References

Mahoney, Lisa. 2010–11. ‘T’oros Roslin and the Representation of Pagan Threat’, The Journal of the Walters Art Museum, 68–69: 67–76

Unknown artist

The Healing of the Multitude, 1320s, Mosaic, Kariye Camii, Istanbul; EVREN KALINBACAK / Alamy Stock Photo

Quotations and Transformations

Commentary by Rossitza B. Schroeder

This mosaic was created is in what was originally a chapel intended for commemorations of the dead and for penance. It belongs to a long cycle of depictions of curative miracles within the church and is one of the very few known monumental representations of the healing of the multitude in Byzantine art. It has been proposed that the biblical source for the image is the healing described in Matthew 15:29–31. The Greek inscription—not a direct quotation from any Gospel—simply states that Christ is ‘healing those afflicted with various diseases’.

The event unfolds outside a city (hinted at by the buildings in the background). Christ, followed by three disciples, approaches from the left and leans gently in the direction of the sick people who take up the right half of the composition. Four men and four women advance from the right. A lush, fruitful tree prominently separates the two groups.

A supine blind paralytic is represented at the base of the tree, invoking images of the Tree of Jesse. There is no doubt that this unusual iconographic ‘quotation’ was deliberate, yet its intention remains unclear. It is possible that this figure meant to redirect the viewer toward the dome which crowns the chapel, where Christ is seen surrounded by His human ancestors.

At the end of the line is a woman leaning on a stick, severely bent over. This iconography—commonly employed for the woman with a curved back in Luke 13:10–17—is sometimes also used for the adulterous woman in John 8:1–11. This visual overlap shows that, in the imagination of the Byzantines, physical sickness and sinfulness were aligned.

Behind this man is a seated figure with an enlarged growth protruding from his right thigh. This is unique among the various illnesses depicted in Byzantine art and it might be reflective of a specific condition treated at a hospital associated with the Chora. One of the women incorporated in the composition eagerly offers her child in a gesture that resembles that of the Virgin Mary in the images of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple.

In multiple ways, the artist was clearly relying on well-known iconographic tropes in order to imbue his images with new meanings. In this case, the eager mother is transformed into the ultimate model of womanhood, the Theotokos (or ‘God-bearer’), and the sick child into the young Jesus.

References

Rossi, Maria Alessia. 2019. ‘Reconsidering the Early Palaiologan Period: Anti-Latin Propaganda, Miracle Accounts, and Monumental Art’, in Late Byzantium Reconsidered: The Arts of the Palaiologan Era in the Mediterranean, ed. by Andrea Matiello and Maria Alessia Rossi (London: Routledge), pp. 71–84

Underwood, Paul. 1975. ‘Some Problems in Programs and Iconography of Ministry Cycles’, in The Kariye Djami, vol. 4, Studies in the Art of the Kariye Djami, ed. by Paul Underwood (Princeton: Princeton University Press), pp. 297–301

______. 1966. The Kariye Djami, 3 vols (New York: Bollingen Foundation), 3: 149–51

Benjamin West :

Christ Healing the Sick in the Temple, 1817 , Oil on canvas

T'oros Ṙoslin :

The Sick and the Possessed, from the T'oros Roslin Gospels, 1262 , Illuminated manuscript

Unknown artist :

The Healing of the Multitude, 1320s , Mosaic

Multiplying Multitudes

Comparative commentary by Rossitza B. Schroeder

The Gospels are rather laconic when describing the healing of multitudes; they commonly devote only one or two verses to it, unlike the curative miracles that involve specific individuals. This afforded the artists who visualized them more freedom in imagining the setting as well as the various ill people to be incorporated in the crowd.

Both T’oros Roslin and the anonymous Byzantine mosaicist represented the sick in an outdoor setting (as in Matthew 8 and 15), to indicate that Jesus encounters them on the road or to imply that they were separated, if not even ostracized (as was the case with lepers, for example), from the rest of the world.

Unlike his medieval predecessors, Benjamin West, following the specifics of Matthew 21, painted impressive monumental architecture—the forecourt of the Jewish Temple—as the grand backdrop for the healings. Certain details, such as the heavy red curtain in the left corner as well as the two female figures who support trays of sacrificial pigeons on their heads, hint at the ultimate sacrifice of the Son of God. The miracle thus anticipates Christ’s salvific death, aligning healing with salvation.

The indeterminacy of—and variation in—the locations of these healings of ‘multitudes’ allow multiple additional possibilities to be imagined. An area framed by the margins of a physical book in the case of T’oros Roslin, a chapel within the Chora church, and a Philadelphia hospital can all become the ‘sites’ of Christ’s miraculous action. The narratives are thus extended in the direction of the viewers and into their immediate settings.

Christ occupies the central place within both the Byzantine mosaic and West’s painting. In both cases, he is accompanied by his disciples. They are solemn and clustered closely together, more observers than participants in the event. Their presence also provides a commentary on various aspects of Christian living. For example, in West’s painting Christ is flanked by two of his main disciples—St John to his right and St Peter to his left. John is represented as young and thoughtful. The event appears to have stirred up his introverted and contemplative nature. He looks down while gently touching his cheek with his hand in a pensive gesture. The figure of St Peter represents the opposite. He appears robust and agitated as indicated by his slightly asymmetrical facial features and dishevelled hair. Contemplation and action, traditionally understood as two sides of the Christian way of life, are thus epitomized by the portraits of the two apostles.

These three artworks are more than mere recordings of physical cures. Thus, one can argue that the Chora mosaic provides a form of visual exegesis of Christ’s miraculous healings. It functions as a device to aid meditation and presents a particular form of story-telling meant to guide the viewer’s attention from one image to another. It invites associations with other mosaics in close proximity to it, as well as with the rites and rituals which would have happened in the space of the chapel. The icon reflects both the eternal as well as the concrete, time-specific concerns of the Chora monks. Within it, the present is inserted into the venerable past; the church becomes the space where the temporal ‘now’ can be incorporated seamlessly within the timeless ‘always’.

Besides providing opportunities to meditate on the complex and sometimes inextricable relationship between illness and sin, healing and absolution, these images of Christ’s miracles functioned also as an appropriate backdrop for the charitable actions of the institutions where they were shown. Thus Theodore Metochites, the fourteenth-century patron of the Constantinopolitan Chora monastery, insisted that the resident monks should attend to the needy and sick outside the walls of the monastery. In the same vein, Benjamin West wrote that the main subject of his painting was ‘the Redeemer of Mankind extending his aid to the afflicted of all ranks and conditions’ (Morton 1897: 578). The purpose of his painting appears to have been to highlight the altruistic and philanthropic nature of medicine. Christ demonstrates that everyone in our world—irrespective of their age or social status—is a rightful recipient of relief and healing.

The three representations discussed here provide a window into a particular but often, today, neglected understanding of the inalienable connection between body and soul. They offer a holistic vision of medicine as a discipline which attends in equal measure to both physical and spiritual afflictions.

References

Morton, Thomas George. 1897. The History of the Pennsylvania Hospital, 1751–1895 (Philadelphia: Times Printing House)

Ševčenko, Ihor. 1975. ‘Theodore Metochites, the Chora, and the Intellectual Trends of His Time’, in The Kariye Djami, vol. 4, Studies in the Art of the Kariye Djami, ed. by Paul Underwood (Princeton: Princeton University Press), pp. 17–91

Commentaries by Rossitza B. Schroeder