Ecclesiasticus 3

To Love, Honour, and Obey

Guercino

Christ Appearing to St Teresa, c.1634, Oil on canvas, 298 x 202 cm, Musée Granet d’Aix-en-Provence; ©️ RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Honouring the Father

Commentary by Alysée Le Druillenec

Honour your father by words and deed, that a blessing from him may come upon you. (Sirach 3:8)

Arms crossed over her chest, looking upwards, Teresa of Ávila kneels before the Christ who appears to her and points up to heaven.

Jesus’s gesture establishes a line along which our eye can travel—upwards to the dove representing the Holy Spirit (see Matthew 3:16) and then to God the Father. This line connects the three trinitarian persons, all of whom are looking at Teresa. A second line is the one established by Teresa’s raised eyes, which are focussed directly on the Father, and reciprocate his regard.

In her writings, Teresa draws an analogy between honouring the Father in heaven and observing the Fourth Commandment to honour one’s earthly parents (Exodus 20:12; Deuteronomy 5:16; see Mark 10:19). If we ‘honour [our] father by words and deed’ (Sirach 3:8), then we will also be attentive to our heavenly Father and will ‘have respect for His honour’ (Dalton 1852: 129). In this way a devotee can come to understand herself as God’s child, a ‘partner and co-heir’ with Jesus (see Exodus 20:12; Proverbs 13:22a; Deuteronomy 21:16; Jeremiah 2:7a).

The interpenetration of the celestial and terrestrial spheres is revealed in the virtuous circle between the Trinity and the saintly intercessor. The in-between space in Guercino’s painting can be read as a metaphorical representation of the spiritual place into which we—with Teresa—are invited; a space in which one can ‘stand between this Father and this Son [and] necessarily find the Holy Spirit’ (Teresa, Dalton 1852: 129).

By representing her as a role model for the devotee who must ‘honour the Father’ Guercino’s painting may allude to Teresa’s writings about trinitarian participation (or inhabitation). Guercino depicts how the human soul and the Holy Trinity can become present to each other (Teresa, Sesé 1995: 89–93).

For Teresa, honouring one’s earthly father will result in honouring the Father who is in heaven. And if we honour the Father in heaven, then we ourselves become like his children and heirs, along with Jesus—caught up into an encounter with the Father and the Spirit through the Son.

Following the teaching of Matthew 6, Teresa thus invites the devotee into a prayer that ‘is a cry of trust, in faith, hope and love’ (Teresa, Dalton 1852: 129).

References

Alvarez, Tomás (ed.). 2008. Dictionnaire Sainte Thérèse d’Avila. Son temps, sa vie, son œuvre et la spiritualité carmélitaine (Paris: Cerf), pp. 355–60

Dalton, John (trans.). 1852. Teresa of Ávila: The Way of Perfection, and Conceptions of Divine Love (London: C. Dolman)

Dekoninck, Ralph. 2016. ‘The Mystical Experience—Between Personification and Incarnation: The Idea vitae Teresianae iconibus symbolicis expressa (Antwerp, Jacob Mesens: 1680s)’, in Personification. Embodying Meaning and Emotion, ed. by Walter Melion and Bart Ramakers (Leiden: Brill), pp. 186–207

Druillenec (Le), Alysée. 2021. ‘L’Inhabitation trinitaire chez Thérèse d’Avila, objet d’une théologie en histoire de l’art ?’, Perspective, 2: 151–58

Sesé, Bernard and Carmélites de Clamart (eds). 1995. Œuvres complètes, Thérèse d'Avila, Tome 4, Château intérieur 7, 1, 5–7 (Paris: Cerf), pp. 89–93

Bartolomé Estebán Murillo

The Infant Christ Asleep on the Cross, c.1670, Oil on canvas, 198.8 x 143.5 cm, Sheffield Galleries and Museums Trust; Gift from J. G. Graves, 1935, VIS.73, ©️ Sheffield Museums Trust

Among Us in Great Humility

Commentary by Alysée Le Druillenec

The greater you are, the more you must humble yourself (Sirach 3:18)

Bartolomé Estebán Murillo’s painting reflects the devotional climate of the seventeenth century, when ‘the strange kinship of the Infant Child and the death it heralds’ was promoted by spiritual authors such as Pierre de Bérulle (Le Brun 2020: 44). It found visual expression in the works of seventeenth-century painters such as Hieronimus Wierix, Philippe de Champaigne, and Artemisia Gentileschi (Le Brun 2020: 44). In works such as this, the Son is presented to the viewer in His most humble ‘State’ (Bérulle 1623: 40) and paradoxical greatness.

The fact that the Holy Child lies asleep on a cross immediately brings to mind his future Crucifixion, as does the way his right arm rests on a skull, symbolizing Golgotha (Matthew 27:22; Mark 15:22; Luke 23:33; John 1:17). This painting thus connects two major moments in Christ’s life: his birth (the Mystery of the Incarnation, John 1:14) and his death (the Mystery of the Crucifixion, Philippians 2:6–11). It is symptomatic of a new turn in seventeenth-century Christology and soteriology (see Luke 2:25–38; Hebrews 12:3; Acts 28:28). Indeed, during the Counter-Reformation, theologians insisted on the fact that one must adore, admire, and honour the Father in the Son, reduced to this state of great humility (see John 14:9; 2 Corinthians 5:16), where ‘His mightiness is hidden in his lowerings’ and where ‘his divinity is veiled in our humanity’ (Bérulle 1995: 160).

Furthermore, they argued that meditating on the Child Christ was ‘rejuvenating’, such that one could be ‘internally renewed by the spirit and the grace of His childhood’, which is ‘absolutely necessary to reach the Kingdom of Heaven’ (Parisot 1657: 721).

As an aid to devotion, this painting could guide spectators seeking to see God and to allow His taking to himself the condition of human youthfulness to transform their souls. Indeed, it may have encouraged devotees to aim to become one of ‘the pure in heart [who] shall see God’ (Matthew 5:8; see also Sirach 3:22), with their spiritual eyes and inner senses, the God ‘no one has ever seen’ (John 1:18; see also Sirach 3:23; John 20:21).

Their own ‘lowerings’ might lead to this previously inaccessible summit of glory (see. Sirach 3:18).

References

Benedict XVI. 2008. ‘Saint Paul (10). The Importance of Christology: The Theology of the Cross’, General audience, Wednesday 29 October 2008 (Rome: Libreria Vaticana)

Bérulle (de), Pierre. 1623. Discours de l’estat et des grandeurs de Jésus, par l’Union ineffable de la Divinité avec l’Humanité, Et de la Dépendance & Servitude qui luy est deuë, & à la Tres-Saincte Mere, en suitte de cet Estat admirable (Paris: Antoine Estienne)

Bossuet, Jacques-Bénigne. 1927. ‘Panégyrique Quaesivit subi Dominus’, in Œuvres oratoires de Bossuet 1659–1661, Tome 3, ed. by Joseph Lebarq, Charles Urbain, Eugène Levesque (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer), pp. 643–65

Brun (Le), Jacques. 2020. Le Christ imaginaire au xviie siècle (Paris: Jérôme Million)

Dupuy, M. (ed.). 1995. Œuvres complètes, Pierre de Bérulle, Tome 3, Œuvres de piété (Paris: Oratoire de Jésus / Éd. du Cerf)

Parisot, Joseph. 1657. Explication de la dévotion à la sainte Enfance de Jésus-Christ nostre Seigneur (Paris: Charles David, Aix)

Teske S.J., Roland (trans.), Boniface Ramsey (ed.). 2003. ‘Letter 147’, in Works of Saint Augustine, vol. 2 (New York: New City Press), pp. 323–29, 332

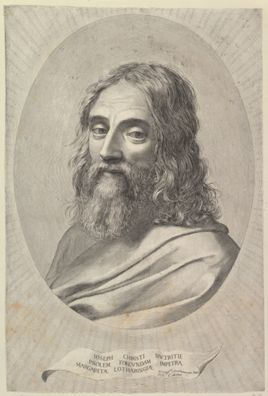

Claude Mellan

Bust of St Joseph in an Oval, 17th century, Engraving, 427 x 287 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1953, 53.601.255, www.metmuseum.org

The Alter-Father

Commentary by Alysée Le Druillenec

For the Lord honoured the father... (Sirach 3:2)

During the Counter-Reformation, the cult of St Joseph evolved significantly. According to contemporary spiritual literature and devotional images, he became the ideal model of prayerful obedience.

Claude Mellan’s engraving of the saint sums up this seventeenth-century josephology very effectively. He elides Joseph’s facial features with those of God the Father by representing him as a bearded man who is markedly similar to God the Father in some of his other engravings, such as Je croy en Dieu le Père tout puissant (c.1615–16), and the frontispiece for his Bible of 1652.

Joseph’s own honouring of God the Father in obedience (Matthew 1:18–24) gives him a unique paternal intimacy with the Son:

[He] possessed [the Christ Child] without any in-between, knew Him with the eyes of the body, carried Him on his arms, lodged Him in his house, fed Him with his sweat, cherished Him as his Son and received from Him ineffable honours. (Jacquinot 2013: 39)

Without any mediator between himself and Christ, Joseph could be seen as ‘an image of God’ (Binet 1866: 53). In this sense, Joseph was seen as the alter-Father who should be honoured by not only his Son, the son of God, but all humankind. Joseph’s likeness to God belongs only to [him]’ and ‘nothing is more similar to the Father, who carries the uncreated Word in his bosom, than Joseph, carrying the incarnate Word in his arms’ (Binet 1866: 53).

Joseph’s representation as like God expresses how the Lord himself ‘communicated his paternity’ to him (Binet 1866: 52), as he did to Abraham (Genesis 17:4; see also Sirach 3:3). In other words, as God communicated fecundity to Mary in the mystery of the Incarnation, he communicated to Joseph His quality of fatherhood—a fatherhood belonging to Joseph by grace not by nature. In turn, the Son offered him his own earthly submission (Léon de Saint-Jean 1665: 514).

During and after the Council of Trent (1545–63), Joseph’s paternal deeds became considered paradigmatic acts of faith on which the beholder must meditate (Coton 1988: 105–08; Pope Francis, 2020). Images of the Holy Family were seen as representations of an earthly Trinity whose chief was Joseph. Paterfamilias par excellence, he became the protector (Sirach 40:27) and the authority figure of both Christ’s nuclear family and the whole Christian community (Barry (de) 1639: 44).

References

Barry (de), Paul. 1646. La dévotion à saint Joseph le plus aymé et le plus aymable de tous les saints après Jésus et Marie (Lyon: Pierre et Claude Rigaud)

Binet, Étienne. 1866 [1639]. Le tableau des divines faveurs accordées à saint Joseph (Paris: Principaux libraires)

Bossuet, Jacques-Bénigne. 1927. ‘Panégyrique Quaesivit subi Dominus’, in Œuvres oratoires de Bossuet 1659–1661, Tome 3, ed. by Joseph Lebarq, Charles Urbain, Eugène Levesque (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer), pp. 643–65

Coton, Pierre. 1933 [1608]. Intérieure occupation d’une âme dévote. Nouvelle édition (Paris: Pierre Tequi)

Jacquinot, Jean. 2013 [1645]. Les Grandeurs de saint Joseph. « Allez à Joseph » Génèse 41,55 (Auriac: Saint Jean Librairie Chrétienne)

Léon de Saint-Jean. 1665. La couronne des saints, Tome 1 (Paris, C. Josse), pp. 514–15

Pope Francis. 2020. ‘Patris corde. Apostolic Letter of the Holy Father Francis on the 150th Anniversary of the Proclamation of Saint Joseph as Patron of the Universal Church, 8 December 2020’ (Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana)

Guercino :

Christ Appearing to St Teresa, c.1634 , Oil on canvas

Bartolomé Estebán Murillo :

The Infant Christ Asleep on the Cross, c.1670 , Oil on canvas

Claude Mellan :

Bust of St Joseph in an Oval, 17th century , Engraving

The Wisdom to Honour, Obey, and Love

Comparative commentary by Alysée Le Druillenec

Written by Ben Sira, Ecclesiasticus or Sirach is one of the five Wisdom books. In Roman Catholic and Orthodox Christianity, following the Septuagint (LXX), it appears after Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Wisdom of Solomon whereas in Jewish and Protestant traditions it is apocryphal but still viewed as containing wise teaching. This book is the fruit of a long and deep meditation on Wisdom (51:13–30), which Ben Sira shares with the reader (37:27–28; 41:14).

Sirach 3 addresses duties towards parents as a practice of Wisdom and is a direct commentary on the Fourth Commandment (Exodus 20:12). This Commandment is unique, offering God’s benediction in return for keeping it: ‘Honor your father and your mother, so that you may live long in the land the LORD your God is giving you’. Sirach 3’s focus on the interchangeability between earthly parental figures and God the Father (vv.2–6, 12–14) mirrors the commandment’s unique structure. The chapter shows that honouring one’s parents results in blessings: the grace of great fulfilment of one’s relationship with God (vv.12–13) as one grows in humility and wisdom (vv.7, 17–29).

The artworks selected for this exhibition are both performative and instructive in relation to Sirach 3. They are performative because they show devotees what they must aim for. They are injunctive because, as devotional images, they guide beholders in meditation with a representation that can support their prayers. Therefore, by carrying these images in their mind and heart while praying, devotees are already carrying Christ and, therefore, honouring the Father.

Guercino’s Teresa of Ávila before the Holy Trinity gives an almost literal interpretation of what it is to receive the gift of the revelation of the Holy Trinity. Teresa wears her habit, is barefoot and kneeling with arms crossed over her chest, and looks upward. These are all signs of the holy conduct that has resulted from a long meditational path honouring the Father and seeking to participate in Him.

However, from her point of view, she can see only Jesus and (maybe) the Dove of the Spirit. She cannot see the Father, who is concealed by a thick cloud. Guercino thus accurately shows how crucial her specific relationship with Christ is to ‘considering’ the Three Persons (Teresa, Sesé 1995: 397). Moreover, the trinitarian mystery is revealed to the viewer at the very moment when Teresa is about to understand it herself. Christ’s index finger is thus as deictic (i.e. offering a situated showing; a showing-in-context) as it is didactic. It emphasizes not general truths about the triune God but the active relation of the Trinity both to Teresa and also, potentially, to the devotee who gazes at the painting.

Bartolomé Estebán Murillo’s Infant Child Sleeping on the Cross communicates what seeing God and perceiving the Mysteries of Incarnation and Crucifixion with one’s higher (‘intellectual’) vision might be like (Augustine, ‘Letter 147’: 334). It offers the devotee a way to understand by way both of one’s physical and one’s spiritual senses that ‘only the Son’ has made God ‘known’ (John 1:18). Furthermore, by representing a sleeping Christ, it invites the devotee to imitate that intimate confidence and love which unites Him to his Father (see Matthew 8:22–27) during His last moment on the Cross (Luke 23:46; see also Psalm 31:6). Ultimately, this painting contributes to a christological discourse expressing how the Fourth Commandment is intrinsically linked to salvation: to honour the Incarnate Word in the Child Christ, is to honour the Father who saves humanity by allowing His Son to be sacrificed.

Claude Mellan’s Portrait of Saint Joseph looking like God the Father encourages devotees to experience the imprint of God’s seal by bearing God’s image in their minds, by way of a meditation on Joseph. They are invited to reflect on how Joseph’s paradigmatic humanity and great wisdom mirror the Father who ‘created [humankind] in his own image’ (Genesis 1:27). This engraving can be read as offering an interpretation of the value of honouring one’s father (as in Sirach 3) in terms of the benediction received by believers within the Christian Church when honouring this saintly father. Indeed, because of his great wisdom, Joseph received the grace to be Mary’s spouse, who is in turn the symbol of the Church as Christ’s Spouse. He could also fulfil the role the Christ’s earthly father, to whom God communicated His own paternal grace.

In fine, this exhibition shows how crucial images are in the practice of Ecclesiasticus’s (Sirach’s) wisdom. Devotees who incline themselves towards God (42:15; 43:33; 50:21) must, to this end, seek wisdom in their earthly lives by forging their souls’ disposition (habitus) in ‘words and deed’ (v.8), and by allowing themselves to ‘[be] acted upon’ by the Holy Spirit (Aquinas Summa Theologiae 2–1, 63–3.2).

References

Certeau (de), Michel. 1982. La Fable mystique. xvie-xviie siècle (Paris: Gallimard)

Mâle, Émile. 1932. L’art religieux après le concile de Trente. Étude sur l’iconographie de la fin du xvie siècle, du xviie, du xviiie siècle. Italie – France-Espagne – Flandres (Paris: Armand Colin)

Pelikan, Jaroslav. 1973–90. The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

Sales (de). François. 1845. Œuvres, 6: Les Vrays Entretiens spirituels. Dix-neufvieme entretien. Sur les vertus de saint Joseph (Annecy: J. Nierat), pp. 203–42

Sesé, Bernard and Carmélites de Clamart (eds). 1995. Œuvres complètes, Thérèse d'Avila, Tome 4, Château intérieur 7, 1, 5–7 (Paris: Cerf), pp. 89–93

Teske S.J., Roland (trans.), Boniface Ramsey (ed.). 2003. Works of Saint Augustine, vol. 2 (New York: New City Press), pp. 323–29, 332

Commentaries by Alysée Le Druillenec