Hebrews 6

The Peril of Falling Away

David Jones

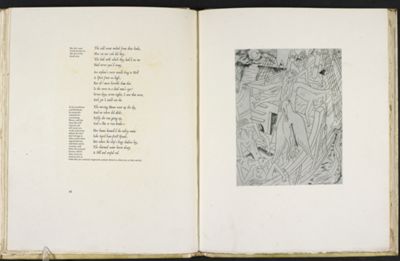

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, 1929, Print, The British Library, London; C.100.k.20., ©️ Trustees of the Estate of David Jones; Photo: ©️ The British Library Board (C.100.k.20., p.17)

‘Things that belong to salvation’

Commentary by Hilary Davies

After the harsh admonition of the opening verses, the author of Hebrews begins to modulate his argument: ‘For God is not unjust; he will not overlook your work and the love you showed for his sake’ (6:10). A supreme example of such divine remembrance is explored in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s masterpiece, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

When David Jones undertook in late 1927 to illustrate this poem, he was already regarded as one of Britain’s foremost watercolourists and wood engravers (Dilworth 2017: 122; Miles & Shiel 1995: 78). But Jones had never attempted copper engraving before; this determined his decision to concentrate on ‘simple incised lines reinforced ... by cross-hatched areas’ (Dilworth 2005: 13). His focus on stark simplicity to suggest rich layers of meaning perfectly mirrors the shimmering language and deceptively ballad-like prosody of Coleridge’s poem. ‘Engraving 5’ depicts the Mariner, albatross slung from his neck. His eyes are dead, pupil-less; his soul is in agony, for whenever he has tried to pray, a travesty falls from his lips, ‘A wicked whisper came, and made | My heart as dry as dust’ (Ancient Mariner, 60). Not only the albatross but he and the whole crew are pierced by the crossbow of his sin.

Yet he leans in Christ-like pose against the mainmast, a part of the boat that was always for Jones redolent of the cross. Alongside slither the water snakes which will be the occasion of his deliverance, ‘A spring of love gushed from my heart, | And I blessed them, unaware’ (ibid: 62). This death-ship is about to become the vessel of his transformation because he is suddenly able to love God’s creation afresh. Although he betrayed the trust of the albatross, thereby showing contempt for ‘all things both great and small’ (ibid: 80), he now ‘seize[s] the hope set before [him]’ (Hebrews 6:18) by ‘the dear God who loveth us’ (Ancient Mariner, 62). In that moment, the string attaching the albatross to his neck in Jones’s engraving seems to slacken, thereby allowing forgiveness to begin, ‘The Albatross fell off, and sank | Like lead into the sea’ (ibid).

References

Dilworth, Thomas. 2017. David Jones: Engraver, Soldier, Painter, Poet (London: Jonathan Cape)

Miles, Jonathan and Derek Shiel. 1995. David Jones, The Maker Unmade (Bridgend: Seren)

Jones, David. 2005. The Ancient Mariner, ed. by Thomas Dilworth (Alton: Enitharmon Press)

Francesco Berretta after Giotto

Navicella, 1628, Oil on canvas, 740 x 990 cm, Fabbrica di San Pietro, Rome; Web Gallery of Art

‘God made a promise’

Commentary by Hilary Davies

The twist that comes in Hebrews 6:16–20 is designed to offer the greatest hope there is—the exact opposite of the apparent rejection we encounter at the beginning. By the gift of himself, God has guaranteed ‘hope, a sure and steadfast anchor of the soul’ (6:19).

From the early fourteenth to the mid-seventeenth century, the last thing that pilgrims to Old St Peter’s in Rome saw as they left the basilica was a vast mosaic designed by Giotto. It was placed above the arcade that formed the entrance and exit to the precinct, known as ‘the Paradise’, and depicted Peter’s attempt to walk towards Christ upon the waters, related in Matthew 14:22–33. The mosaic was almost totally destroyed in the building of the current church, but several copies remain, of which Francesco Berretta’s is the largest and gives the best sense of how impressive the original and its message were.

The scene is dominated by the huge bellying sail of the disciples’ boat running before the wind. There is a feeling of great strain and danger: some of the men clasp their heads in their hands, others pull on the ropes or struggle at the helm. The image captures the very moment when Peter, having trusted Christ enough to get out of the ship to walk towards him, is seized with fear and begins to sink. His back and knees crumple as the element dissolves beneath him; his face is upturned pleadingly; he cries out in horror at the realization that what he set out to do is impossible. Despite having ‘tasted the heavenly gift’ (Hebrews 6:4), this most faithful follower of Christ’s word now doubts the very Word that he has been living by and starts to fall away into the deep. Yet his fingers are about to touch those of Christ: safety, and salvation, are nigh. Even at the moment of Peter’s betrayal, and there will be more, God keeps his promise and rescues his pusillanimous disciple from the tides of infidelity.

Francis West

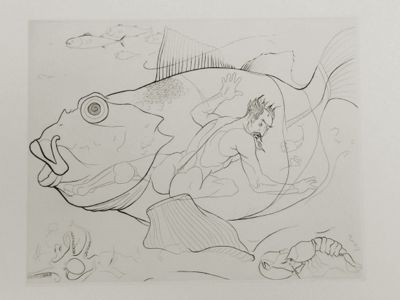

Jonah, 20th century (?), Etching, 222 x 300 mm, Private Collection; Courtesy of Estate of Francis West

Falling Away

Commentary by Hilary Davies

The first verses of Hebrews 6 (1–8) carry a warning that could not be more severe:

it is impossible to restore again to repentance those who have once been enlightened, and have tasted the heavenly gift, … and then have fallen away.

The remarkable Old Testament story of Jonah shows us the terrifying consequences of such a lapse. In the etching Jonah by Francis West, the prophet stares fiercely through the body of the fish in which he is imprisoned down towards the sea floor. It is as if he sees opening beneath him the ever greater depths of the belly of Sheol into which he has been cast by his disobedience to the command of God: he has failed to go to the city of Nineveh, as requested, and denounce the wickedness of its king and citizens.

Here is one who has heard the word of the Lord, and has said no: he flees to Joppa and boards a ship to get as far away from the Lord as he can (Jonah 1:1–3). Now, despite his powerful musculature and mature beard, which should denote strength and experience, he is entombed in unnatural circumstances and surrounded by sea creatures, like the octopus and the lobster, which are ritually unclean (Leviticus 11:10–12).

But his refractoriness is interspersed with expressions of great faith in the promises of his Lord:

I with the voice of thanksgiving will sacrifice to you; what I have vowed I will pay. Deliverance belongs to the Lord. (Jonah 2:8–9)

Jonah has offered himself as a sacrifice by exhorting the sailors to throw him overboard so that they may be saved from the storm. He does return to Nineveh to fulfil his prophetic calling (Jonah 3).

But then, astonishingly, he goes off in a huff when God takes pity on its repentant citizens. Yet again, Jonah has said no to the purposes of his Creator (Jonah 4:1–5). This is a man who seesaws between acceptance and denial: he knows yet he rejects; he falls away yet he persists, teetering constantly ‘on the verge of being cursed’ (Hebrews 6:8). The great fish that immures him is the vacillation of his own mind; the creature’s enormous staring eye becomes the all-encompassing and inescapable eye of God.

David Jones :

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, 1929 , Print

Francesco Berretta after Giotto :

Navicella, 1628 , Oil on canvas

Francis West :

Jonah, 20th century (?) , Etching

‘Hope, a sure and steadfast anchor of the soul’

Comparative commentary by Hilary Davies

Hebrews is a complex exposition of the relationship between the revelations made to Israel and recorded in the Hebrew Bible and the New Covenant embodied by Christ (Carson 1994: 1321). The writer displays great inwardness with Judaic religious practice and the role of the Jewish priesthood in regard to God and the community; he is also steeped in the sacred texts of Judaism, as his references to the Psalms, the Prophets, and the Torah reveal. Yet, the thrust of his theological argument is that Christ has fulfilled the Mosaic Law by himself becoming the high priest: instead of ritual gifts of sacrificed animals, he offers himself as a permanent redemptive sacrifice. The author repeatedly exhorts the participants in the New Covenant not to forget what has been revealed to them nor return to their old ways.

Hebrews 6 lies at the centre of these exhortations, reflecting the dual themes of warning and encouragement. These themes speak to all those who would believe but cannot, or those who struggle to hold true to their faith when faced with adversity or persecution. The language of the letter sounds stark to modern ears, but the psychological reality is only too contemporary: lack or loss of faith leads to loss of hope, which leads to despair, the most terrifying of all fallings away, because it is a falling away from life. For this very reason, God remains always willing ‘not to overlook your work and the love that you showed for his sake in serving the saints’ (Hebrews 6:10). He is not unjust; he offers ‘hope, a sure and steadfast anchor of the soul’ (vv.10, 19).

The three artworks here each provide their own perspective on the balance of hope and despair, despair and hope. Jonah’s lament at being cut off from God is one of the most eloquent in the Hebrew Bible, yet this punishment follows his act of self-immolation to save the lives of others. We sense the paradox of his plight in Francis West’s powerfully writhing figure, his hands pushing against the walls of his fishy prison, the raised eyebrows, his prophet’s hair standing on end. And even when reprieved, he doesn’t learn, but repeatedly asks to die. The gourd that later springs up on the outskirts of Nineveh to protect him, and which then shrivels when the worm attacks it, leaving him exposed to the scorching sun, embodies the dichotomy of the fertile and blasted earth of Hebrews 6:8: if we are faithless to our promise, our ‘end is to be burned over’. We never discover what Jonah’s ultimate fate is to be.

The divine spirit comes to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Mariner, in time-honoured fashion, in the form of a bird, ‘As if it had been a Christian soul, | We hailed it in God’s name’ (Ancient Mariner, 49). Unlike Jonah, the sailor has been at one with God’s creation until he destroys this equilibrium by shooting the albatross. David Jones’s engraving portrays both bird and man strung on the mast, an iconography which clearly points to the crucifixion: the mariner, having ‘shared in the Holy Spirit’, (Hebrews 6:5) now has to endure himself ‘crucifying again the Son of God’ (v.6). Hebrews 6 appears categorical that such a sin carries the gravest of punishments: ‘it is impossible to restore again to repentance those who have once been enlightened’ and have since fallen away (6:4). By blessing the sea-creatures, the mariner is redeemed, but never freed from the penance of having to retell his tale. It is a warning to others never to repeat his mistake, never to reject God.

Peter the rock, first named of the disciples (Matthew 4:18). Peter the chosen witness to the Transfiguration. Peter who insists he will never desert Christ (Mark 9:2). Peter who falls asleep when his Lord needs him most (Mark 14:32–37). Peter who huddles by the fire in the night and denies knowing Jesus at all. This frail person is nevertheless the one of whom Christ says, ‘And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church’ (Matthew 16:18). The yo-yoing description of promise and failure that characterises Hebrews 6 fits Peter’s behaviour perfectly: his weakness is all there in the desperate attitude of the sinking figure reaching out to Christ. But he will go on to bear witness to the risen Lord in such a way as to transfigure for ever the world into which he was born. He does this because he has experienced, body and soul, that, while humankind may prove false, ‘it is impossible that God should prove false, we who have taken refuge … have this hope, a sure and steadfast anchor of the soul’ (Hebrews 6:18–19). This Christ does not fail Peter but holds out his hand to him across the deep.

References

Carson, D.A., et al. (eds). 1994. New Bible Commentary, fourth edn (Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity Press)

Commentaries by Hilary Davies